Operant Conditioning Theory (+ How to Apply It in Your Life)

Operant conditioning is a well-known theory, but how do you put it into practice in your everyday life?

Operant conditioning is a well-known theory, but how do you put it into practice in your everyday life?

How do you use your knowledge of its principles to build, change, or break a habit? How do you use it to get your children to do what you ask them to do – the first time?

The study of behavior is fascinating and even more so when we can connect what is discovered about behavior with our lives outside of a lab setting.

Our goal is to do precisely that; but first, a historical recap is in order.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- Our Protagonists: Pavlov, Thorndike, Watson, and Skinner

- Operant Conditioning: A Definition

- The Principles of Operant Conditioning

- 10 Examples of Operant Conditioning

- Operant Conditioning vs. Classical Conditioning

- Operant Conditioning in Therapy

- Applications in Everyday Life

- A Look at Reinforcement Schedules

- Useful Techniques for Practitioners

- An Interesting Video

- 5 Books on the Topic

- A Take-Home Message

- References

Our Protagonists: Pavlov, Thorndike, Watson, and Skinner

Like all great stories, we will begin with the action that got everything else going. A long time ago, Pavlov was trying to figure out the mysteries surrounding salivation in dogs. He hypothesized that dogs salivate in response to the presentation of food. What he discovered set the stage for what was first called Pavlovian conditioning and later, classical conditioning.

What does this have to do with operant conditioning? Other behavior scientists found Pavlov’s work interesting but criticized it because of its focus on reflexive learning. It did not answer questions about how the environment might shape behavior.

E. L. Thorndike was a psychologist with a keen interest in education and learning. His theory of learning, called connectionism, dominated the United States educational system. In a nutshell, he believed that learning was the result of associations between sensory experiences and neural responses (Schunk, 2016, p. 74). When these associations happened, a behavior resulted.

Thorndike also established that learning is the result of a trial-and-error process. This process takes time, but no conscious thought. He studied and developed our initial concepts of operant conditioning reinforcement and how various types influence learning.

Thorndike’s principles of learning include:

- The Law of Exercise, which involves the Law of Use and the Law of Disuse. These explain how connections are strengthened or weakened based on their use/disuse.

- The Law of Effect focuses on the consequences of behavior. Behavior that leads to a reward is learned, but behavior that leads to a perceived punishment is not learned.

- The Law of Readiness is about preparedness. If an animal is ready to act and does so, then this is a reward, but if the animal is ready and unable to act, then this is a punishment.

- Associative shifting occurs when a response to a particular stimulus is eventually made to a different one.

- Identical elements affect the transfer of knowledge. The more similar the elements, the more likely the transfer because the responses are also very similar.

Later research did not support Thorndike’s Laws of Exercise and Effect, so he discarded them. Further study revealed that punishment does not necessarily weaken connections (Schunk, 2016, p. 77). The original response is not forgotten.

We all have experienced this at one time or another. You are speeding, get stopped, and receive a ticket. This suppresses your speeding behavior for a short time, but it does not prevent you from ever speeding again.

Later, John B. Watson, another behaviorist, emphasized a methodical, scientific approach to studying behavior and rejected any ideas about introspection. Behaviorists concern themselves with observable phenomena, so the study of inner thoughts and their supposed relationship to behavior was irrelevant.

The “Little Albert” experiment, immortalized in most psychology textbooks, involved conditioning a young boy to fear a white rat. Watson used classical conditioning to accomplish his goal. The boy’s fear of the white rat transferred to other animals with fur. From this, scientists reasoned that emotions could be conditioned (Stangor and Walinga, 2014).

In the 1930s, B. F. Skinner, who had become familiar with the work of these researchers and others, continued the exploration of how organisms learn. Skinner studied and developed the operant conditioning theory that is popular today.

After conducting several animal experiments, Skinner (1938) published his first book, The Behavior of Organisms. In the 1991 edition, he wrote a preface to the seventh printing, reaffirming his position regarding stimulus/response research and introspection:

“… there is no need to appeal to an inner apparatus, whether mental, physiological, or conceptual.”

