What is Eudaimonia? Aristotle and Eudaimonic Wellbeing

There are a million different ways to define happiness.

There are a million different ways to define happiness.

Especially in the field of psychology, where operational definitions are a constant work in progress.

Eudaimonia is not only one of the oldest, but it has stood the test of time for another reason.

That reason being, eudaimonia has the whole element of subjectivity built into it. It’s simultaneously both less and more prescriptive and dives quite deeply into the ideas of virtues and virtue ethics.

In this article, we’ll look at Aristotle’s definition of Eudaimonia and its significant influence on the way ‘happiness’ and ‘wellbeing’ are viewed in positive psychology. Most significantly, through its implications for subjective wellbeing.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

This Article Contains:

- What is Eudaimonia? (Incl. Definition)

- A Brief History of Eudaimonia

- A Look at Aristotle’s Concept of Happiness and Wellbeing

- The Philosophy Behind Aristotle’s Ethics

- Modern Psychology and Eudaimonia

- Plato on Eudaimonia

- Socrates and Eudaimonia

- 3 Examples of Eudaimonic Wellbeing

- Eudaimonic Wellbeing Scale and Questionnaire (PDF)

- 5 Tips on How to Achieve Eudaimonia

- 9 Eudaimonic Activities to Promote Human Flourishing

- How Can One Best Practice Virtue?

- Eudaimonic vs Hedonic: What’s the Difference?

- The Eudaimonia Institute

- 6 YouTube Videos

- 3 Recommended Books

- 7 Quotes on the Topic

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Eudaimonia? (Incl. Definition)

In its simplest (translated) form, eudaimonia is often taken to mean happiness (Deci & Ryan, 2006; Huta & Waterman, 2014; Heintzelman, 2018). Sometimes it is translated from the original ancient Greek as welfare, sometimes flourishing, and sometimes as wellbeing (Kraut, 2018). The concept of Eudaimonia comes from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, his philosophical work on the ‘science of happiness’ (Irwin, 2012).

We’ll look at this idea of ‘the science of happiness’ a little more closely later in this article.

Eudaimonia is about individual happiness; according to Deci and Ryan (2006: 2), it maintains that:

“…wellbeing is not so much an outcome or end state as it is a process of fulfilling or realizing one’s daimon or true nature—that is, of fulfilling one’s virtuous potentials and living as one was inherently intended to live.”

As there are so many different ways to translate the term into English, it may even be helpful to look at the etymology. If it helps to provide more context, eudaimonia is a combination of the prefix eu (which means good, or well), and daimon (which means spirit) (Gåvertsson, n.d.). The latter also appears in various related forms in contemporary literature, such as the idea of a dæmon as one’s soul in Philip Pullman’s bestselling Northern Lights (Oxford Dictionaries, 2019).

A Brief History of Eudaimonia

As noted, the concept of Eudaimonia can be traced back to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Prior to this, however, Athenian philosophers such as Socrates and Plato (Aristotle’s mentor) were already entertaining similar concepts.

Socrates on Eudaimonia

Socrates, like Plato, believed that virtue (or arête, the very idea of virtue) was a form of knowledge—specifically, a knowledge of good and evil (Bobonich, 2010). That is, he saw numerous virtues—justice, piety, courage as united. That is, all were one, and they were all knowledge.

Socrates viewed this knowledge as required for us as humans to achieve the ‘ultimate good’, which was eudaimonia. And by ‘us’, Socrates meant the individual (Waterman, 1993; Deci & Ryan, 2006).

Plato and Eudaimonism

In a somewhat similar vein, Plato believed that individuals naturally feel unhappiness when they do something they know and acknowledge to be wrong (Price, 2011). Eudaimonia, according to Plato, was the highest and ultimate aim of both moral thought and behavior.

Nonetheless, while Plato was believed somewhat to have refined the concept, he offered no direct definition for it. As with Socrates, he saw virtue as integral to eudaimonia.

One thing is worth noting at this point. If this idea of an ‘ultimate goal’ for individuals is beginning to sound familiar, rest assured that there is good reason for thinking so. The similarities between eudaimonia and concepts such as Maslow’s self-actualization (1968) are indeed widely accepted in the psychological literature (Heintzelman, 2018).

Given that we know Plato mentored Aristotle, let’s look at what the latter believed.

