Goal Setting in Counseling and Therapy (Incl. Examples)

Goal setting is important for those who want to improve their life. Setting goals helps you remain accountable for the things you want to achieve.

Goal setting is important for those who want to improve their life. Setting goals helps you remain accountable for the things you want to achieve.

Goal setting is even more important for those in counseling and therapy. Not knowing how to properly set up goals can often lead to failure.

There are many great techniques when it comes to setting goals, and this article will review many of those.

Setting goals can not only impact mental health, but it can also help you overcome depression and help you with rehabilitation.

Goal setting acts as a roadmap for you to follow when it comes to overcoming challenges and achieving things in life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

- What is Goal Setting in Counseling?

- How Goal Setting Works in Therapy

- How Goal Setting Can Impact Mental Health

- Some Practical Advice for Practitioners

- Applications in Occupational Therapy

- Neuro-linguistic Programming (Goal Setting and NLP)

- Setting Goals with Social Work Clients

- Does Goal Setting Help with Depression?

- A Look at Goal Setting in Rehabilitation

- 4 Goal Setting Counseling Activities

- Using a Goal Setting Workbook

- 5 Goal Setting Workbooks for Counseling

- 6 Goal Setting Worksheet Templates

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Goal Setting in Counseling?

As a counselor, it is your job to set expectations with your clients. There are many different perceptions of what a counselor can do and what someone can expect from the counseling experience.

Counseling theorists don’t always agree on what is an appropriate counseling goal, however, there are some common threads when it comes to standard goals you should be including as part of your practice.

The five most common goals of counseling include:

- Facilitating behavioral change.

- Helping improve the client’s ability to both establish and maintain relationships.

- Helping enhance the client’s effectiveness and their ability to cope.

- Helping promote the decision-making process while facilitating client potential.

- Development.

These goals are guidelines when it comes to helping your clients make positive changes. A big part of the counseling process involves enhancing your client’s ability to cope.

Learned coping skills and patterns are developed throughout our lives, but they may not always work.

Goals are important for everyone, whether they are in therapy or not. Goals help you navigate through life whether they are personal goals, professional goals, a goal to replace a bad habit or simply a goal for achieving success.

Research shows that therapy is much more useful when it involves having a set plan for what you hope to achieve or accomplish. Setting goals can also give the therapist a better grasp of client growth as they proceed with therapy.

According to the Grief Recovery Center, studies show that those who set useful goals during their therapy sessions typically experience less stress and anxiety overall as a result of being able to concentrate better. They often feel happier as well.

Before starting any kind of counseling or treatment plan, it’s also important to set the stage by asking your clients:

- What they want to get out of the counseling or therapeutic process.

- What they believe is inhibiting them from achieving this.

- What their expectations are.

- What their motivations are for making said changes.

Much of this can be done via the interview process where goals can be discussed and prioritized in terms of the desired time frames. Goals are meant to both motivate and challenge the client so it’s critically important that your client be transparent and forthright with what they hope to achieve.

A few things to look out for when creating and setting goals with your client are setting goals unrealistically low, overcoming the fear of failure or continually comparing goals to the goals of others. Helping your clients move out of their comfort zones is an important part of the therapeutic process. As a counselor, your job is to help your clients stretch and grow and move beyond resistance

How Goal Setting Works in Therapy

Setting goals can obviously be very helpful in multiple areas of life. Goals can help you face emotional and behavioral difficulties, reconnect with old friends, help you look for a new job or simply help you save for a vacation.

According to Justin Arocho, Ph.D., there is a general formula that can be followed when it comes to goal setting. The goal setting approach below is used in CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) but it can also be viewed as a standard approach or starting point.

Standard Goal Setting Approach:

- Identify your goal.

- Choose a starting point.

- Identify the steps required to achieve the goal.

- Take that first step and get started.

The first step may sound simple, but it is often challenging. Helping your clients fine-tune and get crystal clear on their goals may be harder than you think. Start by asking them what their overall goal really is.

Identifying a starting point is next. Helping your clients face and understand exactly where they are in terms of this goal is a good place to start. It’s important that they are honest with themselves as well, by examining where things currently stand.

Breaking goals down into small steps is a smart choice for those facing big goals. Breaking goals down into manageable chunks or steps is critical because it helps keep the client from getting overwhelmed.

Remember to keep the steps small and to put them in some kind of logical order. As you discuss this you can also talk about possible obstacles that may arise.

While no one can predict every obstacle that may come about, it will be helpful to discuss strategies for overcoming them.

Taking that first small step is a big achievement for anyone. As a counselor, it is your job to motivate the client to do just that.

