What Is the Peak–End Rule? How to Use It Smartly

It’s not all bad. Sometimes we can use our leanings to make our lives easier and better.

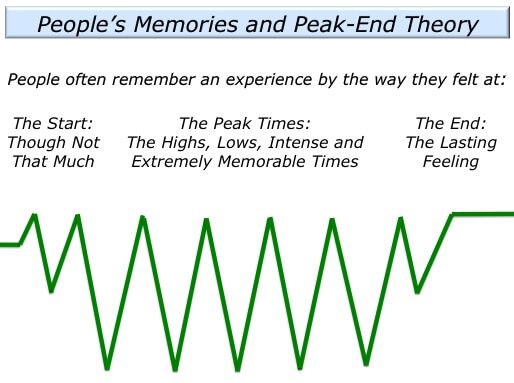

The peak–end rule refers to how we reflect on an experience — often a painful one — based on its most extreme point and its endpoint (Müller et al., 2019; Kahneman, 2012).

This article explores the peak–end rule — how mental shortcuts shape how we see what’s happened and how to use them to make difficult situations more manageable, and enjoyable ones even better.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Productivity Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients become more productive and efficient.

This Article Contains:

What Is the Peak–End Rule?

The peak–end rule states that when we look back at an event or experience, our recollections and opinions are heavily influenced by what happened at its peak intensity and its end (Alaybek et al., 2022).

Just think of a trip to IKEA. Our children remember the excitement of the ice cream just before they leave the shop more than the dull trek through furniture. The customer experience is shaped by the most intense point and its finish (Steenstra, 2021).

It often means we miss many of the positives that were present. Our recollection ignores much of the duration when our discomfort was minimal, and we home in on the most upsetting and stressful aspects of an episode.

Also referred to as the “peak–end memory bias,” it is an important area of psychological research with many applications, including education, product design, and, particularly, healthcare (Kahneman, 2012).

When we revisit something painful that has happened — perhaps a medical procedure or an operation — we evaluate it based on its worst point and its conclusion (Müller et al., 2019).

“The peak–end bias describes that retrospective evaluations are often dominated by the average discomfort of the worst and the final moments; these are labeled the peak and the end respectively” (Müller et al., 2019, p. 1).

Perhaps surprisingly, “the duration of the procedure had no effect whatsoever on the ratings of total pain” (Kahneman, 2012, p. 380). “Duration neglect,” as it is referred to, describes how the length of the experience is less important than the peak–end bias on retrospective evaluation (Müller et al., 2019).

2 Peak–End Rule Examples

As a result, we view the whole day negatively despite much of it potentially being a positive experience.

Let’s look in more detail at a few examples from Daniel Kahneman (2012), author of the international bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow,” psychologist, and recipient of the Nobel prize for his longtime research into judgment and decision-making.

A painful recollection

Two patients underwent the same procedure. It lasted eight minutes for patient A and 24 minutes for patient B. While both reported a similar pain level overall, the duration for patient B was three times as long (Kahneman, 2012).

Who had the worst recollection, patient A or patient B?

Surprisingly, it was patient A. Although their procedure was much shorter, they reported a higher degree of pain in the final minutes than patient B. Duration was not as important as the unpleasant memory of what happened at the end.

Kahneman’s example supports the peak–end rule. For patient B, “the longer experience is perceived as less painful even though it includes more pain in total, but ends with a period of less intense pain” (Müller et al., 2019, p. 2).

Our life story

Kahneman tells psychologist Ed Diener’s story about a fictitious character Jen to show how the peak–end rule can apply to a life narrative.

In the unfortunate story, Jen had no children, had not been married, and died instantly and painlessly in a made-up car accident (Kahneman, 2012).

But in one version of the story, she had earlier led a wonderful life, with many hobbies and friends, when she died. In the other, she had an extra five years before the fatal accident, yet they were less pleasant than her earlier years.

When participants in a study read both stories, they were asked two questions:

As a whole, how desirable was Jen’s life?

How much happiness or unhappiness did Jen experience in her life?

When the results came back, it surprised researchers to find that according to the participants, Jen’s extra five years of life led to a perceived drop in desirability and happiness. It seems that the longer duration had no effect. Instead, the slight decrease in perceived satisfaction in her final years resulted in her overall life being judged as less happy.

Whether we are judging minutes or a lifetime, it is the most extreme experience and how it ends that instinctively matters to us. We only tend to recall the highlights (Kahneman, 2012).