Aristotlean Eudaimonia

Numerous interpretations have been offered for Aristotle’s eudaimonia, with a general consensus on the idea that eudaimonia reflects “pursuit of virtue, excellence, and the best within us” (Huta & Waterman, 2014: 1426). That is, he believed eudaimonia was rational activity aimed at pursuing ‘what is worthwhile in life’.

Where Aristotle diverged from Plato and some other thinkers is in his belief about what is ‘enough’ (roughly) for eudaimonia. For the latter, virtue was enough for the ultimate good that is eudaimonia. For Aristotle, virtue was required, but not sufficient (Annas, 1993). In layperson’s terms, we can’t just act with virtuous, but we have also to intend to be virtuous, too.

I will return to this a little later when looking at Aristotle’s ethics. But for now, he believes that happiness and wellbeing come from how we live our lives. And that’s not in pursuit of material wealth, power, or honor. Rather, eudaimonic happiness is about lives lived and actions taken in pursuit of eudaimonia.

Also at this point, you probably understand why some translations are argued to fall a little flat when it comes to describing Aristotle’s philosophical concept. Where rational activity is required to pursue an ultimate goal, beings such as plants—which do ‘flourish’—don’t qualify.

Where these rational activities include “pride, wittiness, friendships that are mutually beneficial, pride and honesty among others”, neither do lots of other creatures (Hursthouse, 1999).

A Look at Aristotle’s Concept of Happiness and Well-Being

If you could ask Aristotle himself what happiness is, this is exactly what he’d say:

“…Some identify happiness with virtue, some with practical wisdom, others with a kind of philosophic wisdom, others with these, or one of these, accompanied by pleasure or not without pleasure; while others include also external prosperity…it is not probable that…these should be entirely mistaken, but rather that they should be right in at least some one respect or even in most respects.”

Aristotle, Nichomacean Ethics, Book I, Chapter 8 (excerpt from Nothingistic.org, 2019)

Happily, we also have more concise and straightforward excerpts that reveal how we go about it.

Happy Life According to Aristotle

To be honest, a lot of Nichomacean Ethics is about what happiness isn’t. ‘Satisfying appetites’, Ryan and Singer argue is akin to “life suitable to beasts”, according to the philosopher (2006: 16). The pursuit of political power, material wealth, even fun and leisure, he saw as “laughable things”, inferior to “serious things” (Ryff & Singer, 2008: 16).

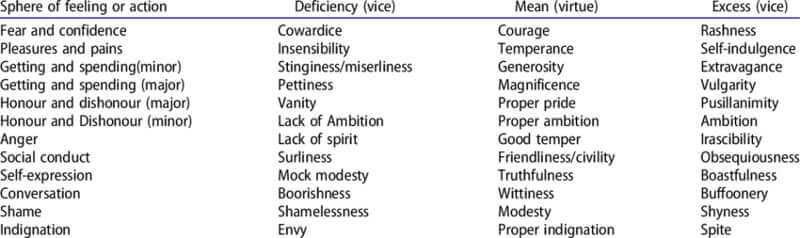

Instead, happiness is an ‘intermediate’, or a ‘golden mean’ between deficiency and excess (Ryff & Singer, 2008). One example of virtue as a mean between two extremes is courage – as a virtue, it’s halfway between recklessness and cowardice (Kings College London, 2012).

Here, we see the ‘rational activity’ aspect of eudaimonia coming back to the fore. When we are faced with situations, therefore, it can be argued that Aristotle isn’t giving prescriptive advice. He is, however, telling us how he believes the rational, virtuous pursuit of eudaimonia might look in an everyday setting.

Role of Externalities

So, what if you’re very, very unlucky?

If you’ve read Nichomacean Ethics (maybe only skimmed partway through), this question is not an unreasonable one. After all, Aristotle argued:

“He is happy who lives in accordance with complete virtue and is sufficiently equipped with external goods, not for some chance period but throughout a complete life.” – Aristotle, Nichomacean Ethics, Book I, Chapter 10 (excerpt from Nothingistic.org, 2019).

Basically, yes, Aristotle acknowledged that fate or luck can play a role in our happiness. Nonetheless, he also believed that this task of ‘individual self-realization’ is how we go about it with our ‘own disposition and talent’ (Ryff & Singer, 2008: 17).

This excerpt also suggests that we should be aiming for ‘all of the virtues’, so it’s worthwhile considering Aristotle’s stance on being virtuous.

