What Is Self-Efficacy Theory? (Incl. 8 Examples & Scales)

You’ve no doubt heard of self-efficacy before, but it might not mean what you think it means.

You’ve no doubt heard of self-efficacy before, but it might not mean what you think it means.

Self-efficacy is not self-image, self-worth, or any other similar construct.

It is often assigned the same meaning as variables such as these, along with confidence, self-esteem, or optimism; however, it has a slightly different definition than any of these related concepts.

Read on to learn about self-efficacy and what sets it apart from the other “self” constructs.

Self-compassion can help foster self-efficacy. Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will not only help you show more compassion and kindness to yourself but will also give you the tools to help increase the self-compassion of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

What Is the Meaning of Self-Efficacy? A Definition

Self-efficacy is the belief we have in our own abilities, specifically our ability to meet the challenges ahead of us and complete a task successfully (Akhtar, 2008). General self-efficacy refers to our overall belief in our ability to succeed, but there are many more specific forms of self-efficacy as well (e.g., academic, parenting, sports).

Although self-efficacy is related to our sense of self-worth or value as a human being, there is at least one important distinction.

Self-efficacy vs. self-esteem

Self-esteem is conceptualized as a sort of general or overall feeling of one’s worth or value (Neill, 2005). While self-esteem is focused more on “being” (e.g., feeling that you are perfectly acceptable as you are), self-efficacy is more focused on “doing” (e.g., feeling that you are up to a challenge).

High self-worth can definitely improve one’s sense of self-efficacy, just as high self-efficacy can contribute to one’s sense of overall value or worth, but the two stand as separate constructs.

Self-efficacy and self-regulation

Since self-efficacy is related to the concept of self-control and the ability to modulate your behavior to reach your goals, it can sometimes be confused with self-regulation. They are related, but still separate concepts.

Self-regulation refers to an individual’s “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are systematically designed to affect one’s learning” (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007), while self-efficacy is a concept more closely related to an individual’s perceived abilities.

In other words, self-regulation is more of a strategy for achieving one’s goals, especially in relation to learning, while self-efficacy is the belief that he or she can succeed.

The two can be simultaneously developed—particularly through modeling—but they remain distinct constructs (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007).

Self-efficacy and motivation

Similarly, although self-efficacy and motivation are deeply entwined, they are also two separate constructs. Self-efficacy is based on an individual’s belief in their own capacity to achieve, while motivation is based on the individual’s desire to achieve. Those with high self-efficacy often have high motivation and vice versa, but it is not a foregone conclusion.

Still, it is true that when an individual gains or maintains self-efficacy through the experience of success—however small—they generally get a boost in motivation to continue learning and making progress (Mayer, 2010).

The relationship can also work in the other direction to create a sort of success cycle; when an individual is highly motivated to learn and succeed, they are more likely to achieve their goals, giving them an experience that contributes to their overall self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy and resilience

While experiences of success certainly make up a large portion of self-efficacy development, there is also room for failure.

Those with a high level of self-efficacy are not only more likely to succeed, but they are also more likely to bounce back and recover from failure.

This is the ability at the heart of resilience, and it is greatly impacted by self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy and confidence

Finally, self-efficacy is also positively related to confidence, but they are not the same thing; in the words of Albert Bandura:

“Confidence is a nondescript term that refers to strength of belief but does not necessarily specify what the certainty is about… Perceived self-efficacy refers to belief in one’s agentive capabilities, that one can produce given levels of attainment”

(1997, p. 382).

Just as with self-esteem and motivation, self-efficacy and confidence can work in a positive cycle: the more confident a person is in his abilities, the more likely he is to succeed, which provides him with experiences to develop his self-efficacy.

This high self-efficacy, in turn, gives him more confidence in himself, and round it goes.

5 Examples of High Self-Efficacy

It’s relatively easy to spot because those with high self-efficacy tend to be those who achieve, accomplish, and succeed more often than others.

High self-efficacy can manifest as one or more of the following traits and behaviors, among others:

- A student who is not particularly gifted in a certain subject but believes in her own ability to learn it well;

- A man who has had bad luck with relationships so far, but retains a positive outlook on his ability to connect with his upcoming date;

- An expectant mother who is nervous about caring for a new baby, but believes that she has what it takes to succeed, no matter how difficult or scary it is;

- A new graduate who takes a high-profile, high-status job that she has never done before, but that she feels she can succeed in;

- An entrepreneur who pours his heart and soul into establishing his business, but quickly moves on to his next great idea when his business is hit with an insurmountable and unexpected challenge.

There are many more specific examples of high self-efficacy; all you need to do to find them is look around! Surely you know at least a few people with a solid sense of self-efficacy; observe their attitude and their behavior when they meet with challenges, and you will get a real-life example of high self-efficacy in action.

Why self-efficacy matters – Mamie Morrow

Self-Efficacy Theory in Psychology

The term “self-efficacy” is not used nearly as often in pop culture as self-esteem, confidence, self-worth, etc., but it is a well-known concept in psychology.

Albert Bandura and his model

The psychological theory of self-efficacy grew out of the research of Albert Bandura. He noticed that there was a mechanism that played a huge role in people’s lives that, up to that point, hadn’t really been defined or systematically observed. This mechanism was the belief that people have in their ability to influence the events of their own lives.