Daniel Kahneman & Peak–End Theory

Furthermore, the emotions experienced determine whether an individual will, going forward, attempt to avoid similar events and activities or seek them out. And our emotional recollection of that event is, according to Kahneman’s peak–end theory, associated with the most intense moment (or the peak) and the emotions related to its end (Strijbosch et al., 2019).

According to Kahneman (2012) — and based on his research and theoretical assumptions — the peak–end rule may result from evolutionary bias. He distinguishes between two aspects of the self.

The “experiencing self” goes through discomfort or pain at the time of the event. In contrast, the “remembering self” is “dominated by the most extreme moment of an experience,” influencing behavior and choices (Müller et al., 2019. p. 2). Its function, Kahneman says, is to help us avoid future moments that could result in post-traumatic stress.

Barbara Fredrickson (2000) included the endpoint of the experience in the peak–end theory as it determines the boundaries and thereby helps define the peak.

Research into peak–end theory shows that the effect goes beyond experiences of temporary pain; studies also show the bias creeps into other settings, including (Müller et al., 2019):

- Episodes of chronic pain

- How we interpret unpleasant sounds

- Poor picture quality while watching videos

- Feelings of breathlessness

- Degree of mental effort

And the peak–end theory extends beyond episodes of discomfort to include positive subjective experiences, such as enjoyment and pleasure (Kahneman, 2012).

For example, eating a preferred piece of food last during a meal improves the reflective experience (Müller et al., 2019). As a result, the dessert at the end of the meal could be significantly more important than the starter for the customer’s experience and, ultimately, their review.

As the peak–end theory is not as domain specific as first thought, understanding the process better can positively affect psychological treatments, such as how best to structure exposure sessions for helping clients with anxiety, panic attacks, and phobias (Müller et al., 2019).

Interesting Peak–End Studies

Research attempting to understand the peak–end rule more fully has been highly creative, including settings as diverse as the following:

- Horror movies: In this unusual study, participants watched scary movies. Half the group had the movie finish at the most frightening moment, while the others watched to the end.

Those in the former group reported significantly higher anxiety scores than those ending on a happier note. It seems our anxiety, like our pain, is impacted by the end of the experience and the feelings we are left with (Müller et al., 2019).

- Virtual reality: The effects of the peak–end rule, while highly generalizable, may not apply to less ecologically valid digital settings — in this case, virtual reality (VR).

In this study, researchers assigned each of the 40 students to one of two versions of a VR movie. In the second version, a pivotal scene was extended and made more emotionally intense to see if this led to stronger emotions and a change to the remembered experience. The results didn’t show any difference in the group, suggesting that the peak–end rule had not extended (in this case) to the digital setting (Strijbosch et al., 2019).

The peak–end theory continues to fascinate researchers, leading to ever more ingenious studies to test how far its predictive power extends and to what environments and settings (Alaybek et al., 2022).

How to Apply the Peak–End Rule

Recognizing that it is less about the entire experience and more about particular aspects, we can reframe or refocus our attention and thinking (Müller et al., 2019; The Decision Lab, n.d.; Kahneman, 2012).

- Create a strong peak

Ensure that the most intense peak in the experience is a positive one. Perhaps add in meaningful interactions, positive news, or something that increases positive emotions. - Finish on a high note

Plan for the final moments of an experience to be upbeat and leave a lasting impression. For example, ensure that the final stage of a medical procedure is less painful or that the wrapping up of a difficult meeting is encouraging. - Manage expectations

Make sure that people know what to expect. Early awareness and knowledge will limit the likelihood of disappointment or nasty surprises that finish engagement on a sour note. - Focus on the details

Think about what can be done to improve the atmosphere and environment. An event or experience could be scheduled earlier in the day rather than after lunch when people are tired. Rather than remaining seated, meetings and presentations could be based around movement, creating more engagement and high points.

We can apply the peak–end rule and theory to many aspects of work and customer engagement, including:

Application in UX design

Designers can take learnings from peak–end theory to make users’ experience of products more meaningful and relevant (The Decision Lab, n.d.).

User experience (UX) designers should pay particular attention to the most intense points of the user’s journey and its ending, ensuring that the UX is straightforward, helpful, valuable, and entertaining.

Usability testing can ensure the design matches the user’s needs, provide maximum positive experiences, and identify minor changes to improve the high points and the ending to create the most beneficial impact (Yablonski, 2020).