The Philosophy Behind Aristotle’s Ethics

As we can now see, Aristotle’s eudaimonia is a moral happiness concept. It is very much about living a life in accordance with virtues (Hursthouse, 1999).

But what are these virtues, then?

Of course, there is a large subjective element to what ‘virtue’ is. What one person holds to be virtuous isn’t always going to ring with that of others. Ancient and Medieval Philosophy Professor Peter Adamson gives some brilliant examples in this Kings College London video:

One of these is ‘piety’, which was mentioned in the earlier look at Socrates. For example, can you be too pious? Some would argue yes, others, no.

From what we’ve already discussed, however, we know Aristotle believes happiness is not about pursuing eudaimonia through various means in order to be happy. This is, he argues, is founded in instrumentality. Happiness, he might be seen as arguing, is once again the rational activity in pursuit of virtue itself.

These virtues won’t necessarily be cut in stone. But, if we ask ourselves what we believe is good, or how we should live our lives, virtue ethics would argue that we have at least some starting points (Hursthouse, 1999).

Modern Psychology and Eudaimonia

So far, we’ve looked a little bit at subjectivity, flourishing, happiness, wellbeing, and actualization. All in a philosophical context.

Hopefully, it provided some context. Because, naturally, eudaimonia thus has myriad implications for psychologists with an interest in subjective wellbeing (SWB), and psychological wellbeing (PWB). And positive psychology is all about human flourishing and happiness.

Overview of Psychological Research on Eudaimonia

As a very concise overview of how the concept appears within psychology, here are some aspects that have been studied:

- Definition – not only conceptualizing the idea of eudaimonia in terms of psychology, wellbeing, and happiness, but also trying to operationalize the concept (e.g. Waterman, 1993; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Keyes, 2002; Bauer et al., 2008; Ryff & Singer, 2008; Waterman et al. 2008);

- Measurement – lots of these attempts at operationalization are a preliminary step to measuring human experiences of eudaimonia.

- There are actually a fair few of these scales. The best-known actually measures a similar concept of psychological wellbeing (PWB), made famous by Professor Ryff (1989);

- Distinctiveness and relation to other happiness/wellbeing concepts – with the most popular earlier studies looking at eudaimonia alongside hedonia (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Huta & Waterman, 2014);

- This was accompanied by empirical and statistical analyses of the same (Chen et al., 2013); and

- Studies have also looked at how eudaimonia is related (or not) to PWB and SWB (e.g. Chen et al., 2013).

Of course, this is far from an exhaustive list, and as interdisciplinary interest grows, we can expect the same from the broader body of research.

Plato on Eudaimonia

As mentioned above, Plato never distinctly referred to eudaimonia by that term. A lot of what we know about his stance on the same comes from Republic (Amazon), his work on justice. In it, he writes of three friends who talk about what a ‘just’ republic would look like, and he premised four virtues (Bhandari, 1999; VanderWeele, 2017):

- Temperance (moderation) – or self-regulation, to avoid the vices and corruption caused by excess;

- Courage (or fortitude) – to stand up for what we believe is right and good;

- Justice – a social consciousness that plays a key part in maintaining societal order; and

- Wisdom (practical wisdom, or prudence) – the pursuit of knowledge.

He believed that happiness was about living in pursuit of these virtues, and thus virtue is central to flourishing.

Socrates and Eudaimonia

Socrates, as discussed, saw eudaimonia as an ‘ultimate’ goal. Like Aristotle after him, Socrates emphasized the role and importance of arête very heavily—in fact, he believed it was both a means and an end to human happiness. In pursuit of what we now commonly refer to as ‘flourishing’, he encouraged people to ask themselves, and others, what was ‘good’ for our souls (Cooper, 1996).

He believed, it is argued, that eudaimonia was ‘justly living well’, and that in doing so, we seek not experiential pleasure or ‘honor’ in isolation, but a good and happy life, guided by our virtues (Cooper, 1997; Bobonich, 2010; Brown, 2012).

3 Examples of Eudaimonic Wellbeing

A couple of millennia later, the teachings of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle continue to shape how we study flourishing and wellbeing.

Modern conceptions of Eudaimonic Wellbeing (EWB) are, on the whole, shaped by literature reviews, critical analyses, and empirical examinations of their texts. Coupled with modern research into quality of life and subjective wellbeing (SWB), we have come as far as being able to develop measures for the construct.