Bandura proposed that perceived self-efficacy influences what coping behavior is initiated when an individual is met with stress and challenges, along with determining how much effort will be expended to reach one’s goals and for how long those goals will be pursued (1999).

He posited that self-efficacy is a self-sustaining trait; when a person is driven to work through their problems on their own terms, they gain positive experiences that in turn boost their self-efficacy even more.

Bandura also identified four sources of self-efficacy, but we’ll get to those later.

Locus of control explained

To put self-efficacy in other terms, you might say that those with high self-efficacy have an internal locus of control.

The locus of control refers to where you believe the power to alter your life events resides: within you (internal locus of control) or outside of you (external locus of control).

If you immediately have thoughts like, “I only failed because the teacher graded unfairly—I couldn’t do anything to improve my score” or “She left me because she’s cold-hearted and difficult to live with, and I’m not,” you likely have an external locus of control. That means that you do not have a solid sense of belief in your own abilities.

In juxtaposition to the external locus of control is the internal locus of control, in which an individual is quick to admit her own mistakes and failures, and is willing to take the credit and blame whenever it is due to her.

Self-efficacy and an internal locus of control often go hand-in-hand, but too far in either direction can be problematic; those who blame themselves for everything are not likely to be healthy and happy in their lives, while those who don’t blame themselves for anything are likely not completely in touch with reality and may have trouble relating to and connecting with others.

Social Cognitive Theory and self-efficacy

The Social Cognitive Theory is also based on the work of Albert Bandura and incorporates the idea of self-efficacy.

This theory posits that effective learning happens when an individual is in a social context and able to engage in both dynamic and reciprocal interactions between the person, the environment, and the behavior (LaMorte, 2016). It is the only theory of its kind with this emphasis on the relevance of the social context and the importance of maintenance behavior in addition to initiating behavior.

SCT is based on six constructs:

- Reciprocal Determinism: the dynamic interaction of person and behavior;

- Behavioral Capability: the individual’s actual ability to perform the appropriate behavior;

- Observational Learning: learning a new skill or piece of knowledge by observing others (and potentially modeling them as well);

- Reinforcements: the external responses to the individual’s behavior that either encourage or discourage the behavior;

- Expectations: the anticipated consequences of behavior;

- Self-efficacy: the person’s confidence in his or her ability to perform a behavior (LaMorte, 2016).

The theory considers many separate, unique contextual variables when predicting or explaining a person’s behavior, giving it a broad range of potential applications including health, local environment, and the local community. The ultimate goal is to:

“… explain how people regulate their behavior through control and reinforcement to achieve goal-directed behavior that can be mastered over time”

(LaMorte, 2016).

We explore this further in The Science of Self-Acceptance Masterclass©.

Can We Test and Survey Self-Efficacy?

Self-efficacy can indeed be measured.

It is prone to the same sorts of issues as all self-report measures of a somewhat abstract construct, but there are still several methodologically sound ways to go about it.

Some researchers suggest making your scale specific to the type of self-efficacy you want to study; for example, if you are interested in academic self-efficacy, ask about academic pursuits and confidence.

There are some scales available for measuring specific types of self-efficacy, but it is also possible to (carefully!) adapt the general scales to better narrow in on your construct of interest.

Measuring self-efficacy with scales and questionnaires (PDF)

There are several scales and questionnaires you can use to measure general self-efficacy. Three of the most popular are described below.

General/Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)

The General Self-Efficacy Scale may be the most popular self-efficacy scale. It has been in use since 1995 and has been cited in hundreds of articles. It was developed by researchers Schwarzer and Jerusalem, two leading experts in self-efficacy.

The scale consists of 10 items rated on a scale from 1 (Not true at all) to 4 (Exactly true). These items are as follows:

- I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough;

- If someone opposes me, I can find the means and ways to get what I want;

- It is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals;

- I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events;

- Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations;

- I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort;

- I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities;

- When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions;

- If I am in trouble, I can usually think of a solution;

- I can usually handle whatever comes my way.

The score is calculated by adding up the response to each item. The total will be between 10 and 40, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy.

The scale has proven to be reliable and valid in multiple contexts and cultures.

To use this scale, click here.

New General Self-Efficacy Scale (NGSE)

Another useful self-efficacy scale was developed by Chen, Gully, and Eden in 2001. This scale also provides a measure of self-efficacy and improves on the original 17-item General Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Sherer and colleagues in 1982.

It is composed of only 8 items, rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These items are:

- I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I have set for myself;

- When facing difficult tasks, I am certain that I will accomplish them;

- In general, I think that I can obtain outcomes that are important to me;

- I believe I can succeed at most any endeavor to which I set my mind;

- I will be able to successfully overcome many challenges;

- I am confident that I can perform effectively on many different tasks;

- Compared to other people, I can do most tasks very well;

- Even when things are tough, I can perform quite well.

Scores are calculated by taking the average of all 8 responses, which will range from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy.

For more information on this scale, see the original article in which it was developed (Chen, Gully, & Eden, 2001).

Self-Efficacy Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed in 2015 by Research Collaboration, an organization attached to the University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning that aims to improve education for students and professional development for educators.

It consists of 13 items rated on a scale from 1 (Not very like me) to 5 (Very like me). It was created with students and teachers in mind, so it is focused on learning self-efficacy in particular (although it can be modified to fit with another group of young people).

It measures self-efficacy as a two-component construct, made up of:

- Belief that ability can grow with effort;

- Belief in that ability to meet specific goals and/or expectations.