How Goal Setting Can Impact Mental Health

According to Rose & Smith, (2018), collaborative goal setting is a robust method when it comes to mental health support. The study, which gathered data over a 14-month time frame found that goal achievement and the strength of a working alliance were demonstrated to have a positive effect on personal recovery, for those in the study.

The GROW Acronym

The GROW acronym is another good model when it comes to tools for recovery.

G – Goal

R – Reality

O – Options

W – Way Forward

G stands for goal.

When it comes to setting goals, it’s important to hone in on what you really want. When setting goals, it’s a good idea to be more specific, rather than general. Being specific will help you fine-tune your goal.

For example, many people try and set goals that are too general such as “I want to get healthy.” A better goal would be something much more specific like “I am going to improve my diet by eating more organic fresh foods and produce and I want to accomplish this by June 1st of this year.”

Asking detailed questions can also help you get more specific about your goal. Questions that are good to ask include:

- Why do you really want this goal?

- How important is it for you to achieve this goal?

- Is this goal realistic?

- How will you know when you have achieved this goal?

- How will you feel after achieving this goal?

- Do you believe you can influence this goal?

- Describe what kind of positive impact achieving this goal will have in your life.

- Describe any downsides when it comes to achieving the goal. If there are any, explain how you can handle that.

R stands for reality.

- As you get further into your goals it’s also imperative to be realistic.

- Try and ask yourself what is happening in terms of your goal at the present moment.

- What kinds of action have you taken in support of this goal?

- What kinds of results have you seen thus far?

- If you are struggling with this goal, you may need to adjust your goal and be more realistic.

O stands for options.

- What options have you explored in terms of achieving this goal?

- What are some other ways you can move forward?

- What else have you learned?

- What are the pros and cons of each of these options?

W stands for a way forward.

- What will you do once you have achieved this goal?

- What kinds of obstacles can you envision you might face?

- How can you plan ahead and come up with some strategies ahead of time?

- You can also rate your success or the possibility of achievement on a 1–10 scale. The number 1 means you have no certainty of achieving this goal and 10 means you have 100% certainty of achieving this goal.

- List three small steps you could take to start bringing yourself closer to this goal within the next 24 hours. This could be something simple like making a phone call, buying a personal journal or purchasing a healthy recipe guide.

Some Practical Advice for Practitioners

Tips to support practitioners in the vital role they play.

How to Avoid Counseling Burnout

Counseling burnout is a real issue, especially for those in the mental health field. Counselors and therapists need to practice good self-care to avoid counseling burnout.

Maintaining that work-life balance is not easy, especially for counselors and therapists. Every day you enter into the personal world of your client, including the anxiety and the stress.

If you are not careful, your client’s pain and suffering will become your pain and suffering.

According to Thomas Skovholt, Ph.D., many counselors find themselves overwhelmed. Being a counselor or therapist requires a huge emotional investment in order to attune yourself to the client.

From mental abuse to addictions to sexual abuse and traumas, it can become overwhelming. According to Skovholt, there is a cycle of caring that is important to understand.

The Cycle of Caring

The “Cycle of Caring,” is a circular process – one in which the ideal treatment process would ideally follow.

- Empathic attachment phase. This first phase is all about developing a personal bond of trust with the client.

- Active involvement phase. The active involvement phase occurs when the counselor dives into the client’s personal issues.

- Felt separation phase. Ideally, this next phase occurs when the therapist ends the counseling relationship. He or she would then ideally reaffirm his or her own identity and separation at that time.

- Re-creation phase. This last phase involves reenergizing. Ideally, the counselor is ready and willing for the next client who comes up.

Signs of Counseling Burnout

- Anxiety

- Apathy

- Compassion fatigue

- Depression

- Feelings of isolation

- Mental exhaustion

- Physical exhaustion

- Difficulty concentrating

- Depersonalization of clients (referring to clients as cases and not people)

Compassion fatigue can occur when you experience an extreme state of tension and preoccupation with the suffering of those being helped. This might occur at such a degree that it could possibly create secondary trauma for the therapist or counselor.

Practicing good self-care can help you avoid compassion fatigue and see things in perspective.

Self-care might include spending more time with friends, curling up with a good goal-setting book or watching a funny movie with your partner or spouse. Any activity that nourishes you is good for self-care.

To avoid counseling burnout, try making a list of 5 things that you can do throughout the week to practice good self-care. You might consider things like:

- Meeting a friend for lunch or coffee.

- Getting a massage.

- Going for a long walk in the park.

- Cooking a lovely meal.

- Taking a night off from technology.

- Making a date with your spouse.

- Taking a warm bubble bath.

- Going to a movie.

- Treating yourself to something nice.

- Taking a day off or planning a vacation.

- Practicing a hobby.

- Taking mini-breaks throughout your day to sit outside.

- Listening to soft music.