From his perspective, observable behaviors from the interplay of a stimulus, response, reinforcers, and the deprivation associated with the reinforcer are the only elements that need to be studied to understand human behavior. He called these contingencies and said that they “account for attending, remembering, learning, forgetting, generalizing, abstracting, and many other so-called cognitive processes.”

Skinner believed that determining the causes of behavior is the most important factor for understanding why an organism behaves in a particular way.

Schunk (2016, p. 88) notes that Skinner’s learning theories have been discredited by more current ones that consider higher order and more complex forms of learning. Operant conditioning theory does not do this, but it is still useful in many educational environments and the study of gamification.

Now that we have a solid understanding of why and how the leading behaviorists discovered and developed their ideas, we can focus our attention on how to use operant conditioning in our everyday lives. First, though, we need to define what we mean by “operant conditioning.”

Operant Conditioning: A Definition

The basic concept behind operant conditioning is that a stimulus (antecedent) leads to a behavior, which then leads to a consequence. This form of conditioning involves reinforcers, both positive and negative, as well as primary, secondary, and generalized.

- Primary reinforcers are things like food, shelter, and water.

- Secondary reinforcers are stimuli that get conditioned because of their association with a primary reinforcer.

- Generalized reinforcers occur when a secondary reinforcer pairs with more than one primary reinforcer. For example, working for money can increase a person’s ability to buy a variety of things (TVs, cars, a house, etc.)

The behavior is the operant. The relationship between the discriminative stimulus, response, and reinforcer is what influences the likelihood of a behavior happening again in the future. A reinforcer is some kind of reward, or in the case of adverse outcomes, a punishment.

The Principles of Operant Conditioning

Reinforcement occurs when a response is strengthened. Reinforcers are situation specific. This means that something that might be reinforcing in one scenario might not be in another.

You might be triggered (reinforced) to go for a run when you see your running shoes near the front door. One day your running shoes end up in a different location, so you do not go for a run. Other shoes by the front door do not have the same effect as seeing your running shoes.

There are four types of reinforcement divided into two groups. The first group acts to increase a desired behavior. This is known as positive or negative reinforcement.

The second group acts to decrease an unwanted behavior. This is called positive or negative punishment. It is important to understand that punishment, though it may be useful in the short term, does not stop the unwanted behavior long term or even permanently. Instead, it suppresses the unwanted behavior for an undetermined amount of time. Punishment does not teach a person how to behave appropriately.

Edwin Gutherie (as cited in Schunk, 2016) believed that to change a habit, which is what some negative behaviors become, a new association is needed. He asserted that there are three methods for altering negative behaviors:

- Threshold – Introduce a weak stimulus and then increase it over time.

- Fatigue – Repeat the unwanted response to the stimulus until tired

- Incompatible response – Pair a stimulus to something more desirable.

Another key aspect of operant conditioning is the concept of extinction. When reinforcement does not happen, a behavior declines. If your partner sends you several text messages throughout the day, and you do not respond, eventually they might stop sending you text messages.

Likewise, if your child has a tantrum, and you ignore it, then your child might stop having tantrums. This differs from forgetting. When there are little to no opportunities to respond to stimuli, then conditioning can be forgotten.

Response generalization is an essential element of operant conditioning. It happens when a person can generalize a behavior learned in the presence of a stimulus and then generalize that response to another, similar stimulus. For example, if you know how to drive one type of car, chances are you can drive another similar kind of car, mini-van, SUV, or truck.

Here’s another example offered by PsychCore.

10 Examples of Operant Conditioning

By now, you are probably thinking of your own examples of both classical and operant conditioning. Please feel free to share them in the comments. In case you need a few more, here are 10 to consider.

Imagine you want a child to sit quietly while you transition to a new task. When the child does it, you reinforce this by recognizing the child in some way. Many schools in the United States use tickets as the reinforcer. These tickets are used by the student or the class to get a future reward. Another reinforcer would be to say, “I like how Sarah is sitting quietly. She’s ready to learn.” If you have ever been in a classroom with preschoolers through second-graders, you know this works like a charm. This is positive reinforcement.