The 13 items are:

- I can learn what is being taught in class this year;

- I can figure out anything if I try hard enough;

- If I practiced every day, I could develop just about any skill;

- Once I’ve decided to accomplish something that’s important to me, I keep trying to accomplish it, even if it is harder than I thought;

- I am confident that I will achieve the goals that I set for myself;

- When I’m struggling to accomplish something difficult, I focus on my progress instead of feeling discouraged;

- I will succeed in whatever career path I choose;

- I will succeed in whatever college major I choose;

- I believe hard work pays off;

- My ability grows with effort;

- I believe that the brain can be developed like a muscle;

- I think that no matter who you are, you can significantly change your level of talent;

- I can change my basic level of ability considerably.

The score is produced on a 0-100 scale for ease of interpretation, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. The results of this scale have proven to be reliable for middle and high school students, suggesting that it is a good option for measuring self-efficacy (Gaumer Erickson, Soukop, Noonan, & McGurn, 2016).

For more information on this scale, click here.

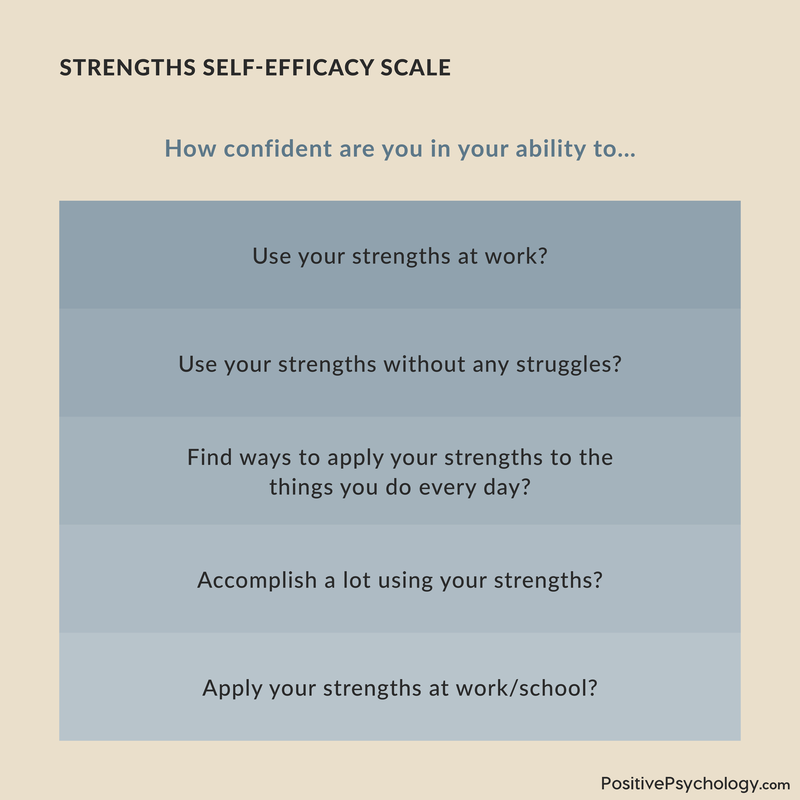

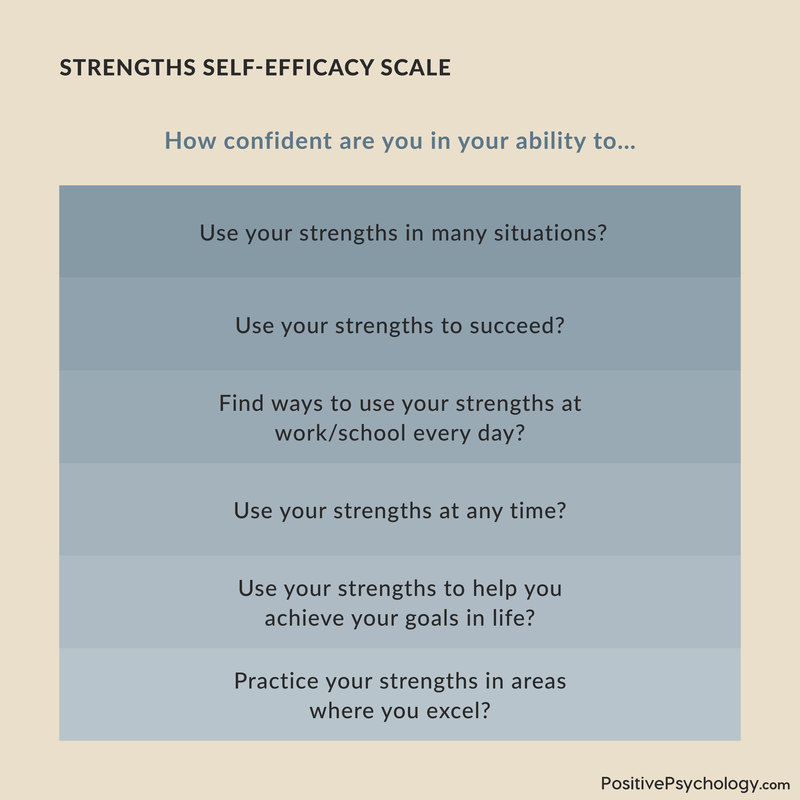

Everybody has strengths. However, not everyone is aware of them, let alone confident enough to use them.