EWB is defined by Waterman and colleagues (2010: 41) as:

“quality of life derived from the development of a person’s best potentials and their application in the fulfillment of personally expressive, self-concordant goals

(Sheldon, 2002; Waterman, 1990; 2008)”

In their study, they give several examples of EWB (Norton, 1976; Waterman et al., 2010). Here are a few:

- “Knowing who you really are” – Examples of this self-discovery might include the self-identity knowledge that comes from meditating on your core beliefs. Or, it could be a good understanding of your personal character strengths and qualities. It could even be the self-knowledge that comes from reflecting on your personal development or the values that you hold important.

- “Developing these unique potentials” – Someone who scores high on EWB (according to the Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Wellbeing) makes a persistent, committed effort to building on this self-knowledge. A little more on the ‘how’ and the QEWB is covered very shortly.

- “Using those potentials to fulfill your life goals” – Someone who is committed to this pursuit, over the long term, would be a prime example.

These describe some of the EWB concepts on which one well-known measure of EWB is based.

Eudaimonic Wellbeing Scale and Questionnaire (PDF)

Interested in finding out how you score on a Eudaimonic Wellbeing Scale? The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Wellbeing (QEWB) was developed by the same Waterman as above, and measures one’s (Waterman et al., 2010):

- A sense of meaning and purpose in life – which describes the personally meaningful objectives that we direct our talents and skills toward;

- Enjoyment derived from activities that are ‘personally expressive’ – a high score on this contributes to a higher Eudaimonic Wellbeing (EWB) score overall;

- Intense involvement in activities – not just any activities or hobbies, but those that are related to our life goals (see point 1 above);

- Perceived development of their own best potentials – this relates back to Aristotle’s idea of ‘fulfilling one’s virtuous potentials’; and

- Investment of significant effort – towards achieving excellence.

QEWB Items

Some items from the QEWB include (Waterman et al., 2010):

- Other people usually know better what would be good for me to do than I know myself. (Reverse scored)

- If I did not find what I was doing rewarding for me, I do not think I could continue doing it.

- When I engage in activities that involve my best potentials, I have this sense of really being alive.

- I find a lot of the things I do are personally expressive for me.

- My life is centered around a set of core beliefs that give meaning to my life.

- It is important to me that I feel fulfilled by the activities that I engage in.

- I find it hard to get really invested in the things that I do. (Reverse scored)

Interestingly, the findings of this study suggest that EWB may be conceptually distinct from both subjective wellbeing (SWB) and psychological wellbeing (PWB) as a measure of wellbeing.

The 21-item scale can be found in its entirety (PDF) in Waterman and colleagues’ original article.

5 Tips on How to Achieve Eudaimonia

If we unpack Deci & Ryan’s earlier definition of eudaimonia, we can discern a few actionable tips. Put them together with Waterman and colleagues’ QEWB scale above, and we have the following.

1. Know your ‘life goals’

A terribly lofty goal at first glance, but as we can see from the scale items above, this doesn’t have to mean a ten-, thirty- or fifty-year plan. It doesn’t mean we need to aspire to achieve something or ‘die trying’ either.

It is seemingly enough to have, or to strive to have, a sense of the core beliefs which guide you and which give meaning to your existence.

How about: “To bring happiness to others” or “To help those who are suffering”?

2. Focus your capabilities and skills towards achieving those goals

Are you a kind person? Great with kids? A talented doctor? Can you direct your skills towards achieving those goals for the sake of practicing virtue?

The last is a particularly interesting example, discussed in the YouTube above from Kings College London. It describes how the idea isn’t to become a doctor because that’s going to make you happy, but because you’re aiming to fulfill your own unique best potentials. And of course, to live in accordance with your virtues.

3. Developing your best potentials

As above, it’s about being the best you can be, driven by authentic and meaningful goals. Stretching that ‘doctor’ example a little further, this would be distinct from wanting to be ‘The Best Doctor You Can Be’ for the pay.

4. Get engaged in these activities

To derive meaning from this development is to experience eudaimonia. Why? Because it’s the pursuit itself, and eudaimonia is not an end goal. If this all sounds very confusing, it may help to reflect back on Huta & Waterman’s (2014) definition once more, in which eudaimonia is the “pursuit of virtue, excellence, and the best within us” (Huta & Waterman, 2014: 1426).