An example of negative reinforcement would be the removal of something the students do not want. You see that students are volunteering answers during class. At the end of the lesson, you could say, “Your participation during this lesson was great! No homework!” Homework is typically something students would rather avoid (negative reinforcer). They learn that if they participate during class, then the teacher is less likely to assign homework.

Your child is misbehaving, so you give her extra chores to do (negative punishment – presenting a negative reinforcer).

You use a treat (positive reinforcer) to train your dog to do a trick. You tell your dog to sit. When he does, you give him a treat. Over time, the dog associates the treat with the behavior.

You are a bandleader. When you step in front of your group, they quiet down and put their instruments into the ready position. You are the stimulus eliciting a specific response. The consequence for the group members is approval from you.

Your child is not cleaning his room when told to do so. You decide to take away his favorite device (negative punishment – removal of a positive reinforcer). He begins cleaning. A few days later, you want him to clean his room, but he does not do it until you threaten to take away his device. He does not like your threat, so he cleans his room. This repeats itself over and over. You are tired of having to threaten him to get him to do his chores.

What can you do when punishment is not effective?

In the previous example, you could pair the less appealing activity (cleaning a room) with something more appealing (extra computer/device time). You might say, “For every ten minutes you spend cleaning up your room, you can have five extra minutes on your device.” This is known as the Premack Principle. To use this approach, you need to know what a person values most to least. Then, you use the most valued item to reinforce the completion of the lesser valued tasks. Your child does not value cleaning his room, but he does value device time.

Here are a few more examples using the Premack Principle:

A child who does not want to complete a math assignment but who loves reading could earn extra reading time, a trip to the library to choose a new book, or one-to-one reading time with you after they complete their math assignment.

For every X number of math problems the child completes, he can have X minutes using the iPad at the end of the day.

For every 10 minutes you exercise, you get to watch a favorite show for 10 minutes at the end of the day.

Your child chooses between putting their dirty dishes into the dishwasher, as requested, or cleaning their dishes by hand.

What are your examples of operant conditioning? When have you used the Premack Principle?

Operant Conditioning vs. Classical Conditioning

An easy way to think about classical conditioning is that it is reflexive. It is the behavior an organism automatically does. Pavlov paired a bell with a behavior a dog already does (salivation) when presented with food. After several trials, Pavlov conditioned dogs to salivate when the bell dinged.

Before this, the bell was a neutral stimulus. The dogs did not salivate when they heard it. In case you are unfamiliar with Pavlov’s research, this video explains his famous experiments.

Operant conditioning is all about the consequences of a behavior; a behavior changes in relation to the environment. If the environment dictates that a particular behavior will not be effective, then the organism changes the behavior. The organism does not need to have conscious awareness of this process for behavior change to take place.

As we already learned, reinforcers are critical in operant conditioning. Behaviors that lead to pleasant outcomes (consequences) get repeated, while those leading to adverse outcomes generally do not.

If you want to train your cat to come to you so that you can give it medicine or flea treatment, you can use operant conditioning.

For example, if your cat likes fatty things like oil, and you happen to enjoy eating popcorn, then you can condition your cat to jump onto a counter near the sink where you place a dirty measuring cup.

- Step 1: Pour oil and kernels from a measuring cup into a pot.

- Step 2: Allow the cat to lick the measuring cup.

- Step 3: Place the cup into the sink.

- Step 4: Do these same steps each time you make popcorn.

It will not take long for the cat to associate the sound of the “kernels in the pot” with “measuring cup in the sink,” which leads to their reward (oil.) A cat can even associate the sound of the pot sliding across the stovetop with receiving their reward.

Once this behavior is trained, all you have to do is slide the pot across the stovetop or shake the bag of popcorn kernels. Your cat will jump up onto the counter, searching for their reward, and now you can administer the medicine or flea treatment without a problem.

Operant conditioning is useful in education and work environments, for people wanting to form or change a habit, and to train animals. Any environment where the desire is to modify or shape behavior is a good fit.

Operant Conditioning in Therapy

Stroke patients tend to place more weight on their non-paretic leg, which is typically a learned response. Sometimes, though, this is because the stroke damages one side of their brain.

