Resilience in Positive Psychology: How to Bounce Back

Resilience in positive psychology refers to the ability to cope with whatever life throws at you.

Resilience in positive psychology refers to the ability to cope with whatever life throws at you.

Some people are knocked down by challenges, but they return as a stronger person more steadfast than before.

We call these people resilient.

A resilient person works through challenges by using personal resources, strengths, and other positive capacities of psychological capital like hope, optimism, and self-efficacy.

Overcoming a crisis via resiliency is often described as “bouncing back” to a normal state of functioning. Being resilient is also positively associated with happiness.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Resilience Exercises for free. These engaging, science-based exercises will help you to effectively deal with difficult circumstances and give you the tools to improve the resilience of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- Let’s Start at the Beginning: Resilience

- Environments for Growth

- How Do I Become More Resilient?

- Developing a Mindset That Fosters Success

- Identify and Leverage Your Strengths

- Learn to Perceive Obstacles as Challenges Rather Than Hindrances

- Focus on Progress, not Goals

- Practice Your ABC’s

- A Take-Home Message

- References

Let’s Start at the Beginning: Resilience

Relationships play a vital role in building the resilience of an individual. This starts at a young age when we are heavily influenced by our guardians and parents. More resilient children tend to be raised with an authoritative parenting style, rather than authoritarian or passive parenting styles.

The authoritative parenting style displays the qualities of warmth and affection that also provide structure and support to the child. Baumrinds’ (1971, 2013) theory of parenting styles highlights why authoritative parenting is the ideal approach to raising a well rounded, independent, self-reliant, and self-controlled individual.

Opposing this is the authoritarian parenting style, which can result in rebellious or dependent children who experience frequent distrust and thus, tend to be withdrawn from others.

Lopez and Snyder (2009) explain several protective factors for psychological resilience, concluding that parenting style is just one of many factors affecting resilience.

Lopez and Synder also consider parental educational level, socio-economic status and home environment (organized vs. disorganized) as strong influences in the development of a child’s psychological resilience.

Many researchers similar conclusions about Baumrinds’ categorization of parenting styles. The type of relationship, as well as the type of person in the relationship, play big roles in the development of resilience. When positive relationships occur, well-adjusted and rule-abiding behaviors are valued; these influence strong positive effects on resilience levels.

Characteristics of resilience include cognitive skills, personality differences, problem-solving ability, self-regulation, and adaptability to stress. In early relationships and supportive environments, children can develop tools that subconsciously develop their psychological resilience and these aforementioned skills.

Lopez and Snyder mention these key protective individual factors as:

- Positive self-image;

- Problem-solving skills;

- Self-regulation;

- Adaptability;

- Faith/understanding the meaning and one’s purpose;

- Positive outlook;

- Skills and talents that are valued by self and community;

- General acceptance by others.

Environments for Growth

Factors such as public safety, availability to health care, access to green space, etc., all impact the development of an individual and a community’s resilience. The greater the social care and holistic environments, the more likely people will be exposed to the support structures that can help them when life “gets hard.”

Education is one major factor to consider. Schools could be epicentres of developing resilience, as well as safe spaces to practice and develop these skills. Prosocial organizations such as sports teams or clubs can also be hotspots of resilience-training. These environments enable individuals to develop a positive self-image, believe in their strength, and find the purpose amidst change.

A core part of the positive education movement is creating prosocial organizations and effective schools.

For a great example of how to implement resilience in your own environment, check out the Penn Resiliency Program that links wellbeing and resilience together. Penn designs the program to fit the individual needs, goals, and culture of organizations.

Researcher Dr. Karen Reivich offers a pool of resources in this program. Essentially, every program, workspace, school, etc., can benefit from creating a culture of resilience.

How Do I Become More Resilient?

Even if the environment you grew up wasn’t ideal to develop resilience, it’s never too late. Being resilient is not a personality trait: it is a dynamic learning process.

A major point in learning resilience is to take a perspective on things. In moments of stress, it might be useful to place your individual situation into a bigger context and grasp on its real severity, or the lack thereof.

For example, one visualization technique that can build resilience is to think of a recent challenge or “crisis” in your personal life. Imagine the place you currently exist and slowly zoom out of yourself. Slowly zoom out of the building you’re in, out of the place, out of the state, country and even continent. Then zoom out further—all the way through the ozone layer—until you reach the moon and you can see the whole earth.

Now think about your problem again: how big is it really? What does it look like from outer space?

It is not simple to “change our thoughts,” but it is often a key first step. Sometimes we need to zoom out, in order to recognize that in the larger scheme of things, maybe we are still okay. Maybe we even learned something from an uncomfortable experience and depended on the support of others.

