8 Traits of Flow According to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Want to increase your wellbeing, creativity, and productivity?

Want to increase your wellbeing, creativity, and productivity?

If so, you might want to cultivate flow, a concept describing those moments when you’re completely absorbed in a challenging but doable task.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, considered one of the co-founders of positive psychology, was the first to identify and research flow. (If you’re not sure how to pronounce his name, here’s a phonetic guide: “Me high? Cheeks send me high!”)

“The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times . . . The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile”

(Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

The experience of flow is universal and has been reported to occur across all classes, genders, ages, and cultures, and it can be experienced during many types of activities.

If you’ve ever heard someone describe a time when their performance excelled and they were “in the zone,” they were likely describing an experience of flow. Flow occurs when your skill level and the challenge at hand are equal.

Read on to learn more about what flow is and how to cultivate it.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Productivity Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients become more productive and efficient.

This Article Contains:

- Who was Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi?

- The 8 Characteristics of Flow

- Who Experiences Flow?

- What Happens in the Brain During Flow?

- How to Achieve Flow

- Don’t Flow Alone

- What is The Motivation Behind Your Flow State?

- Using Images To Boost Confidence And Flow

- TED Talk On Flow: The Secret To Happiness

- References

Who was Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi?

Csikszentmihalyi became a happiness researcher because of the adversity he faced growing up. He was a prisoner during World War II, and he witnessed the pain and suffering of the people around him during this time. As a result, he developed a curiosity about happiness and contentment.

Csikszentmihalyi observed that many people were unable to live a life of contentment after their jobs, homes, and security were lost during the war. After the war, he took an interest in art, philosophy, and religion as a way to answer the question, What creates a life worth living?

Eventually, he stumbled upon psychology while at a ski resort in Switzerland. He attended a lecture by Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, who spoke of the traumatized psyches of the European people after World War II.

Csikszentmihalyi was so intrigued that he started to read Jung’s work, which in turn led him to the United States to pursue an education in psychology. He wanted to study the causes of happiness.

Finding Out What Happiness Really Is

Csikszentmihalyi’s studies led him to conclude that happiness is an internal state of being, not an external one. His popular 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience is based on the premise that happiness levels can be shifted by introducing flow.

Happiness is not a rigid, unchanging state, Csikszentmihalyi has argued. On the contrary, the manifestation of happiness takes a committed effort.

Beyond each person’s set point of happiness, there is a level of happiness over which each individual has some degree of control. Through research, Csikszentmihalyi began to understand that people were their most creative, productive, and happy when they are in a state of flow.

Csikszentmihalyi interviewed athletes, musicians, and artists because he wanted to know when they experienced optimal performance levels. He was also interested in finding out how they felt during these experiences.

Csikszentmihalyi developed the term “flow state” because many of the people he interviewed described their optimal states of performance as instances when their work simply flowed out of them without much effort.

He aimed to discover what piques creativity, especially in the workplace, and how creativity can lead to productivity. He determined that flow is not only essential to a productive employee, but it is imperative for a contented one as well.

In Csikszentmihalyi’s words, flow is “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it” (1990).

Here’s a short video with a great explanation of flow:

Have you ever experienced flow? There are eight characteristics that this article delves into next.

The 8 Characteristics of Flow

Csikszentmihalyi describes eight characteristics of flow:

- Complete concentration on the task;

- Clarity of goals and reward in mind and immediate feedback;

- Transformation of time (speeding up/slowing down);

- The experience is intrinsically rewarding;

- Effortlessness and ease;

- There is a balance between challenge and skills;

- Actions and awareness are merged, losing self-conscious rumination;

- There is a feeling of control over the task.

Who Experiences Flow?

Interestingly, the capacity to experience flow can differ from person to person. Studies suggest that those with autotelic personalities tend to experience more flow. Such people tend to do things for their own sake rather than chasing some distant external goal. This type of personality is distinguished by certain meta-skills such as high interest in life, persistence, and low self-centeredness.