The resulting damage causes the person to ignore or become “blind” to the paretic side of their body.

Kumar et al. (2019) designed the V2BaT system. It consists of the following:

- VR-based task

- Weight distribution and threshold estimator

- Wii balance board–VR handshake

- Heel lift detection

- Performance evaluation

- Task-switching modules

Using Wii balance boards to measure weight displacement, they conditioned participants to use their paretic leg by offering an in-game reward (stars and encouragement). The balance boards provided readings that told the researchers which leg was used most during weight-shifting activities.

They conducted several normal trials with multiple difficulty levels. Intermediate catch trials allowed them to analyze changes. When the first catch trial was compared to the final catch trial, there was a significant improvement.

Operant and classical conditioning are the basis of behavioral therapy. Each can be used to help people struggling with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

People with OCD experience “recurring thoughts, ideas, or sensations (obsessions) that make them feel driven to do something repetitively” (American Psychiatric Association, n.d.). Both types of conditioning also are used to treat other types of anxiety or phobias.

Applications in Everyday Life

We are an amalgam of our habits. Some are automatic and reflexive, others are more purposeful, but in the end, they are all habits that can be manipulated. For the layperson struggling to change a habit or onboard a new one, operant conditioning can be helpful.

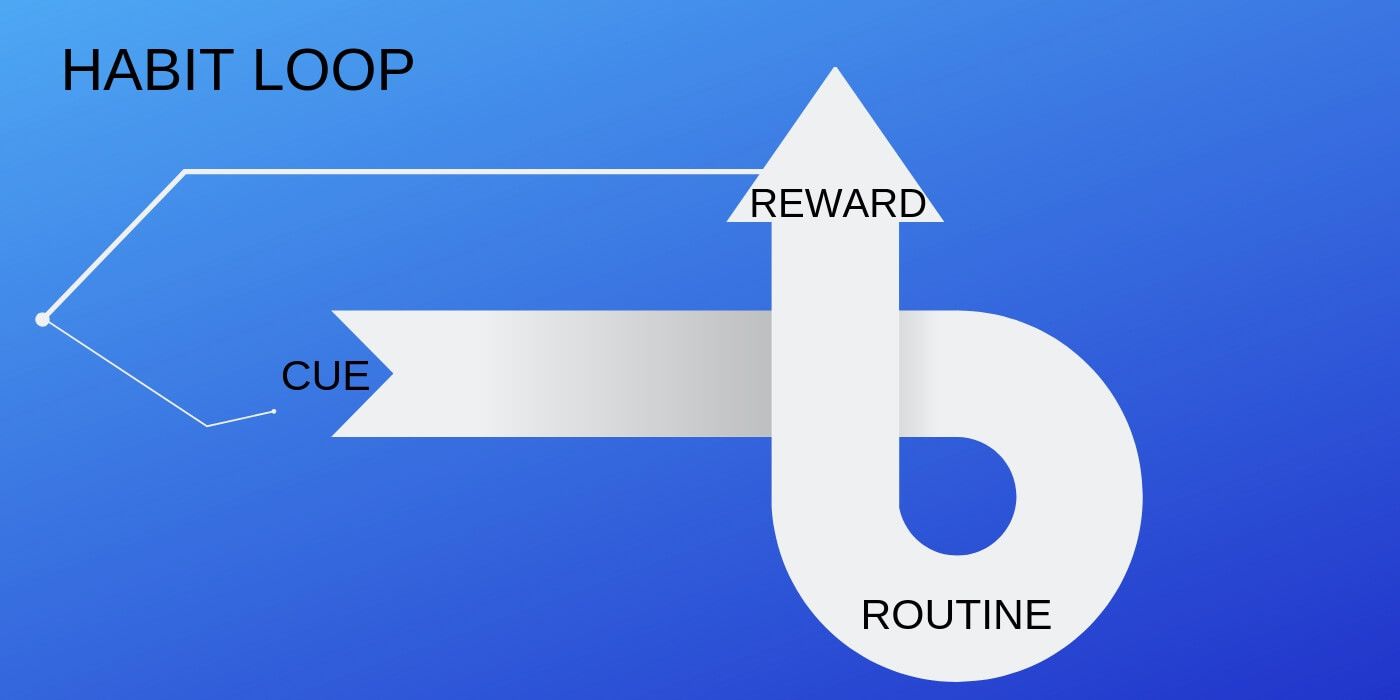

It is the basis for the habit loop made popular in Charles Duhigg’s (2014) book, The Power of Habit.