5. Express yourself

This means a little more than it seems at first glance. Waterman and colleagues, in creating the QEWB, describe this as engaging in behavior that expresses ‘who you are’, not just ‘how you feel’. And, they note that people scoring high in EWB tend to engage in these activities much more often than those who don’t.

In other words, doing things because you derive genuine enjoyment from them and because they’re consistent with your view of yourself, rather than for external reward.

9 Eudaimonic Activities to Promote Human Flourishing

According to Schotanus-Dijkstra and colleagues (2016), flourishing describes people who have both high levels of EWB, and hedonic wellbeing. While activities related to both are shown to be important for ‘flourishers’, it’s interesting to note that even having the intention to pursue both may impact on our wellbeing (Huta & Ryan, 2010).

That is, out of four groups (hedonic motives only, eudaimonic motives only, both, or no motives at all):

“…individuals with both high hedonic and high eudaimonic motives—as compared to individuals in the other three groups—had the most favorable outcomes on vitality, awe, inspiration, transcendence, positive affect and meaning…”

The specific eudaimonic activities they assessed were (Huta & Ryan, 2010):

- Seeking to pursue excellence or a personal ideal;

- Seeking to do what you believe in;

- Seeking to use the best in yourself; and

- Seeking to develop a skill, learn, or gain insight into something.

Daily Activities and Behaviors

In another ‘daily diary’ study by Steger and colleagues (2008: 29), the following ‘eudaimonic behaviors’ were used to assess wellbeing:

- Volunteering one’s time;

- Giving money to someone in need;

- Writing out one’s future goals;

- Expressing gratitude for another’s actions, either written or verbal;

- Carefully listening to another’s point of view;

- Confiding in someone about something that is of personal importance; and

- Persevering at valued goals in spite of obstacles.

These eudaimonic activities were more strongly correlated than daily hedonic activities with wellbeing in terms of ‘daily meaning in life’ that the participants felt. The same went for daily positive affect and daily life satisfaction (Steger et al., 2008).

How Can One Best Practice Virtue?

By choosing the ‘golden mean’, to be succinct. Above, I introduced the ideas of excess and scarcity using an example of courage. For Plato, that meant pursuing knowledge as well as the other virtues of temperance, courage, and justice. To practice this pursuit, we need to exercise self-regulation and rational thought (Kraut, 2018).

Here is a larger table that goes much further than Plato’s original four virtues (Papouli, 2018). This gives some good examples of how this virtuous mean, between excess and deficiency, can be achieved.

Eudaimonic vs Hedonic: What’s the Difference?

The distinction between eudaimonia and hedonia is examined in great depth by Huta and Waterman in their 2013 review of the happiness literature. For those after a quick, broad distinction between the two, here are the authors’ given examples of eudaimonia, based on literature review:

- authenticity;

- excellence;

- meaning; and

- growth.

Contrast and compare these with their examples of hedonia, and you’ll see that very, very roughly, the second is much less value-laden and somewhat more experiential:

- an absence of distress;

- comfort;

- enjoyment; and

- pleasure.

Diving a bit deeper into things (quite a bit deeper), they highlight several points that remain unresolved. These include the fact that different definitions tend to be applied depending on whether researchers are examining the concepts at the ‘state’ or ‘trait’ level. Here, too, there are further differences depending on whether a philosophical or psychological standpoint is being adopted.

Long story short, there is no one definition for eudaimonia, but according to Huta & Waterman (2013: 1448),

“…the most common elements in definitions of eudaimonia are growth, authenticity, meaning, and excellence. Together, these concepts provide a reasonable idea of what the majority of researchers mean by eudaimonia.”

With regard to hedonia, while ‘absence of distress’ wasn’t always an important element,

“…there is a clear consensus that pleasure/enjoyment/life satisfaction is core to the definition”

(Huta & Waterman, 2013: 1448).

If you are interested in reading their systematic review, head over to their Research Gate article.

The Eudaimonia Institute

The Eudaimonia Institute is a Salem, North Carolina-based community of scholars. Dedicated to research on eudaimonia, the Institute’s mission is to promote cross-sectoral understandings of the phenomenon.

Through greater understanding of the concept itself, and the macro-environmental factors that promote it, the EI takes both an analytical and ‘systems’ view of eudaimonia.

But what does that mean in practice?