Sometimes, situations will remain messy and difficult. Zooming out is not a “cure-all.”

But overall, people who are resilient might exhibit a positive attitude that guides them through the obstacle. They shift the label of failure of something negative to something helpful instead. With feedback and motivation, we can each work to get better and “fail forward.”

Getting in touch with other people, helping them, and establishing positivity are important steps in learning resilience. In Harvard’s Positive Psychology 1504 course, professor Tal Ben-Shahar goes in-depth on the subject of resilience in positive psychology.

Our own Hugo Alberts (Ph.D.) presents an exemplary course in Realizing Resilience. This masterclass not only teaches you resilience but will enable you to train others in mastering resilience. The course includes workbooks, exercises, presentations, videos, and much more, and to top it off, you will also earn a certificate of completion once finished with this intense and in-depth course.

All in all, attaining resilience is not simple, but it gets easier with practice. So how do we encourage personal mindsets that influence our daily lives for the better?

Developing a Mindset That Fosters Success

Having experienced an explosion in personal development, success coaching, and lifestyle engineering, today’s world has never been hungrier for the glory of goal achievement.

Whether these goals stem from desires for fitness, entrepreneurship or some other domain, they all have one thing in common: a road paved with uncertainty, sacrifice, and setbacks. As such, it is key that you learn to foster a sense of resilience within yourself to ensure you overcome these setbacks to aid your rise to greatness.

Fortunately, given the abundance of empirical evidence, the methods for doing so have never been clearer.

Detailed below are a series of tools designed to help you cultivate resilience and in doing so prepare you for the road ahead.

Identify and Leverage Your Strengths

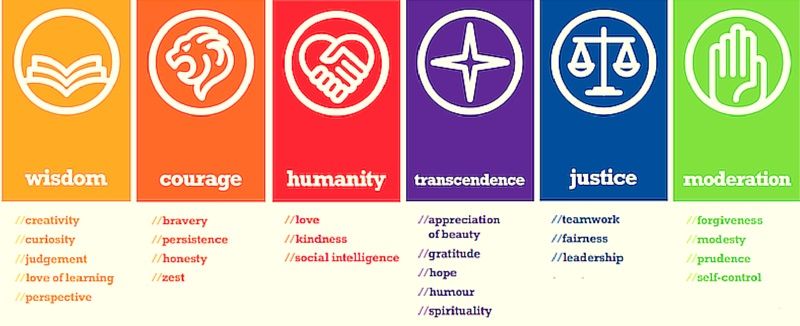

Using your character strengths is a good way to experience your competence.

However, a lot of people don’t know what their strengths are. Something that you are good at comes easily to you, which is why you often take it for granted and don’t recognize it as a major strength.

Learn more about character strengths and take the VIA test for instance to find your strengths. It can also be helpful to ask people who know you well what they think you are good at. While you are at it, ask yourself as well!

Several strengths are associated with happiness, which in turn is a helpful state of mind to become more resilient. Science shows that consciously embracing moments of daily life and being fully present (mindfulness) leads to increased happiness.

“The good life is using your signature strengths every day to produce authentic happiness and abundant gratification.”

Martin Seligman

When times are tough, it’s easy to lose hope and optimism. That’s why we need to know our strengths, especially when life gets tough.

Knowing our strengths helps with greater vitality and motivation, a clearer sense of direction, higher self-confidence, productivity and a higher probability of goal attainment (Clifton & Anderson, 2001-2; Hodges & Clifton, 2004; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Many of us are unaware of what your strengths actually are. To find them, you could ask a close friend or family member to observe you closely for a day or two, or just review what they do know about you. When do you seem most engaged and energized? Why? This process can help identify your strengths.

Maybe write them down somewhere, or keep a tiny note in your pocket, to remind you of them.

You might also try to notice what you do uniquely, with this request feedback from other people. Maybe make it an exchange at work or a dinner gathering: have a list of strengths available for reference, and everyone chooses one strength to describe each coworker, friend, etc., at said event.

Strengths serve us well in times of darkness, as well as times of light. It’s time we start knowing our own and valuing them.

‘Mental toughness is the secret to success’ – BBC Ideas

Learn to Perceive Obstacles as Challenges Rather Than Hindrances

According to the challenge-hindrance stressor framework researched by Cavenaugh et al. (2000), people who view problems with curiosity are more likely to solve the issue and move forward, rather than be defeated by the issue itself.

Why? Because when confronted with a problem, many people view it as an attack on themselves, or as a roadblock that prevents them from a goal.