The purpose of the strengths self-efficacy scale is to assess the extent to which you apply your strengths already, and where you can become more confident in your strength use (Tsai et al., 2014).

Using strengths, individually or accompanied by the feeling of self-efficacy, has a positive influence on psychological wellbeing and happiness (Proctor et al., 2011). Many strength interventions are targeted to increase strength awareness, development, and use to help you live more in tune with your strengths.

Research and Studies on the Concept

Accordingly, there is tons of research on the subject, including what it is, how it relates to similar constructs, how it can be improved, and how it impacts people in various contexts.

How to improve self-efficacy beliefs and expectations

According to Bandura, there are four main sources of self-efficacy beliefs:

- Mastery experiences;

- Vicarious experiences;

- Verbal persuasion;

- Emotional and physiological states (Akhtar, 2008).

Mastery experiences refer to the experiences we gain when we take on a new challenge and succeed. The best way to learn a skill or improve our performance by practice; part of the reason this works so well is that we are teaching ourselves that we are capable of acquiring new skills.

Vicarious experience is—quite simply—having a role model to observe and emulate. When we have positive role models who display a healthy level of self-efficacy, we are likely to absorb some of those positive beliefs about the self.

Vicarious experiences can come from a wide range of sources, including parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, older siblings, teachers, and administrative staff, coaches, mentors, and counselors.

The verbal persuasion factor describes the positive impact that our words can have on someone’s self-efficacy; telling a child that she is capable and face any challenge ahead of her can encourage and motivate her, as well as adding to her growing belief in her own ability to succeed.

Finally, emotional and physiological states refer to the importance of context and overall health and wellbeing in the development and maintenance of self-efficacy. It’s difficult to have a healthy level of wellbeing when you are struggling with anxiety or depression, or battling a serious health condition—it’s not impossible, of course, but it is certainly much easier to boost your self-efficacy when you’re healthy and well!

Paying attention to your own mental state and emotional wellbeing (or that of your child’s) is a vital piece of the self-efficacy puzzle.

Another influential self-efficacy researcher, James Maddux, suggested that there may be a fifth main source of self-efficacy: imaginal experiences, or visualization. Exercises that allow you to imagine your future success in detail help you to build the belief that succeeding is indeed possible.

When overcoming the challenge in front of you and meeting your goals feels so real you can taste it (yes, even taste can be apart of such visualization!), it’s hard not to feel empowered and capable.

To enhance your self-efficacy or that of a child in your life, you should focus on ensuring that you have the opportunities you need to master difficult skills and complete challenging tasks, finding positive role models, listening to the encouraging and motivating people in your life, and taking care of your mental health.

Although the impact of visualization is not as well-established as the other four sources, it can’t hurt to give it a try! So, we know those five factors are vital in the development and sustaining of self-efficacy, but how can they be applied, and what impact do they have in different contexts? Read on to find out.

Self-efficacy in learning and education

Self-efficacy has probably been most studied within the context of the classroom. There is a good reason for this, as self-efficacy is like many other traits and skills—best developed early to reap the full benefits.

Much attention has been paid to how teachers can most effectively boost their students’ self-efficacy and help them to learn, work, play, and communicate with others in a healthy and productive way.

It turns out that one of the best ways to enhance self-efficacy in those you teach or lead is to first ensure that you have a healthy sense of self-efficacy!

Developing Teacher Self-Efficacy

Teaching is one such profession in which it is truly a boon to have a strong sense of self-efficacy. After all, you need it to deal with young, energetic, and/or hormonal students all day!

It is no surprise, then, that self-efficacy is a natural protective factor against teacher job strain, job stress, and burnout. High levels of job stress are strongly related to subsequent burnout, but high self-efficacy acts as an effective barrier between job stress and burnout (Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008).

Research on the self-efficacy of teachers suggests that there are six components to the overall construct that act as a buffer between teaching stress and teacher burnout:

- Instruction;

- Adapting Education to Individual Students’ Needs;

- Motivating Students;

- Keeping Discipline;

- Cooperating with Colleagues and Parents;

- Coping with Changes and Challenges (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007).

Generally, when teachers believe in their ability to effectively instruct students, adapt the lessons to individual students’ needs, etc., they have a high level of overall self-efficacy related to teaching. This six-factor construct has also been shown to correlate with burnout, i.e., greater self-efficacy leads to less burnout (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007).

As with other populations, the best way to develop greater self-efficacy in teachers is to focus on mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, getting positive and encouraging feedback, and general self-care; however, when applied conscientiously to these six components, teachers may find the most effective way to boost overall self-efficacy.

Increasing Academic Performance in Students

In addition to helping teachers get through their day with their dignity and spirit intact, self-efficacy has great potential in aiding student performance.

Students with high self-efficacy also tend to have high optimism, and both variables result in a plethora of positive outcomes: better academic performance, more effective personal adjustment, better coping with stress, better health, and higher overall satisfaction and commitment to remain in school (Chemers, Hu, & Garcia, 2001).

Although these effects are enhanced for students with high GPAs, self-efficacy can also improve performance for students with a less natural aptitude for academics.

For students who struggle with reading, self-efficacy is both an outcome and a key to their continued success. Teachers who promote self-efficacy in struggling readers are apt to find that those students are more enthusiastic about and more committed to learning than those who have not received encouragement through gradual progress (Margolis & McCabe, 2006).