In customer service

When organizations and service providers understand the theory behind the peak–end rule, they can offer customers a more positive and memorable experience (The Decision Lab, n.d.).

To do so, they should make service interactions positive and memorable at the most intense times (such as when addressing an issue or actioning a sale) and at its conclusion.

Customer service agents should solve problems quickly and effectively. And interactions such as transactions should be performed with care and customers thanked, offering a consistent and friendly service (Okeke, 2019; Toporek, 2019).

In teaching and parenting

As a teacher, parent, or caregiver, it helps to identify and understand the peak moments in our children’s experiences. When do they happen? And why are they important (Kahneman, 2012)?

Once done, we can take steps to enhance them. This might include incorporating a memorable outing into the day or adding a special activity at the end of a lesson.

Such times can be the highlight of the child or young adult’s experience and will shape how they see their time with us and the scheduled activity, and leave a lasting and positive impact that helps to strengthen bonds with our children (Hoogerheide et al., 2017).

4 Videos Worth Watching

The following videos are four of our favorites, either directly exploring the peak–end rule or what affects our biased experience of the past and present.

The riddle of experience vs. memory

Daniel Kahneman expertly explores the pitfalls and opportunities for increasing happiness in ourselves and our clients based on our perception of our experiences.

Watch the video to gain a deeper understanding of the peak–end rule and hear his arguments for the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self.”

Thinking, Fast and Slow

In this video, Daniel Kahneman introduces us to several of the points covered in his book of the same name.

Listen to his fantastic explanation of the two systems involved in how we think and the faults and biases that result from their involvement in our decision-making and behavior.

The surprising habits of original thinkers

Author of several international bestsellers, organizational psychologist Adam Grant takes us on a tour of the habits of original thinkers.

While not explicitly covering the peak–end rule, it encourages us to challenge our thinking and the assumptions we make about ourselves and others. Many of these arise out of bias, and we can combat this by seeing things with fresh eyes — “vuja de,” as Grant calls it.

Positive emotions open our mind

Barbara Fredrickson (2000), one of the early researchers on the peak–end rule, has spent much of her career understanding the importance and effect of positive emotions, also captured in her excellent book Positivity: Groundbreaking Research to Release Your Inner Optimist.

Perhaps the most valuable takeaway from this video is Fredrickson’s explanation of her broaden-and-build theory. While it explains how experiencing one positive emotion influences having others, it also details how it broadens our repertoire for thinking and reacting.

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

We have many resources available for individuals wishing to address their biases and to support therapists in helping clients understand how they might reflect on their life’s narrative differently.

Two free resources include:

- Imagery-Based Exposure Worksheet

Difficult past events can lead to strong negative emotions. In this worksheet, clients reflect on events and feelings and practice sitting with their discomfort. - The What-If Bias

We often get stuck thinking about a situation’s bad or unwanted outcomes. This exercise encourages clients to consider the positives before a situation or event happens.

More extensive versions of the following tools are available with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit©, but they are described briefly below:

- Seeing Through the Hindsight Bias

We all experience disappointment and regret from time to time. Individuals experiencing depression, though, may exaggerate and prolong the negative feelings.

This exercise encourages clients to reflect on a past decision and consider what they could have done differently.

-

- Step one – Describe a personal situation.

- Step two – Consider why you made the decision you did.

- Step three – Reflect on what you knew at the time and the possible outcome.

- Step four – Look back on your decision with the knowledge you have now.

- Step five – Would you make the same decision today? If not, what would you do?

- Step six – Accept that decisions are based on what we know at the time and that we can learn from our previous mistakes.

- Increasing Awareness of Cognitive Distortions

Our thinking is often distorted — the result of biases or a lack of knowledge. This tool helps us become more aware of our distorted thinking before dismantling it.- Step one – Learn about the different kinds of cognitive distortions.

- Step two – Identify your personal distortions.

- Step three – Spend five to 10 minutes each day capturing them in the worksheet.

What could you do to reduce the effect of your cognitive distortions?

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others become more productive and efficient, this collection contains 17 validated productivity and work efficiency exercises. Use them to help others prioritize better, eliminate time wasters, maximize their personal energy, and more.

A Take-Home Message

As humans, we have the tendency to recall the highlights — or lowlights — of an experience.