The cue (trigger, antecedent) leads to a routine (behavior), and then a reward (consequence).

We all know how challenging changing a habit can be. Still, when you understand the basic principles of operant conditioning, it becomes a matter of breaking the habit down into its parts. Our objective is to change the behavior even when the reward from the original behavior is incredibly attractive to us.

For instance, if you want to start an exercise habit, but you have been sedentary for several months, your motivation will only get you so far. This is one reason why this particular habit as a New Year’s resolution often fails. People are excited to get into the gym and shed a few pounds from the holiday season. Then, after about two weeks, their drive to do this is slowly overtaken by a dozen other things they could do with their time.

Using an operant conditioning approach, you can design for your new exercise habit. B. J. Fogg, a Stanford researcher, advocates starting with something so small it would seem ridiculous.

In his book Tiny Habits: The Small Changes that Change Everything, Fogg (2020) guides readers through the steps to making lasting changes. One of the key things to keep in mind is making the habit as easy as possible and more attractive. If it is a habit you want to break, then you make it harder to do and less appealing.

In our example, you might begin by deciding on one type of exercise you want to do. After that, choose the smallest action toward that exercise. If you want to do 100 pushups, you might start with one wall pushup, one pushup on your knees, or one military pushup. Anything that takes less than 30 seconds for you to accomplish would work.

When you finish, give yourself a mental high-five, a checkmark on a wall calendar, or in an app on your phone. The reward can be whatever you choose, but it is a critical piece of habit change.

Often, when you begin small, you will do more, but the important thing is that all you have to do is your minimum. If that is one pushup, great! You did it! If that is putting on your running shoes, awesome! Following this approach helps stop the mental gymnastics and guilt that often accompanies establishing an exercise habit.

This same methodology is useful for many different types of habits.

A word of caution: If you are dealing with addiction, then getting the help of a professional is something to consider. This does not preclude you from using this approach, but it could help you cope with any withdrawal symptoms you might have, depending on your particular addiction.

A Look at Reinforcement Schedules

The timing of a reward is important as is an understanding of how fast or slow the response is and how quickly the reward loses its effectiveness. The former is called the response rate and the latter, the extinction rate.

Ferster and Skinner (as cited in Schunk, 2016) determined that there are five types of reinforcement, and each has a different effect on response time and the rate of extinction. Schunk (2016) provided explanations for several, but the basic schedules of reinforcement are:

- Continuous: Reward after each correct action

- Fixed ratio: Every nth response is rewarded, and the n remains constant.

- Fixed interval: The timing of the reward is fixed. It might occur after every fifth correct response.

- Variable ratio: Every nth response is reinforced, but the value varies around an average number n.

- Variable interval: The time interval varies from instance to instance around some average value.

If you want a behavior to continue for the foreseeable future, then a variable ratio schedule is most effective. The unpredictability maintains interest, and the extinction rate of the reward is the slowest. Examples of this are slot machines and fishing. Not knowing when a reward will happen is usually enough to keep a person working for the reward for an undetermined amount of time.

Continuous reinforcement (rewarding) has the fastest extinction rate. Intuitively this makes sense when the subjects are human. We like novelty and tend to become accustomed to new things quickly. The same reward, given at the same time, for the same thing repeatedly is boring. We also will not work harder, only hard enough to get the reward.

Useful Techniques for Practitioners

Therapists, counselors, and teachers can all use operant conditioning to assist clients and students in managing their behaviors better. Here are a few suggestions:

- Create a contract that establishes the client’s/student’s responsibilities and expected behaviors, and those of the practitioner.