Researchers Margolis and McCabe (2006) recommend that teachers focus on boosting students’ self-efficacy through three sources of self-efficacy:

- Enactive mastery;

- Vicarious experiences;

- Verbal persuasion.

By giving students the opportunity to experience small wins, celebrating even the little successes, modelling motivation and hard work, and offering verbal encouragement, teachers can help their students build the self-efficacy that will serve them throughout their academic career and beyond.

All students can benefit from a healthy level of self-efficacy, but those that go into a healthcare field may enjoy some added advantages.

Self-Efficacy in nursing and health care

The longer a nurse has worked in a clinical setting, the higher the nurse’s belief in his or her ability to do the job and do it well.

Since mastery experiences promote self-efficacy, it is unsurprising that more hands-on experience leads to higher self-efficacy.

It also makes sense that nurses with a bachelor’s degree reported greater self-efficacy than those with a diploma, as advanced education provides plenty of mastery experiences as well as giving nurses access to role models and (hopefully!) supportive teachers, mentors, and supervisors (Soudagar et al., 2015).

The benefits of enhancing nurses’ self-efficacy are numerous; in addition to influencing how well they perform the functions of their role, it can also act as a buffer between nurses and negative or unhealthy workplace behaviors, protect them from burnout, and reduce turnover intentions (Fida, Laschinger, & Leiter, 2018).

It is vital for nurses and other healthcare professionals to have a sense of self-efficacy when it comes to their ability to take care of patients, and it also benefits the patients receiving care (Hoffman, 2013).

As it turns out, self-efficacy offers some wonderful benefits for patients. Cancer patients with high self-efficacy have higher intentions to quit smoking, participate in screening programs more frequently, and adjust to their diagnosis better than those with low self-efficacy (Lev, 1997).

Further, they are more likely to adhere to treatment, take care of themselves, and experience fewer and less severe physical and psychological symptoms (Lev, 1997).

Not only does self-efficacy provide benefits for cancer patients, but it also helps patients with renal disease to gain weight—an important goal in this sort of disease (Tsay, 2003). Self-efficacy can enhance the quality of life for patients receiving dialysis as well (Tsay, 2002), and results in increased exercise and better post-surgery performance in joint-replacement patients (Moon & Backer, 2000).

Increasing self-efficacy in nurses and patients certainly seems to pay off. This leads to the question: Does self-efficacy improve performance in all professions and contexts?

Increasing job performance in the workplace

A meta-analysis by Stajkovic and Luthans (1998) gathered the data from over 100 separate studies on the relationship between self-efficacy and job performance and produced some groundbreaking results.

They found that there was a correlation of .38 between self-efficacy and work-related performance—this may not seem like much, but in psychology, a correlation of .38 is generally considered quite the connection!

This indicates that there is a strong linkage between self-efficacy and job performance. Certainly, some portion of this relationship is explained by successful performance influencing self-efficacy, but there is plenty of evidence to suggest the opposite is a significant relationship as well: that increasing self-efficacy results in better job performance, on average.

Another meta-analysis was conducted a few years later, and found results that were just as significant—self-efficacy was found to relate to job performance as well as job satisfaction (Judge & Bono, 2001). This indicates that not only do those with high self-efficacy tend to perform better in their jobs, they also tend to like their jobs more.

In addition, the study found evidence that self-esteem, self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability were all related, and all positively influenced job performance and job satisfaction.

This relationship between self-efficacy and performance seems especially important in the context of startups and entrepreneurial endeavours.

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

To start with, self-efficacy has an impact on entrepreneurs before they even become entrepreneurs. Researchers Zhao, Seibert, and Hills (2005) found that self-efficacy fully explained the relationship between learning in entrepreneurial courses, previous entrepreneurial experience, and the willingness to take the risk of becoming an entrepreneur and an individual’s entrepreneurial intentions.

In other words, self-efficacy is the secret ingredient leading from learning about entrepreneurship to actually taking the leap to become an entrepreneur.

Once an entrepreneur sets his or her feet on this path, self-efficacy continues to serve them well. A specific type of self-efficacy called entrepreneurial self-efficacy develops in those who have the drive and the belief in themselves to establish their own business, and this type of self-efficacy is positively related to beliefs in one’s knowledge and ability to handle finances, management, and marketing (Chena, Greeneb, & Crickc, 1998).

Further, self-efficacy may even provide individuals with the push they need to set out on their entrepreneurial adventure. Research suggests that self-efficacy may be the vital factor in encouraging would-be entrepreneurs to create formal business plans, conduct opportunity analyses, and engage in other productive, goal-directed behavior (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994).

Self-efficacy in sport and exercise

Yet another area in which self-efficacy has a marked effect on performance is in sports and exercise.

A meta-analysis of 45 studies published in 2000 found that the correlation between self-efficacy and sports performance was a solid .38 (Moritz, Feltz, Fahrbach, & Mack). This indicates a moderate-to-strong relationship between the two, suggesting that—as in other realms—firm belief in one’s own abilities has the potential to boost performance in the chosen activity.

Not only can higher self-efficacy act as a motivator for athletes, it can also act as a catalyst and encouragement for those who simply wish to exercise more often, get healthy, or lose weight.

A study of nearly 1,500 participants offered evidence that exercise self-efficacy was strongly related to the participants’ readiness to change (Marcus, Selby, Niaura, & Rossi, 1991). This suggests that those who improve their self-efficacy in relation to exercise may skip some steps on the ladder of motivation and readiness to change, resulting in faster and more impactful results.