Psychologists refer to this as the peak–end rule. We focus on the most intense aspect and endpoint of an experience and ignore everything else. The result is a biased and often incomplete recollection of what has happened that can impact our wellbeing (Kahneman, 2012).

Our retrospective evaluation ignores most of the duration when our discomfort was low, and we find ourselves dwelling on the most troubling and stressful aspects of an episode.

Research has proven the use of the peak–end rule in many different settings, as diverse as education, the workplace, healthcare, and relationships (Alaybek et al., 2022; Strijbosch et al., 2019).

As a result, we can use the theory and the associated learnings to modify activities, events, and interactions to improve individuals’ perceptions of their experience. This could be particularly helpful when managing painful or uncomfortable medical procedures or during upsetting and emotional therapeutic interventions.

While further research is required to fully understand the scope of the peak–end theory’s effect, undoubtedly, it has considerable value in designing future engagements and experiences in physical and mental health treatment.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Productivity Exercises for free.

- Alaybek, B., Dalal, R. S., Fyffe, S., Aitken, J. A., Zhou, Y., Qu, X., Roman, A., & Baines, J. I. (2022). All’s well that ends (and peaks) well? A meta-analysis of the peak–end rule and duration neglect. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 170, 104149.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: The importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 14(4), 577–606.

- Fredrickson, B. (2010). Positivity: Groundbreaking research reveals how to release your inner optimist and thrive. Oneworld.

- Hoogerheide, V., Vink, M., Finn, B., Raes, A. K., & Paas, F. (2017). How to bring the news … peak–end effects in children’s affective responses to peer assessments of their social behavior. Cognition and Emotion, 32(5), 1114–1121.

- Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin.

- Kahneman, D., & Riis, J. (2005). Living and thinking about it: Two perspectives on life. In F. A. Huppert, N. Baylis, & B. Keverne (Eds.) The Science of Well-Being (pp. 285–304). Oxford University Press.

- Müller, U. W., Witteman, C. L., Spijker, J., & Alpers, G. W. (2019). All’s bad that ends bad: There is a peak–end memory bias in anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

- Okeke, K. (2019, March 11). Understanding the peak–end rule & how it affects customer experience. Customer Think. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://customerthink.com/understanding-the-peak-end-rule-how-it-affects-customer-experience/.

- The Decision Lab. (n.d.). How do our memories differ from our experiences? Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/peak-end-rule.

- Steenstra, N. (2021, April 9). Hotdogs, ice cream, and the power of the peak–end rule. LinkedIn. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/hotdogs-ice-cream-power-peak-end-rule-nadine-steenstra/.

- Strijbosch, W., Mitas, O., van Gisbergen, M., Doicaru, M., Gelissen, J., & Bastiaansen, M. (2019). From experience to memory: On the robustness of the peak-and-end-rule for complex, heterogeneous experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

- Toporek, A. (2019, December 11). The peak–end rule and customer experience. CTS. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://customersthatstick.com/blog/customer-service-techniques/the-peak-end-rule-and-customer-experience/.

- Yablonski, J. (2020, May 19). Peak–end rule. UX Collective. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://uxdesign.cc/peak-end-rule-54eedd375c4d.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

This description of peak -end rule answers the question that led me to this article, as follows: “Why was our wonderful vacation of a lifetime so overshadowed and ruined by the violent car-wildlife collision that happened on the trip home?”

The event was shocking and dramatic, clearly the most emotionally intense event of the otherwise serene and peaceful vacation with my sister. And because it was a short distance from home on the final stretch of the journey, it was also the end.

I have been sad that most of the happy memories of the long-awaited and truly beautiful week have been virtually erased. As I try to relive the trip memories, all that replays is the harrowing crash at the trip’s end.

Thank you to the author and those who did the research for supplying a reason for the perception.

Hi Laurie,

I’m sorry to hear that your vacation was marred by such a distressing event! The peak-end rule does help explain why that incident looms so large in your memory.

Thank you for acknowledging the value of the research and its ability to provide some understanding, even if it can’t undo the emotional impact. I hope that with time, the happier moments of your trip can reclaim their rightful place in your memory.

Kind regards,

Julia | Community Manager

Thanks for capturing the literature so beautifully. It really has been a fascinating journey for me in terms of measuring happiness. Thanks for citing my work! Talya Miron-Shatz, PhD.

Loved this article, it makes total sense of how do we handle relationships in our life and the impact they leave on the way we lead our lives. Thanks, looking forward to many more.