What is Emotional Intelligence? +23 Ways To Improve It

We all have days when emotions get the better of us. Passion can cloud our judgment, fear can tyrannize our decisions, and resentment can lead us to do things we regret.

We all have days when emotions get the better of us. Passion can cloud our judgment, fear can tyrannize our decisions, and resentment can lead us to do things we regret.

But although emotionality has historically been portrayed as the fiery and foolish nemesis of reason and rationality, emotions are fundamental to our ability to function. They motivate us to act, are essential to social interactions, and form the bedrock of our felt sense of morality.

Emotional intelligence can provide a significant advantage for mastering our emotions. In this post, we’ll get up close with emotional intelligence to find out what it is, why it’s valuable, and how you can cultivate more of it.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will not only enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions, but also give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What Is Emotional Intelligence? 3 Examples

Many people have an intuitive grasp of what emotional intelligence is, but for academics, emotional intelligence (EQ or EI) has been a notoriously tricky construct to agree on.

Peter Salovey and John Mayer (1990, p. 185) were the first to develop a psychological theory of emotional intelligence and introduced EQ as a:

“set of skills hypothesized to contribute to the accurate appraisal and expression of emotion in oneself and others, the effective regulation of emotion in self and others, and the use of feelings to motivate, plan, and achieve in one’s life.”

From this perspective, emotional intelligence could be useful in almost all areas of life. Let’s look at some examples of emotional intelligence in action.

Self-awareness and leadership

Our awareness of emotions is centrally important to our relationships (Schutte et al., 2001) and ability to lead others (Rosete & Ciarrochi, 2005).

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has been praised globally for her ability to listen, show empathy, and connect with people in a crisis. CEO Today Magazine says we can learn a lot from Ardern’s ability to manage her own emotions effectively, as “self-awareness is the foundation on which all else is built” and “allows us to engage others on their terms” (Lothian, 2020).

Decision making

Psychologist and EQ expert Daniel Goleman (2019) recommends listening to your gut, as bodily intuitions reveal “decision rules that the mind gathers unconsciously.” In this way, emotional signals from our bodies provide a sort of intangible wisdom guiding us toward the “right” decisions.

To support this, Seo and Barrett (2007) found that stock investors who were experiencing more intense emotions and better at discriminating between emotions showed better decision-making performance. The researchers suggested that a greater awareness of emotions boosted the investors’ ability to manage emotional biases, which ultimately led to better decisions.

Stress management and mental wellbeing

Having an awareness of and ability to manage emotions can make us feel more equipped to deal with difficult feelings and situations (Gohm, Corser, & Dalsky, 2005), and support greater mental wellbeing (Fernandez-Berrocal, Alcaide, Extremera, & Pizarro, 2006).

Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, has spoken publicly about his struggles with mental health that ultimately led him to seek therapy. CNN Health highlighted how Prince Harry’s openness to talk about and express his emotions is helping others too, by making mental wellbeing a more acceptable topic to talk about, particularly for men (Duffy, 2021).

Emotional intelligence and personality

There’s been some controversy around using the term emotional ‘intelligence’ in models of EQ that include constructs resembling personality and broader social skills. Where do these attributes end and EQ begin (Neubauer & Freudenthaler, 2005)?

While more objective performance measures of EQ (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) have shown to be distinct from the Big Five personality traits of extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism, some self-report measures of EQ have shown greater crossover with personality measures (Brackett & Mayer, 2003).

Ability measures and self-report measures have shown a weak correlation with each other, suggesting that they may capture different aspects of EQ (Brackett & Mayer, 2003).

3 Fascinating Components and Theories of EQ

Mayer and Salovey’s integrative emotional intelligence model

Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) integrative model comprises four interconnected emotional abilities:

- Perception and expression of emotion

Noticing your own emotions and picking up on the emotions of others as well as the ability to distinguish between discrete emotions. - Using emotion to facilitate thought

How you incorporate emotions into your thinking processes and an understanding of when and how emotions can be helpful for reasoning processes. - Understanding and analyzing emotions

The capacity to decode emotions, make sense of their meaning, and understand how they relate to each other and change over time. - Reflective regulation of emotion

An openness to all emotions and the ability to regulate your own emotions and the emotions of others to facilitate growth and insight.