The research also shows that older adults may be particularly suited to focusing on self-efficacy; studies have shown that self-efficacy has a significant impact on (previously) sedentary middle-aged adults’ exercise behavior, resulting in more aerobic activity and better health (McAuley, 1992).

This boost in self-efficacy can have a positive impact on self-esteem and body satisfaction as well as physical health in middle-aged adults, a benefit that should not be overlooked (McAuley, Mihalko, & Bane, 1997).

We know that improved physical health often leads to improved mental health, but does self-efficacy have a direct impact on mental health as well?

Self-efficacy and stress, depression, and anxiety

Self-efficacy has been positively linked to stress management and relief from the symptoms of depression and anxiety, and may even act as a buffer between the individual and the development of depression and anxiety disorders.

Self-efficacy in the context of academic performance is related to higher first-year college grade point average (GPA), more credits earned, and higher retention rates, even when students struggle with the stresses of higher education (Zajacova, Lynch, & Espenshade, 2004). Although high stress can hinder achievement in school, high self-efficacy acts as a buffer and motivator, boosting students’ academic success.

Self-efficacy can also provide new mothers with protection against the ravages of the high-stress situation when a new baby is brought home. The new mothers’ self-efficacy related to parenting acted as a mediator between temperamental infants and postpartum depression (Cutrona & Troutman, 1986).

Social support also protected mothers from the effects of postpartum depression, and this factor was also related to self-efficacy!

Research has established that stress can lead to or exacerbate symptoms of depression, indicating that self-efficacy can indirectly make a positive impact on depression; however, research has also shown a direct impact of self-efficacy on depressive symptoms.

Research from self-efficacy founding father Albert Bandura provided evidence that self-efficacy protects children from developing childhood depression, or at least protects them from the most severe and pervasive symptoms of depression (Bandura, Pastorelli, Barbaraenelli, & Caprara, 1999). Unsurprisingly, children with academic inefficacy suffered due to their lack of belief in themselves, particularly girls.

Getting back to mothers of young children, self-efficacy can also benefit them in another way. Not only can it protect them against the high-stress context of raising a young child, but also it can help protect them against depression.

Mothers with low self-efficacy in relation to their parenting skills are more vulnerable to depression than those with a healthier sense of self-efficacy (Gross, Conrad, Fogg, & Wothke, 1994). On the other hand, those with high self-efficacy were less likely to report experiencing depressive symptoms, even when they had a wild and exuberant toddler on their hands.

Self-employed workers are another group that enjoys the benefit of protection against depression when their self-efficacy is high. Those who are self-employed and high in self-efficacy not only enjoy lower levels of depression, they also experience greater job satisfaction (Bradley & Roberts, 2003).

High self-efficacy can act as a protective factor against anxiety as well as depression, or it can serve as an exacerbating factor when it is low. In adolescents, low self-efficacy is strongly related to anxiety and neuroticism, anxiety disorder symptoms, and depressive symptoms (Muris, 2002). Further, those with low self-efficacy were also more likely to experience social phobia, school phobia, and panic disorders.

This relationship is not limited to children; high-school athletes also benefit from high self-efficacy. When they have a solid belief in their own abilities related to sports performance, they are protected against the negative effects of performance anxiety (Martin & Gill, 1991).

This link between self-efficacy and anxiety was initially proposed by Bandura himself; he noted that low self-efficacy is basically the belief that one does not have control over a situation and cannot manage potential threats, which logically leads to increased anxiety (1988).

This result can spark (or continue) a self-repeating cycle in which low self-efficacy leads to greater anxiety and greater avoidant behaviors, which leads to fewer master experiences and fewer opportunities to successfully cope with distress, which in turn lowers the individual’s self-efficacy even more (Bandura, 1988).

Viewed in this light, it makes perfect sense that self-efficacy and anxiety share the strong relationship that they do.

Two Vital Books on Self-Efficacy

The best way to learn about a subject is from an expert—and who could be more of an expert on self-efficacy than Bandura himself? These two books (one written by Bandura, one edited by Bandura) are essential for anyone who wants to familiarize themselves with this topic.

1. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control – Albert Bandura

This book is a must-read for anyone interested in self-efficacy, and an imperative for anyone who wants to learn about Bandura’s view on self-efficacy and Social Learning Theory.

In these pages, you will learn about what we have learned over 20 years of Bandura’s research on the subject, and explore the relationship between self-efficacy and perceived self-efficacy.

It is written in an accessible manner and makes it easier than ever to understand some of the complex concepts and ideas surrounding self-efficacy.

See for yourself what makes Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control a “landmark book”.

Find the book on Amazon.

2. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies – Albert Bandura

This is another one of the seminal works on self-efficacy from Albert Bandura.

Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies is an edited volume filled with chapters written by the foremost experts on self-efficacy in the 1990s.

It serves as a valuable resource for anyone interested in self-efficacy, including researchers, therapists, counselors, parents, and coaches.

This book walks the reader through an exploration of self-efficacy and how it impacts the decisions we make and where we end up.

It also covers related topics and factors that influence or are affected by self-efficacy, including:

- Infancy and personal agency;

- Competency through the lifespan;

- The role of family;

- Cross-cultural factors;

- Human adaptation and change in general.

Find the book on Amazon.