In a recent study investigating associations between flow and the five personality traits, researchers found a negative correlation between flow and neuroticism and a positive correlation between flow and conscientiousness (Ullén et al., 2012).

It can be speculated that neurotic individuals are more prone to anxiety and self-criticism, which are conditions that can disrupt a flow state. In contrast, conscientious individuals are more likely to spend time mastering challenging tasks–an important piece of the flow experience, especially in the workplace.

What Happens in the Brain During Flow?

The state of flow has rarely been investigated from a neuropsychological perspective, but it’s becoming a focus of some researchers. According to Arne Dietrich, it has been associated with decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex (2003).

The prefrontal cortex is an area of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions such as self-reflective consciousness, memory, temporal integration, and working memory. It’s an area that’s responsible for our conscious and explicit state of mind.

However, in a state of flow, this area is believed to temporarily down-regulate in a process called transient hypofrontality. This temporary inactivation of the prefrontal area may trigger the feelings of distortion of time, loss of self-consciousness, and loss of inner critic.

Moreover, the inhibition of the prefrontal lobe may enable the implicit mind to take over, allowing more brain areas to communicate freely and engage in a creative process (Dietrich, 2004). In other research, it’s been hypothesized that the flow state is related to the brain’s dopamine reward circuitry since curiosity is highly amplified during flow (Gruber, Gelman, & Ranganath, 2014).

How to Achieve Flow

It’s important to note that one can’t experience flow if distractions disrupt the experience (Nakamura et al., 2009). Thus, to experience this state, one has to stay away from the attention-robbers common in a modern fast-paced life. A first step would be to turn off your smartphone when seeking flow.

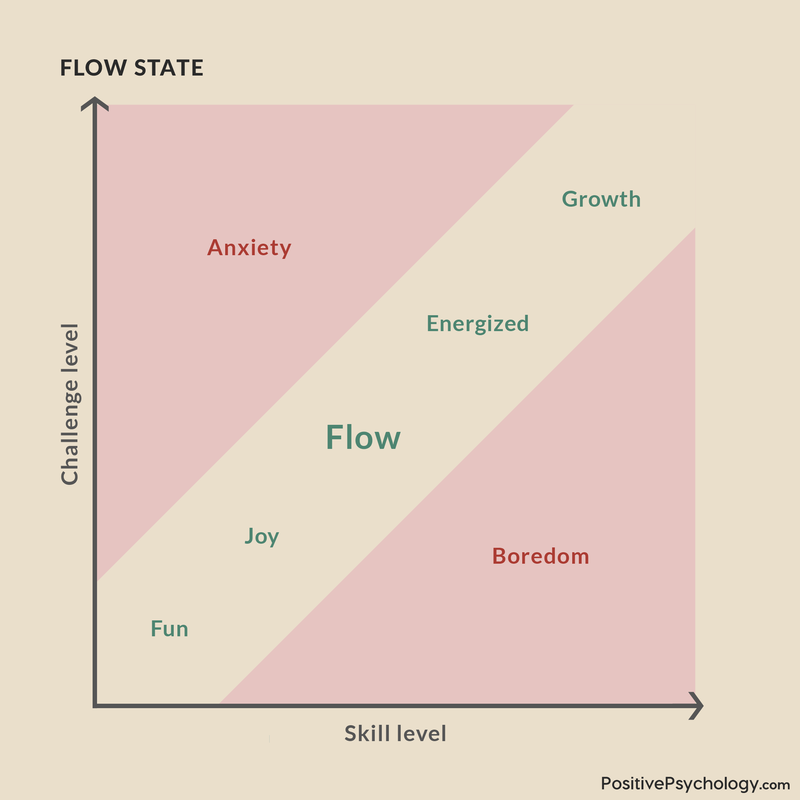

Also, the balance of perceived challenges and skills are important factors in flow (Nakamura et al., 2009). On the one hand, when a challenge is bigger than one’s level of skills, one becomes anxious and stressed. On the other hand, when the level of skill exceeds the size of the challenge, one becomes bored and distracted.