Bar-On’s model of social and emotional intelligence

Bar-On’s (1997, 2006) mixed model claims that EQ is a combination of competencies, skills, and “facilitators” that contribute to how people express themselves, respond to challenges in their environment, and connect with others.

Bar-On (2006) suggests that 10 distinct components provide the scaffolding of emotionally and socially intelligent behaviors:

- Self-regard

- Emotional awareness

- Assertiveness

- Empathy

- Interpersonal relationships

- Stress tolerance

- Impulse control

- Reality testing

- Flexibility

- Problem solving

Self-actualization, independence, social responsibility, optimism, and happiness were originally considered to be components of EQ but were later reframed as “facilitators” of EQ (Bar-On, 2006).

Daniel Goleman’s theory of EQ

Daniel Goleman (1995) popularized the concept of emotional intelligence in his widely acclaimed book Emotional Intelligence. Check out his TED talk on the art of managing emotions.

Goleman (1995, p. xii) offers a broad conceptualization of EQ abilities, including “self-control, zeal and persistence, and the ability to motivate oneself.” Goleman (2001) proposed that EQ provides a sign of an individual’s “potential” for developing emotional competencies (i.e., practical skills) that can help them thrive at work.

His original theory mapped emotional intelligence into five key domains:

- Knowing your emotions

- Managing emotions

- Motivating oneself

- Recognizing emotions in others

- Handling relationships

Why Is Emotional Intelligence Important?

Emotional intelligence is widely celebrated as a valuable commodity because it can predict life outcomes we care about, such as academic performance (MacCann et al., 2020), psychological adjustment (Fernandez-Berrocal et al., 2006), and workplace success (Lopes, Grewal, Kadis, Gall, & Salovey, 2006b).

Is EQ important in the workplace?

Lopes, Côté, and Salovey (2006a) suggest that a greater ability to manage emotions can benefit work performance in many ways. Using emotional intelligence in the workplace can improve decision making, help social interactions run smoothly, and enhance employees’ ability to deal with stressful times.

EQ has been linked to better task performance, organizational citizenship behaviors of employees (Côté & Miners, 2006), higher company rank, and higher scores of stress tolerance and interpersonal facilitation (e.g., positive interaction) as rated by peers and/or supervisors (Lopes et al., 2006b).

A meta-analysis involving 43 EQ studies concluded that ability measures, mixed models, and self-report and peer measures of EQ were all equally good at predicting job performance (O’Boyle, Humphrey, Pollack, Hawver, & Story 2011).

The importance of EI in leadership

Being a leader is a tough job that is likely to be harder if you have trouble managing your own emotions or the emotions of those you lead.

EQ has been found to predict leadership effectiveness even when accounting for IQ and personality (Rosete & Ciarrochi, 2005). In addition, Gardner and Stough (2002) found that emotional intelligence, particularly understanding and managing emotions, was strongly related to (positive) transformational leadership behaviors of senior managers.

Can EI be taught and learned?

Considering the many advantages EQ can bring, it’s not surprising that the popularity of EQ training has boomed over the last decade.

Remarkably, one study found that only 10 hours of group EQ training (lectures, role-play, group discussions, partner work, readings, and journaling) significantly improved people’s ability to identify and manage their emotions, and these benefits were sustained six months later (Nelis, Quoidbach, Mikolajczak, & Hansenne, 2009).

It’s clear that putting EQ skills into practice plays an important role in developing emotional intelligence. So, if you’re looking to teach EQ skills, Cherniss, Goleman, Emmerling, Cowan, and Adler (1988) suggest distinguishing between:

- Cognitive learning — Intellectually grasping the concept of how to improve emotional abilities. In other words, you may know that you need to bring your awareness to your emotions more often, but this doesn’t mean you’ll be able to.

- Emotional learning — Unlearning old habits and relearning more adaptive ones. To grow emotionally, we need to cut ties with our default ways of responding. If your old habit is withdrawing from your loved ones when you’re overwhelmed, a new habit could be reaching out to others when you’re stressed rather than closing off.

Training and Fostering EI Skills

- Recognize and name your emotions.

Taking the time to notice and label your feelings can help you choose the best way to respond to situations. - Ask for feedback.