11 Self-Efficacy Quotes

If the facts and straightforward explanations of self-efficacy’s impact don’t get you fired up and motivated to work on developing and maintaining your sense of self-efficacy, perhaps one of these quotes on the subject will do it for you!

“In order to succeed, people need a sense of self-efficacy, to struggle together with resilience to meet the inevitable obstacles and inequities of life.”

Albert Bandura

“If I have the belief that I can do it, I shall surely acquire the capacity to do it even if I may not have it at the beginning.”

Mahatma Gandhi

“Self-belief does not necessarily ensure success, but self-disbelief assuredly spawns failure.”

Albert Bandura

“I want to thank my parents for giving me confidence disproportionate to my looks and abilities, which is what all parents should do.”

Tina Fey

“If self-efficacy is lacking, people tend to behave ineffectually, even thought they know what to do.”

Albert Bandura

“They are able who think they are able.”

Virgil

“Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the sources of action required to manage prospective situations.”

Albert Bandura

“You have brains in your head and feet in your shoes, you can steer yourself in any direction you choose!”

Dr. Seuss

“Strength and growth come only through continuous effort and struggle.”

Napoleon Hill

“People’s beliefs about their abilities have a profound effect on those abilities.”

Albert Bandura

“Self-belief, also called self-efficacy, is the kind of feeling you have when you have, like a Jedi, mastered a particular kind of skill and with its help have been able to achieve your set goals.”

Stephen Richards

A Take-Home Message

To put it in the simplest terms possible, the take-home message of this piece is: you can do it.

If you already have a strong belief in your ability, remind yourself that you can do it. If you’re uncertain about your capacity for success, tell yourself that you can do it.

If you’re positive that there is no way you could achieve the goal you set for yourself or overcome the obstacle in your path, give yourself a stern but encouraging pep talk (“You can do it!”).

We know that a person’s belief in their own abilities is a strong predictor of motivation, effort expended, and success; there is no downside to encouraging yourself, and working on believing in yourself.

As Henry Ford said, “Whether you think you can or you can’t, you’re right.” So what happens when we think that we can?

What do you think about the research on self-efficacy? Is there anything that jumped out at you? What do you do to boost your own self-efficacy or that of the children, patients, or employees in your life? Let us know in the comments.

Thanks for reading!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self Compassion Exercises for free.

- Akhtar, M. (2008). What is self-efficacy? Bandura’s 4 sources of efficacy beliefs. Positive Psychology UK. Retrieved from http://positivepsychology.org.uk/self-efficacy-definition-bandura-meaning/

- Bandura, A. (1988). Self-efficacy conception of anxiety. Anxiety Research, 1, 77-98.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

- Bandura, A. (1999). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. In Roy F. Baumeister’s (Ed.) The self in social psychology (pp. 285-298). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Bandura, A., Pastorelli, C., Barbaranelli, C., & Caprara, G. V. (1999). Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 258-269.

- Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18, 63-77.

- Bradley, D. E., & Roberts, J. A. (2003). Self-employment and job satisfaction: Investigating the role of self-efficacy, depression, and seniority. Journal of Small Business Management, 42, 37-58.

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 62-83.

- Chena, C. C., Greeneb, P. G., & Crickc, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 295-316.

- Chemers, M. M., Hu, L., & Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 55-64.

- Cherry, K. (2017). Self efficacy: Why believing in yourself matters. Very Well Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-self-efficacy-2795954

- Cutrona, C. E., & Troutman, B. R. (1986). Social support, infant temperament, and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Development, 57, 1507-1518.

- Fida, R., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Leiter, M. P. (2018). The protective role of self-efficacy against workplace incivility and burnout in nursing: A time-lagged study. Health Care Management Review, 43, 21-29.

- Gross, D., Conrad, B., Fogg, L., & Wothke, W. (1994). A longitudinal model of maternal self-efficacy, depression, and difficult temperament during toddlerhood. Research in Nursing & Health, 17, 207-215.

- Hoffman. A. J. (2013). Enhancing self-efficacy for optimized patient outcomes through the theory of symptom self-management. Cancer Nursing, 36, E16-E26.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluation traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 80-92.

- LaMorte, W. W. (2016). The social cognitive theory. Boston University School of Public Health. Retrieved from http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/SB/BehavioralChangeTheories/BehavioralChangeTheories5.html

- Lev, E. L. (1997). Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy: Applications to oncology. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 11, 21-37.

- Marcus, B. H., Selby, V. C., Niaura, R. S., & Rossi, J. S. (1991). Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 63, 60-66.

- Margolis, H., & McCabe, P. P. (2006). Improving self-efficacy and motivation: What to do, what to say. Intervention in School and Clinic, 41, 218-227.

- Martin, J. J., & Gill, D. L. (1991). The relationships among competitive orientation, sport-confidence, self-efficacy, anxiety, and performance. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 13, 149-159.

- Mayer, R. E. (2010). Motivation based on self-efficacy. Education.com. Retrieved from https://www.education.com/reference/article/motivation-based-self-efficacy/

- McAuley, E. (1993). Self-efficacy and the maintenance of exercise participation in older adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 103-113.

- McAuley, E., Mihalko, S. L., & Bane, S. M. (1997). Exercise and self-esteem in middle-aged adults: Multidimensional relationships and physical fitness and self-efficacy influences. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20, 67-83.

- Moon, L. B., & Backer, J. (2000). Relationships among self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and postoperative behaviors in total joint replacement patients. Orthopedic Nursing, 19, 77-85.