Since the experience of this state is just in the middle, the balance is essential.

“Inducing flow is about the balance between the level of skill and the size of the challenge at hand”

(Nakamura et al., 2009).

The experience of flow in everyday life is an important component of creativity and wellbeing. Indeed, it can be described as a key aspect of eudaimonia, or self-actualization, in an individual. Since it is intrinsically rewarding, the more you practice it, the more you seek to replicate these experiences, which help lead to a fully engaged and happy life.

Don’t Flow Alone

In one study, researchers from St. Bonaventure University asked students to participate in activities that would induce flow either in a team or by themselves (Walker, 2008).

Students rated flow to be more enjoyable when in a team rather than when they were alone. Students also found it more joyful if the team members were able to talk to one another. This finding was replicated even when skill level and challenge were equal (Walker, 2008).

A final study found that being in an interdependent group while experiencing flow is more enjoyable than one that is not (Walker, 2008). So, if you want to get more enjoyment out of flow, try engaging in activities together.

This echoes psychologist Christopher Peterson’s conclusion that positive psychology can be summed up in three words: “Other people matter.”

What is The Motivation Behind Your Flow State?

Most conscious actions require motivation, and there are two basic motivation types: intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic motivation is when you do something because you love it. Csikszentmihalyi said the highest intrinsic motivation is a flow state where self-consciousness is lost, one surrenders completely to the moment, and time means nothing (2013). Think of a competent musician playing without thinking, or a surfer catching a great wave and riding it with joy.

Extrinsic motivation is when your motivation to succeed is controlled externally. That includes doing something to avoid getting into trouble or working hard to earn more money. That type of motivation is short-lived. A good kind of extrinsic motivation is when you are practicing to get better but you still need a tutor or teacher to validate your efforts.

Flow theory interested Jacob Getzels and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi when they studied the creative process during the ’60s (Getzels & Csikszentmihalyi, 1976).

Watching an artist at work, Csikszentmihalyi became intrigued by their single-minded, unique focus and persistence to continue with the painting, despite discomfort, fatigue, or hunger. On finishing the painting, however, the artist ceased showing any interest in the completed work.

Csikszentmihalyi (1975) then took his research into other fields, looking at the circumstances and subjective nature of this enjoyment-related phenomenon in dancers and chess players, to name a few. It was suggested that an optimal flow state was created when people tackled challenges that they perceived to be at just the right level of ‘stretch’ for their skill sets. In other words, neither too tough to elicit anxiety nor too easy to be boring.

As shown in the graph, flow is experienced when one’s skill level and the difficulty of the challenge at hand loosely match. For instance, those with greater skills are likely to experience flow on a task of greater difficulty than those with poorer skills. This “match” is what inspires flow.

Using Images To Boost Confidence And Flow

Psychologists Koehn et al. (2013) conducted research into different performance contexts and the production of the flow state, looking specifically at the way imagery and confidence levels interact to create flow.

Participants completed imagery and confidence measures before undertaking a field test. Measuring the performance of a tennis groundstroke, the researchers found a significant interaction between imagery and confidence (Koehn et al., 2013).

Koehn and colleagues were able to demonstrate positive associations between imagery, confidence and the inducement of a flow state, which in turn predicts increased performance (2013). In essence, the conduction of a flow state is seen to significantly increase performance levels in a given external task (Koehn et al., 2013).

TED Talk On Flow: The Secret To Happiness

We leave you with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s 2004 TED Talk, which has more than 5 million views (and counting).

We’d love to hear from you. How often do you experience flow, and what type of activities lead to this experience?

Drop us a comment below or continue reading about the kind of activities that induce flow here.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Productivity Exercises for free.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). Flow: The psychology of happiness: The classic work on how to achieve happiness. London, UK: Rider.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Flow, the secret to happiness [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/mihaly_csikszentmihalyi_on_flow?language=en

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2013). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Random House.