For Researchers

The EI hosts colloquia, conferences, and hosts lectures, albeit sporadically, according to their website. There is also an opportunity for interested researchers to submit grant applications, and it is possible to apply for a Visiting Research Scholar role.

For the Public

For you, me, and everybody else interested in human flourishing, the Wake Forest University Institute provides conference, research, and employment opportunities. It also has a Research Nexus on the website that offers key examples of interdisciplinary research on the topic.

Here, and in the EI News and Events section, expect to find relevant articles that are related to the Institute’s aims.

These include:

- What eudaimonia is – not just to philosophers or psychologists, but to communities, organizations, and educators;

- Measurement of the concept, assessment, and definitions from different fields;

- How organizations, business, and commercial enterprises can (and if they should) promote its prevalence; and

- How government, fiscal, and economic policies encourage or discourage eudaimonia in society, education, and communities.

5 YouTube Videos

You can pick any of these great videos to gain an even greater understanding of eudaimonia.

1. Aristotle & Virtue Theory: Crash Course Philosophy #38

As the title suggests, this is a short, ‘crash-course’ in Aristotlean ethics. Seven minutes, to be precise, and yet somehow quite a thorough overview of what eudaimonia is and is not.

2. A Recipe for Eudaimonia | Jay Kannaiyan | TEDxGurugram

Cleantech entrepreneur Jay Kannaiyan discusses his own interpretation of eudaimonia and his pursuit of the same. His own personal experience involved leaving a corporate job to embark on his own motorcycle journey in search of eudaimonia.

3. What is success? The Eudaimonia perspective | Christina Garidi | TEDxDrapanosWomen

Christina Garidi is the Founder of Eudaimonia Coaching UK, a coaching approach for professionals, businesses, and individuals. This TEDx Talk is more about her personal experience with eudaimonia. She talks about finding her purpose, redefining her understanding of success, and aligning the two.

4. PNTV: The Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle

“The word [Eudaimonia], which we commonly translate to mean happiness, actually means much more”.

Opening with this as an introduction, the video looks at five concepts – eudaimonia, arête, the Olympics, the mean, and magnanimity. A good combination of doctrines and examples to provide more context to the eudaimonia concept.

5. King’s College London: History of Philosophy’s Greatest Hits: Aristotle

In case you missed this video earlier, Professor Peter Adamson gives great examples of how Aristotle’s ‘golden mean’ concept both works and doesn’t always work. He suggests that rather than attempting to tell us how to live a life of virtue, Aristotle simply describes what this looks like. Clear, easy to follow, and potentially an “Aha” moment kind of video that really explains these ideas—and the philosopher’s approach, in brief.

3 Recommended Books

If reading appeals to you more, here are three books on the topic.

1. The Handbook of Eudaimonic Well Being (International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life) – Joar Vitterso

The Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being is edited by Dr. Joar Vittersø, a psychology professor with a social psychology Ph.D. from Oslo University. This compiles theory and empirical findings from researchers and academics from both historical and philosophical perspectives.

It provides different insights as well as considering the criticisms of wellbeing and eudaimonia.

Find the book on Amazon.

2. Happiness for Humans: Daniel C. Russell

University of Arizona Professor Daniel Russell presents an in-depth look at how classic Stoic and Aristotlean eudaimonism, have implications in the modern world.

Professor Russell’s main premise is that happiness is about having a life of activity. He considers what this could mean for contemporary politics and business, amongst other things.

Find the book on Amazon.

3. Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life – Edith Hall

Edith Hall argues along similar lines to Professor Adamson, who we mentioned earlier.

That is, rather than layout rules for how to be happy, Aristotle was a thinker who described. And he led by example. Aristotle’s Way considers how we can ‘engage with the texture of existence’, and live in accordance with virtues.

The book itself is laid out across ten practical lessons that, essentially, discuss what it means to be happy and human in our modern world.

Find the book on Amazon.

7 Quotes on the Topic

Happiness then, is found to be something perfect and self-sufficient, being the end to which our actions are directed.

Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics

No one does evil willingly.

Socrates

Virtue of character is a mean … between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency.

Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics

Fame is not the glory! Virtue is the goal, and fame only a messenger, to bring more to the fold.

Vanna Bonta

Courage is the most important of all the virtues because, without courage, you can’t practice any other virtue consistently.

Maya Angelou

You have to choose the best, every day, without compromise…guided by your own virtue and highest ambition.