- Moritz, S. E., Feltz, D. L., Fahrbach, K. R., & Mack, D. E. (2000). The relation of self-efficacy measures to sport performance: A meta-analytic review. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71, 280-294.

- Muris, P. (2002). Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 337-348.

- Neill, J. (2005). Definitions of various self constructs. Wilderdom. Retrieved from http://www.wilderdom.com/self/

- Proctor, C., Maltby, J., & Linley, P. A. (2011). Strengths use as a predictor of well-being and health-related quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 153-169.

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 23, 7-25.

- Schwarzer, R., & Hallum, S. (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: Mediation analyses. Applied Psychology, 57, 152-171.

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.) Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio (pp. 35-37). Windsor, UK: Nfer-Nelson.

- Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The Self-efficacy Scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51, 663-671.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 611-625.

- Soudagar, S., Rambod, M., & Beheshtipour, N. (2015). Factors associated with nurse’s self-efficacy in clinical setting in Iran, 2013. Iran Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 20, 226-231. PMCID: PMC4387648

- Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240-261.

- Tsai, C. L., Chaichanasakul, A., Zhao, R., Flores, L. Y., & Lopez, S. J. (2014). Development and validation of the strengths self-efficacy scale (SSES). Journal of Career Assessment, 22(2), 221-232.

- Tsay, S. (2002). Self-care self-efficacy, depression, and quality of life among patients receiving hemodialysis in Taiwan. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39, 245-251.

- Tsay, S. (2003). Self-efficacy training for patients with end-stage renal disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 43, 370-375.

- Zajacova, A., Lynch, S. M., & Espenshade, T. J. (2005). Self-efficacy, stress, and academic success in college. Research in Higher Education, 46, 677-706.

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1265-1272.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Hi Nicole! I am grateful for this article. This is a lot of help in my ongoing research paper. I am working on the self-efficacy and motivation of out-field-teachers, can you recommend what kind of self-efficacy scale and questionnaire should I use? Your reply is very much appreciated.

Hi there,

Thank you for your kind words! I’m thrilled to hear that the article has been helpful in your research journey.

I would recommend considering the use of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) for measuring self-efficacy. It’s a widely recognized and validated tool that can provide insightful data on individuals’ beliefs in their ability to handle different situations.

I hope this helps! Feel free to reach out if you have any more questions or need further clarification. Wishing you the best of luck with your research paper!

Warm regards,

Julia | Community Manager

Hi!This is what I’m searching for. Thank you for this article! This helps me a lot for my research! Wish me luck for my undergraduate thesis🙏🎓

Very glad to see this post and useful for the researchers. Educationalists and Researches will get more ideas on this information for further course of study.

Thank you author for sharing such a wonderful research information.

Hi. There is a misspelling in the “Self-sfficacy and motivation” paragraph.

Hi Jason,

Whoops! Thanks for bringing this to our attention. We’ve corrected this now 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager

Hello. I would like some source or articles about “The role of self-efficacy across various stages of life?”

Please let me know if you have any leads

Hi John,

Madhuleena compiled a very comprehensive article about self-efficacy, with one section dedicated to the development of it. However, I would recommend reading the whole article 4 Ways To Improve And Increase Self-Efficacy. In addition, you might find more information in this must-read: Albert Bandura: Self-Efficacy for Agentic Positive Psychology regarding self-efficacy.

Hope this helps!

Annelé

Hello,

Fabulous article. Thank you.

What have you come across regarding the relationship between positive self talk and self efficacy? Specifically how the constructs can be used together in competitive sports to enhance performance?

Working on a PsyD. Any thoughts are greatly appreciated.

Thank you

Hi Robym

Glad you enjoyed the post — thank you! Positive self-talk in the context of competitive sports (often colloquially referred to as ‘psyching oneself up’) is actually pretty thoroughly researched and has been shown to be effective for strengthening performance!

You’ll find a good summary of these links here (with the links throughout the article taking you to journal articles evidencing the findings):

http://thesportdigest.com/2020/07/the-science-behind-motivational-self-taking-and-psyching-oneself-up/

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Thank you very much for this very useful article on self efficacy. It has clearly set the tone for my seminar paper on self efficacy.

By the way, if one is studying the self efficacy of a group of people in remote or virtual working, please what sort of self efficacy scale and questionnaire would you recommend for measuring their self efficacy?

Hi Tolase,

Glad you found this post useful. Regarding your question, I’d recommend taking a look at the Virtual Work Self-Efficacy Scale used by Adamovic et al. (2021). You’ll find the four items under the measures section on page 14.

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Hi Nicole,

Thank you so much for your quick response. The work by Adamovic et al. (2021) is indeed very useful. Sorry I couldn’t confirm this earlier.

Hi Tolase,

That’s okay! Glad I could help 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager

What is the difference, if any, between Self-efficacy and human agency?

Thanks.

Human agency describes the ability to choose whereas self-efficacy is the belief that we can perform well in a choice. I practice my agency when I believe I have choices, I can choose to believe that I can do well at a task or choose to believe that I will not do well in a task therefore decreasing or increasing my self-efficacy in a particular task. For example, I may choose to be interested in playing basketball and choose to build motivation towards playing basketball. I have people telling me that I am doing well and I played a good game, if I choose (practice agency) to believe their input it increase my self-efficacy in playing basketball.

I hope this helps!