- Focus on reinforcement rather than punishment.

- Gamify the process.

An Interesting Video

PsychCore put together a series of videos about operant conditioning, among other behaviorist topics. Here is one explaining some basics. Even though you have read this entire article, this video will help reinforce what you have learned. Different modalities are important for learning and retention.

If you are interested in learning more about classical conditioning, PsychCore also has a video titled, Respondent Conditioning. In it, the concept of extinction is briefly discussed.

5 Books on the Topic

Several textbooks covering both classical and operant conditioning are available, but if you are looking for practical suggestions and steps, then look no further than these five books.

1. Science and Human Behavior – B. F. Skinner

It is often assigned for coursework in applied behavior analysis, a field driven by behaviorist principles.

Available on Amazon.

2. Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones – James Clear

James Clear started his habit formation journey experimenting with his own habits.

One interesting addition is his revised version of the habit loop to explicitly include “craving.” His version is cue > craving > response > reward. Clear’s advice to start small is similar to both Fogg’s and Maurer’s approach.

Available on Amazon.

3. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business – Charles Duhigg

Duhigg offers several examples of businesses that figured out how to leverage habits for success, and then he shares how the average person can do it too.

Available on Amazon.

4. Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything – B. J. Fogg

The Stanford researcher works with businesses, large and small, as well as individuals.

You will learn about motivation, ability, and prompt (MAP) and how to use MAP to create lasting habits. His step-by-step guide is clear and concise, though it does take some initial planning.

Available on Amazon.

5. One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way – Robert Maurer

He breaks down the basic fears people have and why we procrastinate. Then, he shares seven small steps to set us on our new path to forming good habits that last.

Available on Amazon.

If you know of a great book we should add to this list, leave its name in the comment section.

A Take-Home Message

Operant and classical conditioning are two ways animals and humans learn. If you want to train a simple stimulus/response, then the latter approach is most effective. If you’re going to build, change, or break a habit, then operant conditioning is the way to go.

Operant conditioning is especially useful in education and work environments, but if you understand the basic principles, you can use them to achieve your personal habit goals.

Reinforcements and reinforcement schedules are crucial to using operant conditioning successfully. Positive and negative punishment decreases unwanted behavior, but the effects are not long lasting and can cause harm. Positive and negative reinforcers increase the desired behavior and are usually the best approach.

How are you using operant conditioning to make lasting changes in your life?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- American Psychiatric Association (n.d.). What is obsessive-compulsive disorder? Retrieved January 26, 2020, from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ocd/what-is-obsessive-compulsive-disorder

- Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy and proven way to build good habits and break bad ones. Avery.

- Duhigg, C. (2014). The power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. Random House Trade Paperbacks.

- Fogg, B.J. (2020). Tiny habits: The small changes that change everything. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Kumar, D., Sinha, N., Dutta, A., & Lahiri, U. (2019). Virtual reality-based balance training system augmented with operant conditioning paradigm. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 18, 90.

- Maurer, R. (2014). One small step can change your life: The kaizen way. Workman.

- PsychCore (2018, September 9). We were asked about response generalization effects [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/9U5xylxV0AE

- PsychCore (2016, October 28). Operant conditioning continued [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_JDalbCTpVc

- Schunk, D. (2016). Learning theories: An educational perspective. Pearson.

- Skinner, B.F. (1991). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Copley.

- Skinner, B.F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

- Stangor, C., & Walinga, J. (2014). Introduction to psychology (1st Canadian ed.). BC Campus OpenEd. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Helped me better understand my psychology homework. 🙂

Really love this article as a teacher and as a parent. More enlightened on how to positively influence positive behavior change.

Muito bom o artigo. Parabéns.

Hi, one of your examples “Your child is not cleaning his room when told to do so. You decide to take away his favorite device (positive punishment – removal of a positive reinforcer)…” I believed it should be “negative punishment” instead of positive punishment. Negative punishment means punishment by removal. You are removing what a person wants when he performed an undesired behavior.

Hi Anne,

Great spotting, and thank you for bringing this to our attention! We’ve corrected this in the post now 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager

nice one.