Phillipa Gregory

Justice is the only virtue that seems to be another person’s good.

Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics

A Take-Home Message

Have you heard of eudaimonia before this article? If you did, we would love to hear about your experience, in particular, whether you first came across the topic from a philosophical or psychological angle.

What do you think of its potential applications for wellbeing, and of the QEWB scale?

Or, perhaps on a more practical note, have you got something to share about how policies might promote eudaimonia?

Let us know in the comments!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free.

- Annas, J. (1993). The morality of happiness. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- Bauer, J. J., McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2008). Narrative identity and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 81-104.

- Bhandari, D. R. (1998). Plato’s concept of justice: An analysis. Ancient Philosophy. Retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Anci/AnciBhan.htm

- Bobonich, C. (2010). Socrates and Eudaimonia. In Morrison, D.R. (2010). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press, p.293.

- Brown, E. (2012). Eudaimonia in Plato’s Republic. Retrieved from https://pages.wustl.edu/files/pages/imce/ericbrown/eudaimoniarepublic.pdf

- Chen, F. F., Jing, Y., Hayes, A., & Lee, J. M. (2013). Two concepts or two approaches? A bifactor analysis of psychological and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1033-1068.

- Cooper, J. (1997). Plato: Complete Works. Hackett.

- Curzer, H. J. (1991). The Supremely Happy Life in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Apeiron, 24(1), 47-70.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1-11.

- Gåvertsson, F. (n.d.). Eudaimonism: A Brief Conceptual History. Retrieved from https://www.fil.lu.se/media/utbildning/dokument/kurser/FPRK01/20131/Eudaimonism_abrief_conceptual_history.pdf

- Heintzelman, S. J. (2018). Eudaimonia in the contemporary science of subjective well-being: Psychological well-being, self-determination, and meaning in life. In E. Diener, E. Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (editors), Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

- Hursthouse, R. (1999). On Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huta, V., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 735–762.

- Huta, V., & Waterman, A. S. (2014). Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1425-1456.

- Irwin, T. H. (2012). Conceptions of happiness in the Nicomachean Ethics. In Shields, C. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Aristotle. Oxford University Press.

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207-222.

- Kings College London. (2012). King’s College London: History of Philosophy’s Greatest Hits: Aristotle. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s7xKzUxGBKA

- Kraut, R. (2018). ‘Aristotle’s Ethics’ in Zalta, E. N. (editor) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/aristotle-ethics/.

- Niemiec, C. P. (2014). Eudaimonic Well-Being. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, 2004-2005. Springer Dordrecht.

- Nothingistic.org. (2019). Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Book 1, Chapter 8. Retrieved from http://nothingistic.org/library/aristotle/nicomachean/nicomachean05.html

- Nothingistic.org. (2019). Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Book 1, Chapter 10. Retrieved from http://nothingistic.org/library/aristotle/nicomachean/nicomachean06.html

- Oxford Dictionaries. (2019). The language of Philip Pullman’s ‘His Dark Materials’. Retrieved from https://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2015/05/20/philip-pullman-language-his-dark-materials/

- Papouli, E. (2018). Aristotle’s virtue ethics as a conceptual framework for the study and practice of social work in modern times. European Journal of Social Work, April, 1-14.

- Price, A. W. (2011). Virtue and reason in Plato and Aristotle. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13-39.

- Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H., Westerhof, G. J., De Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., Walburg, A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of happiness studies, 17(4), 1351-1370.

- Sheldon, K.M. (2002). The self-concordance model of healthy goal striving: When personal goals correctly represent the person. In E.L. Deci, & R.M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 65–86). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(31), 8148-8156.

- Waterman, A.S. (1990a). Personal expressiveness: Philosophical and psychological foundations. Journal of Mind and Behavior, 11, 47–74.

- Waterman, A.S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaemonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678-691.

- Waterman, A.S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 234–252.

- Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., & Conti, R. (2008). The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 41-79.

- Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Bede Agocha, V., Kim, S.Y., & Brent Donnellan, M. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41-61.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Hello,

I absolutely loved the golden mean you have achieved with this work…. very informative and beautifully and clearly expressed.

I came across your article when I was trying to write a speech for my college’s golden jubilee and I thought about human flourishing.I do not come from an academic background in Philosophy or Psychology…. but then what are our lived lives ….just an amalgamation of the two.Thank you for the effort you have put in to help readers understand and really make us think , reflect and dig deeper.