Even though it might make you cringe, it’s helpful to get others’ viewpoints on your emotional intelligence. Ask people how they think you handle tricky situations and respond to the emotions of others. - Read literature.

Reading books from someone else’s perspective could deepen your understanding of their inner worlds and boost social awareness in the process.

MindTools (n.d.) has also helpfully laid out six ways you can enhance emotional intelligence with a little self-reflection and honesty:

- Notice how you respond to people — Are you being judgmental or biased in your assessments of others?

- Practice humility — Being humble about your achievements means you can acknowledge your successes without needing to shout about them.

- Be honest with yourself about your strengths and vulnerabilities and consider development opportunities.

- Think about how you deal with stressful events — Do you seek to blame others? Can you keep your emotions in check?

- Take responsibility for your actions and apologize when you need to.

- Consider how your choices can affect others — Try to imagine how they might feel before you do something that could affect them.

World-renowned personal coach, entrepreneur, and business strategist Tony Robbins (n.d.) has outlined his six tips for growing emotional intelligence:

- Identify what you’re feeling. Use mindfulness to routinely check in on your feelings from a more neutral perspective.

- Acknowledge and appreciate your emotions for what they are. Robbins (n.d.) emphasizes that “emotions are never wrong. They are there to support you.”

- Be curious about what an emotion is trying to tell you.

- Tap into your inner confidence to deal with emotions by remembering when you’ve done this effectively in the past.

- Mentally think through how you would deal with difficult feelings in the future to feel more equipped when the time comes.

- With a renewed confidence in your EQ, Robbins suggests getting excited to use these skills to achieve your goals and enhance your relationships with others.

Want more tips on how to foster EQ? Ramona Hacker gives a rundown of her six steps to improve emotional intelligence in this TED talk, which she developed through her personal EQ journey.

If you’re serious about EQ training to help clients or organizations, check out our in-depth article on How to Improve Emotional Intelligence Through Training.

How to Measure EQ: 3 Reliable Tests

Below we’ve listed three of the most well-known and reliable EQ tests available.

Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) 2.0

The MSCEIT 2.0 (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002; Mayer, Caruso, Salovey, & Sitarenios, 2003) is a 141-item test capturing abilities across their four core domains of EI:

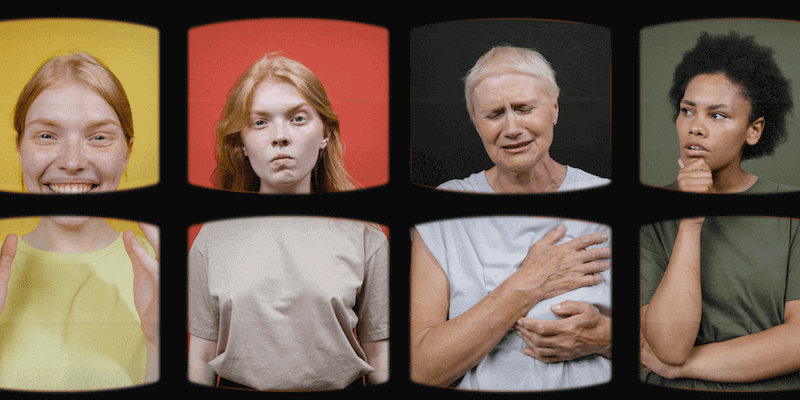

- Perceiving emotion

Tasks ask people to rate how much a specific emotion is expressed on someone’s facial expression, in a design, or a landscape. - Using emotions in thought

People are asked to rate which emotions would be useful in certain situations and to identify different sensations that match specific feelings. - Understanding emotion

Tasks evaluate emotional understanding, such as knowing how different emotions can be combined to make other emotions and how emotions can evolve with time. - Managing emotion

In hypothetical scenarios, people are tasked with rating the best way to achieve a particular emotional outcome and also to decide the actions that would be most effective to manage someone else’s feelings.

You can order copies of the MSCEIT from the publisher, Multi-Health Systems Inc.

The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i)

The EQ-i is a 133-item self-report scale developed alongside Bar-On’s (1997) model of emotional and social intelligence.

People rate the extent to which a short description is very seldom true of them (1) or very often true of them (5), and higher scores are associated with more effective emotional and social functioning (Bar-On, 1997).