- Dietrich, A. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: The transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Consciousness and Cognition, 12(2), 231-256.

- Dietrich, A. (2004). Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experience of flow. Consciousness and Cognition, 13(4), 746-761.

- Getzels, J. W., & Cskiszentmilialyi, M. (1976). The creative vision: A longitudinal study of problem finding in art. Wiley.

- Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486-496.

- Koehn, S., Morris, T., & Watt, A. P. (2013). Flow state in self-paced and externally-paced performance contexts: An examination of the flow model. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 14(6), 787-795.

- Lickerman, A. (21 April 2013). How to reset your happiness set point: The surprising truth about what science says makes us happier in the long term. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/happiness-in-world/201304/how-reset-your-happiness-set-point.

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology, 195-206.

- Ullén, F., de Manzano, Ö., Almeida, R., Magnusson, P. K., Pedersen, N. L., Nakamura, J., … & Madison, G. (2012). Proneness for psychological flow in everyday life: Associations with personality and intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 167-172.

- Walker, C. J. (2010) Experiencing flow: Is doing it together better than doing it alone? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 5-11.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Wow. I am an avid equestrian (horse crazy girl grew up, still a horse nut) and now I “understand” what that feeling is called….that perfect “one-ness” and harmony, peace, and “zone” I get when in sync and truly connected, with a horse, mostly happens riding but it could be in training, too. Ive been riding/training most of my 34 years. It is defintley “what I do best” and now it makes sense, why!

Although I will add, I was a hairdresser for 12 years and, when not in a conversation.! (lol) I experienced it cutting hair, as well, for sure. Very cool!!

I also am a creative for sure, and I do get lost painting, but it’s not as “effortless” and quite as euphoric as when Riding. .

Awesome article. Thanks!

Another thing to mention is that psychedelics also down regulate the frontal cortex, just as the flow state does. This hypothesis is probably quite an accurate assessment of what is going on in the mind during the flow state and the psychedelic experience, and the two different experiences really are essentially the same mind state.

I believe that far more research should be done analysing the effect of psychedelic compounds relating to this mind state. The Flow state and the psychedelic experience are so close to each other, and almost feel like being under the influence without having taken a psychedelic. Additionally, from my perspective, taking a psychedelic comes as naturally as breathing, without any of the possible disturbances associated with the experience in “non-flowing” people, such as a bad trip etc. I believe I could do most tasks under the influence of a psychedelic, as easily as when sober (common sense required here obviously, nothing dangerous). I’m not suggesting anybody uninitiated should take a psychedelic expecting to experience flow, as I believe people with this natural mind state are wired differently, and the results will be different for “normal” non flowing people. Under safe supervision however, it may help increase their flow abilities. A “psychedelic school” would be a great thing to see in the future. I know this sounds controversial at the moment, and I understand why as most non flowing people simple don’t experience this mind state on a day to day basis, but trust me when I say to people like me it’s perfectly normal and manageable.

Are introverts excluded from ‘Flow’…?

“Students rated flow more enjoyable when in a team rather than when alone.”

“Students found it more joyful if able to talk to one another. ”

“Being in an interdependent group is more enjoyable than one that is not.”

“If you want to get more enjoyment out of flow, try engaging… together.”

Well yes if you’re an extrovert. In contrast, all of the above are anathema to introverts. I’d suggest that introverts – being creatures of their minds and consciousnesses – are more adept at achieving flow states than anyone.

I read the paper cited (Walker 2010) and, while people might find the activities mentioned fun, I wouldn’t count them as representing flow. One was golf – hardly a good example of not having time to think of anything else. The experimental activities involved hitting a ball, either against a wall, or to each other, which don’t seem to reflect the utilization of skills involved in flow

This is fascinating to me, I now have a better understanding of the state I feel when I create my art. Nothing else matters and it’s bliss.