This victim mentality hinders their progress, and thus weakens their sense of resilience. For example, upon receiving criticism by their boss, a victim may talk back to their boss in anger, deny or excuse the outcome of their work, or even complain about their boss to their colleagues.

Embodying this type of mindset sets people up for failure, which also means additional challenges may, indeed, break a person rather than fuel them forward. Consider this quote:

Challenges are what make life interesting; overcoming them is what makes life meaningful.

Joshua J. Marine

People with a challenge perspective view the problem as an opportunity for growth and as a chance to improve themselves. Unlike a hindrance perspective, a challenge perspective allows people to see their problem as something that has happened “for you” rather than to you.

In some cases, the challenges themselves—especially with hindsight—are actually what provided people with meaning and the passion to persevere. This victor mentality encourages growth, which creates a positive feedback cycle by boosting resilience.

Referring to the above example regarding feedback from a boss, a victor may attempt to understand why the quality of work was not acceptable, request further feedback on how to improve, and maybe even seek advice from colleagues.

In turn, this humility might lead to admiration among staff, and a person who grows into leadership roles since they were willing to adopt a growth-mindset as someone learning along the way.

To summarize, when we acknowledge an obstacle, identify areas for personal improvement, and know our strengths, we position ourselves for meaning and success.

Focus on Progress, not Goals

The following quote aptly summarizes why this may be:

“Progress is not inevitable. It’s up to us to create it.”

Michael Bloomberg

For example, in this APA study, when people report their progress publicly or even physically record it, they are more likely to continue towards their goals.

Digital advancements of our century provide us with the ability to share our journeys on a global scale. Caution is needed with this however, since posting our progress makes us apt to compare our goals and achievements with others.

When people compare themselves negatively with others, they are likely to feel discouraged and doubtful. At that point, all it takes is a minor setback to send you plummeting back to square one. If tracking and sharing progress, it is important to resist the natural urge to compare your goals with others. Try to resist this.

Instead, this APA study shows that acknowledging your progress, no matter how small, sends dollops of dopamine to your brain, thus rewarding yourself for your actions. This reinforces further action so when setbacks arise, we are much more likely to move past them.

In a sense, your sense of resilience thrives on progress. So remind yourself of the strides you’ve made, what fuels you forward, and how you’ve embraced challenges along the way.

“I don’t measure a man’s success by how high he climbs but how high he bounces when he hits bottom.”

George S. Patton Jr.

Practice Your ABC’s

Described by Seligman and addressed in detail in Reivich and Shatté, the ABCDE model allows people to deconstruct a specific “problem” and understand how their “beliefs about what happened” caused them to feel a certain way, not the event itself.

This creates a greater level of awareness about our own reactions, so we can work to have the skillsets needed for a more healthy response to adversity.

The model is composed of 5 steps:

- Adversity;

- Beliefs;

- Consequences;

- Disputation;

- Energization.

These steps help build resilience by recognizing unfavorable thought patterns, finding the true reason behind the emotions, recognizing the negative impact of these emotions, and learning to challenge them.

A Take-Home Message

What if every time we analyzed a problem, we took less fault personally, and instead, adopted a lens that promoted growth and commitment to our goals?

By understanding the problem, our beliefs about the problem, the consequences of those beliefs, and the discrepancy between our believes and the problem itself, we are likely to feel energized and ready to embrace the next challenge more openly.

What are your thoughts after reading this article regarding resilience? Please feel free to leave a comment below. We want to leave you with the following quote:

“Life doesn’t get easier or more forgiving, we get stronger and more resilient.”

Dr. Steve Maraboli

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Resilience Exercises for free.

- Baumrind, D. (1971). Current Patterns Of Parental Authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(1), 1-103.

- Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, A. W. Harrist, R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, A. W. Harrist (Eds.) Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11-34). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., and Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An Empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers, Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 65-74.

- Clifton, D. O., & Anderson, E. C. (2001). StrengthsQuest. Washington: The Gallup Organisation.

- Harkin, B., Webb, T. L., Chang, B. P. I., Prestwich, A., Conner, M., Kellar, I., Benn, Y. & Sheeran, P. (2016). Does Monitoring Goal Progress Promote Goal Attainment? A Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 142 (2), 198-229.

- Hodges, T. D., & Clifton, D. O. (2004). Strengths-based development in practice. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 256-268). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Lopez, S. J., & Snyder, C. R. (Eds.). (2009). The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Thank you for sharing such an informative article on education for emotional resilience. In today’s world, it is becoming increasingly important for schools to focus on developing emotional resilience in students, and this article provides valuable insights on how to achieve this.