Sub-scales of the EQ-i are grouped within these five scales:

- Intrapersonal EQ:

- Self-regard

- Emotional awareness

- Assertiveness

- Self-actualization

- Independence

- Interpersonal EQ:

- Empathy

- Interpersonal relationships

- Social responsibility

- Adaptability:

- Problem solving

- Reality testing

- Flexibility

- Stress management:

- Stress tolerance

- Impulse control

- General mood:

- Happiness

- Optimism

A total EQ score can be calculated as well as composite scores for each of the five scales. The EQ-i 2.0 is a more recently released version of the EQ-i you can purchase.

Self-Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SREIT)

This 33-item scale developed by Schutte et al. (1998) was based on Salovey and Mayer’s (1990) EQ model, with the aim of creating an empirically sound self-report measure of people’s current level of emotional intelligence.

The scale captures self-reported EQ across three categories:

- Appraisal and expression of emotion (self and others)

- Regulation of emotion (self and others)

- Using emotions to solve problems

The SREIT asks people to rate how much they agree that items are characteristic of them, such as “Other people find it easy to confide in me” or “I like to share my emotions with others.” The good news is, the authors of the SREIT have made their scale freely available for clinical and research purposes, and it can be found in their original paper (Schutte et al., 1998).

If you’d like to explore a larger range of assessments and tests, we listed 17 different types of emotional intelligence tests here.

Want to learn even more about EQ assessment? Then read our article on Assessing Emotional Intelligence Scales.

3 Best Books on the Topic

To enhance your EQ prowess even further, here are three more great reads, which could help you understand and harness your emotions for the betterment of yourself and others:

- Dare to Lead by Brené Brown

- How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett

- Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help Our Kids, Ourselves, and Our Society Thrive by Marc Brackett

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

If you want to apply what you know about emotional intelligence, we’ve got you covered. In our Positive Psychology Toolkit© we have over 400 tools. Many of these are useful for the development of EQ, for example:

- Building Emotional Awareness:

This is a 10- to 40-minute meditation exercise. Meditation exercises can be helpful for EQ because being mindful of emotions facilitates understanding and insight into emotional experiences. - Reading Facial Expressions of Emotions:

This is a fun 15-minute group task to develop an awareness of facial expressions. - Self-Reflecting on Emotional Intelligence:

This short exercise considers the four components of EQ. - Telling an Empathy Story:

This free resource – Telling an Empathy Story – is a group exercise encouraging the development of empathy, which is a integral part of emotional development. - Emotional Intelligence Masterclass©:

This Masterclass is the ultimate resource for enhancing your clients’ or your own emotional intelligence. Highly recommended with several five-star reviews, this is a thoroughly researched and practical approach to enhancing EQ. - 17 Emotional Intelligence Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop emotional intelligence, this collection contains 17 validated EI tools for practitioners. Use them to help others understand and use their emotions to their advantage.

A Take-Home Message

Plato was definitely onto something when he said “Human behavior flows from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge” (BrainyQuote, n.d.).

Emotions can be a valuable source of knowledge. As we’ve seen in this post, emotional intelligence could facilitate positive decisions and behaviors that help us realize success in our relationships, mental wellbeing, and work aspirations.

If you want to develop your EQ, there’s an abundance of simple ways you can begin building your emotional awareness today. If you’re supporting others to cultivate their EQ, both cognitive and emotional forms of learning are likely to be important (Cherniss et al., 1988). In addition to knowing what emotional intelligence is and how to get more of it “in theory,” EQ needs to be put into practice to grow.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free.

- Bar-On, R. (1997). The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems.

- Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18(suppl.), 13–25.

- Brackett, M. A., Mayer, J. D. (2003). Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1147–1158.

- BrainyQuote (n.d.). Plato quotes. (n.d.). Retrieved May 30, 2021, from https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/plato_384673#

- Cherniss, C., Goleman, D., Emmerling, R., Cowan, K., & Adler, M. (1998). Bringing emotional intelligence to the workplace: A technical report issued by the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations.

- Côté, S., & Miners, C. T. (2006). Emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence, and job performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(1), 1–28.

- Duffy, J. (2021, March 9). Prince Harry opens up: A role model for emotional availability in men and boys. CNN. Retrieved June 9, 2021, from https://edition.cnn.com/2021/03/09/health/mens-mental-health-prince-harry-wellness/index.html

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Alcaide, R., Extremera, N., & Pizarro, D. (2006). The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individual Differences Research, 4, 16–27.