Please keep writing more!

Excellent Article, Excellent Blog , Excellent Site ✅✅✅

BEN FATTO! Complimenti: molto interessante e svolto eccellenteMENTE Thank you Grazie Merci

Greetings to all.. In my field of work, I deal with university students and I deal flexibly in the interpretation of psychology, mental health and most of life’s problems. College students tend to explain more about flexible behavior, positive emotions, how to prevent mental illness, as well as the issue of psychological well-being. In our country we lack psychological well-being, but we make it for life and the continuity of life for the next generation, I loved your opinions.

I’ve been battling with a philosophical idea that will go in line with showing concern to others during this COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and social isolation. In my search, I came across this word, Eudaimonia, and it captures my interest. I decided to read further in this article and I am really glad I did got what I want… Exploring the altruistic eudaimonia as a concept of showing concern towards others during a pandemic. Thank you, Dr. Catherine. I am really grateful.

Very educational, informing article!

A novel procedure for sustaining positive arousal and pleasure (or ‘eudaimonia’), refutable with one swift kick

The ideal for any scientist with a great idea is to be able to explain it in a minute, and to confirm or falsify it as quickly. The world record for this arguably goes to the English philosopher Samuel Johnson, who rejected Archbishop Berkeley’s argument that material things only exist in one’s mind by striking his foot against a large stone while proclaiming, “I refute it thusly!”

Here is a similarly novel and useful idea that can be confirmed or refuted with a proverbial large kick, and can also be easily explained through affective neuroscience.

Fun Fact:

When we are concurrently perceiving some activity that has a variable and unexpected rate of reward while consuming something pleasurable, opioid activity increases and with it a higher sense of pleasure. In other words, popcorn tastes better when we are watching an exciting movie than when we are watching paint dry. The same effect occurs when we are performing highly variable or meaningful activity (creating art, doing good deeds, doing productive work) while in a pleasurable relaxed state. (Meaning would be defined as behavior that has branching novel positive implications). This is commonly referred to as ‘flow’ or ‘peak’ experience.

So why does this occur?

Dopamine-Opioid interactions: or the fact that dopamine activity (elicited by positive novel events, and responsible for a state of arousal, but not pleasure) interacts with our pleasures (as reflected by mid brain opioid systems), and can actually stimulate opioid release, which is reflected in self-reports of greater pleasure.

Proof (or kicking the stone):

Just get relaxed using a relaxation protocol such as progressive muscle relaxation, eyes closed rest, or mindfulness, and then follow it by exclusively attending to or performing meaningful activity, and avoiding all meaningless activity or ‘distraction’. Keep it up and you will not only stay relaxed, but continue so with a greater sense of wellbeing or pleasure. (In other words, this is a procedural bridge between mindful and ‘flow’ experiences that are not unique psychological ‘states’, but merely represent special aspects of resting states.)

Implications for meditation and stress management:

Sustained meaningful activity or the anticipation of acting meaningfully during resting states increases the affective ‘tone’ or value of that behavior, thus making productive work ‘autotelic’, or rewarding in itself.

Hi Art,

Thank you for your thoughts here. We’re pleased that our post inspired such an in-depth response. Unfortunately, in the interest of keeping our comment section easy for our readers to navigate, we could not publish your full comment. But thank you, and we welcome more succinct contributions in the future.

– Nicole | Community Manager

I became acquainted with eudaemonia when reading Hannah Arendt’s book The Human Condition; in conjunction with my study for a presentation on the first Chapter of Thoreau’s Walden that is entitled Economy. It seems plausible that Thoreau was on his own quest to flourish and have his sense of well-being. At any rate, I am thankful for having come upon this interesting article which you have shared. Thank you,

Thanks for the lovely introduction to eudaimonia. I have not heard the concept before, but reading about it I see connections to some other concepts that I was interested in, especially logotherapy proposed by Viktor Frankl. It is indeed the sense of meaning that makes life seem especially worth living.

I think in the modern world where more people are moving to urban areas, where living expense is high and pressure to make a living is greater, meaning has become somewhat of a luxury. Hedonic pleasure like consumerist shopping or dining are more immediate and accessible, whereas eudaimonic well-being requires more consistent investment of time and effort. I wonder whether affordable housing, higher minimal income/lower income equality can facilitate more space for people to thrive towards eudaimonic self-actualization.