- Gardner, L., & Stough, C. (2002). Examining the relationship between leadership and emotional intelligence in senior-level managers. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23, 68–78.

- Gohm, C. L., Corser, G. C., & Dalsky, D. J. (2005). Emotional intelligence under stress: Useful, unnecessary, or irrelevant? Personality and Individual Differences, 39(6), 1017–1028.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

- Goleman, D. (2001). An EI-based theory of performance. In C. Cherniss & D. Goleman (Eds.), The emotionally intelligent workplace: How to select for, measure, and improve emotional intelligence in individuals, groups, and organizations (pp. 27–44). Jossey-Bass.

- Goleman, D. (2019). Go with your gut: Emotional intelligence and decision making. Retrieved May 30, 2021, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/go-your-gut-emotional-intelligence-decision-making-daniel-goleman/

- Harvard Division of Continuing Education. (2019, August 26). How to improve your emotional intelligence. Harvard Professional Development. Retrieved May 30, 2021, from https://professional.dce.harvard.edu/blog/how-to-improve-your-emotional-intelligence/

- Lopes, P. N., Côté, S., & Salovey, P. (2006a). An ability model of emotional intelligence: Implications for assessment and training. In V. U. Druskat, G. Mount, & F. Sala (Eds.), Linking emotional intelligence and performance at work: Current research evidence with individuals and groups (pp. 53–80). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Lopes, P. N., Grewal, D., Kadis, J., Gall, M., & Salovey, P. (2006b). Evidence that emotional intelligence is related to job performance and affect and attitudes at work. Psicothema, 18, 132–138.

- Lothian, A. (2020, June 9). Jacinda Ardern: How great leaders manage a crisis. CEOToday Magazine. Retrieved May 30, 2021, from https://www.ceotodaymagazine.com/2020/06/jacinda-ardern-how-great-leaders-manage-a-crisis/

- MacCann, C., Jiang, Y., Brown, L. E., Double, K. S., Bucich, M., & Minbashian, A. (2020). Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146, 150–186.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2002). MSCEIT: Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Multi-Health Systems.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R., & Sitarenios, G. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion, 3(1), 97–105.

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. E. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3–31). Basic Books.

- MindTools (n.d.). Emotional intelligence: Developing strong “people skills”. Retrieved May 30, 2021, from https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newCDV_59.htm

- Nelis, D., Quoidbach, J., Mikolajczak, M., & Hansenne, M. (2009). Increasing emotional intelligence: (How) is it possible? Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 36–41.

- Neubauer, A. C., & Freudenthaler, H. H. (2005). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. Schultz & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), Emotional intelligence: an international handbook (pp. 31–50). Hogrefe.

- O’Boyle, E. H., Jr., Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., & Story, P. A. (2011). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 788–818.

- Robbins, T. (n.d.) Improve and develop emotional intelligence. Retrieved May 30, 2021, from https://www.tonyrobbins.com/personal-growth/how-to-improve-emotional-intelligence/

- Rosete, D., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Emotional intelligence and its relationship to workplace performance outcomes of leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(5), 388–399.

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211.

- Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Bobik, C., Coston, T. D., Greeson, C., Jedlicka, C., … Wendorf, G. (2001). Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. The Journal of Social Psychology, 141(4), 523–536.

- Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., & Dornheim, L. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 167–177.

- Seo, M., & Barrett, L. (2007). Being emotional during decision making—Good or bad? An empirical investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 923–940.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

As a professional psycho-spiritual therapist and counsellor (M.Art), though a beginner in the field, I am thrilled and edified by the organizational skill and thoughtfulness of PositivePsychology.com especially in bringing a lot of experts to write and address myriads of issues in our contemporary world. This article and like many others that I have read from your uploads have been very enriching, educating, stimulating and daring. Special thanks to all the contributing researchers, scholars and writers!

Thank you for the time and care that you put into writing this article. It’s been a very inspiring read.

This was very helpful

Leaves you going down a rabbit hole beyond the article, didn’t know the levels of EQ and how bottomless the idea of it is.

This is a Very informative and motivational article. I really respect and appreciate the “break downs”. How well presented it is.