- Meditating or deep breathing.

- Connecting with other therapists in the business.

Sometimes you have to make a conscious intention to practice good self-care so you can be a better counselor or therapist.

Applications in Occupational Therapy

Occupational therapists help people do the things they want and need to do through the therapeutic usage of daily activities.

Some common interventions include things like helping children with disabilities participate in school activities or social functions, helping adults or children recover from injuries, or even provide support to older people who may be experiencing cognitive or physical changes.

An occupational therapist typically provides an individual evaluation while working with the client to set and reach goals. An outcome evaluation may also be done so that the therapist can ensure the goals were met or take steps to change the intervention plan.

According to the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, client-centeredness is one of the core values of occupational therapy.

Being able to maintain this client-centeredness within both assessment and treatment plans helps the therapist be an advocate for the client.

Goals for occupational therapy can include:

- Goals for self-care

- Goals for work

- Goals for everyday life or play

An occupational therapist will also work with the client to create a robust plan for achieving goals. Without goals, a client would not have a clear understanding of their desires, needs and wants.

The ultimate goal for occupational therapy is to help someone live a normal and full life as much as possible.

Neuro-linguistic Programming (Goal Setting and NLP)

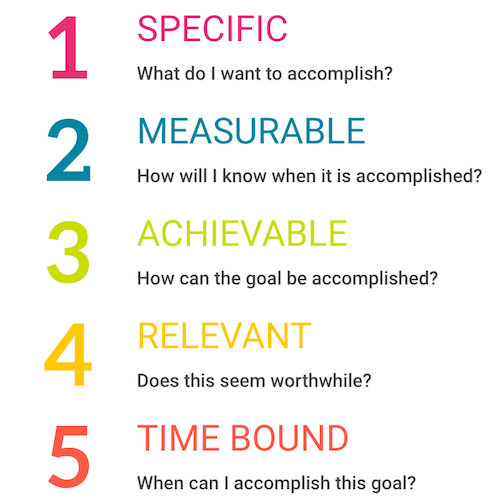

SMART goals are a popular therapeutic technique within NLP and outside of it. A SMART goal is a goal that is:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Realistic

- Time-bound

One of the easiest ways to establish your values and goals is to make them SMART goals. SMART goals help give the client focus and direction while providing a robust plan for change. Setting a SMART goal is a great way to set a goal with a clearly defined focus.

Stating a goal specifically in a few short sentences helps one focus on the end result much better. It’s also important to focus on that end state, or the state of mind one envisions after achieving the goal.

A measurable goal is one that has a very specific target in mind.

For example, you could ask a client how they define success. It’s important to be able to focus on the feeling the lifestyle they want to attain gives them in addition to stating a measurable goal or number. It’s also important to make sure the goal is meaningful for them.

A good financial goal could be something like this:

“I am creating total financial success where I make at least x dollars a month. I am creating the life of my dreams in an easy and relaxed manner.”

An achievable or action-oriented goal should be one that is challenging but realistic. If someone wants a certain level of financial success, it may not be practical or believable to say, I am making 50,000 a month.

A much more practical approach would be to say something like “I am working myself up to making at least $8,000-10,000 a month initially.”

It is better to gradually introduce the mind to a higher and higher goal rather than start out with one that is not believable.

A realistic goal is a goal that has meaning and purpose. Everyone is different so his or her goals will be different. It is important that a client’s goal is fine-tuned to their specific needs.

For goals to be effective they should also have a timetable, otherwise, they may not have relevance. Putting a timetable on a goal, in terms of a specific date in which one is striving to achieve it, can go a long way to motivate someone.

Be sure to give a goal long enough time to realistically achieve it, but not too much time that one loses sight of what they are looking to achieve.

Setting goals helps keep one accountable for their progress along the way. Goals are a great tool for motivation within NLP and outside of NLP.

When you break a goal down to very specific, measurable steps, you will find your goal much easier to follow.

Is your Goal a SMART Goal?

A SMART goal is much more than a simple thought. It is a clearly defined path to success and achievement.

S – Specific

Begin by clearly defining your goal. Make it as specific as possible. Write your goal down and think about ways you can achieve it.

M – Measurable and Meaningful

Make your goals measurable and meaningful. Having a way to measure a goal can make the difference between failure and success.

A – Achievable and Action Oriented

Is your goal achievable and action oriented? Is your goal achievable in the chosen timeframe? What do you need to accomplish to get to your goal?

R – Realistic

Be realistic about how long it will take you to reach your goal. Be clear about the steps necessary to get there.

T – Timely

Goals that are timely are much more likely to be achieved.

Setting Goals with Social Work Clients

A social worker is an academic discipline and a profession that is concerned with individuals, families, groups, and communities. A social worker may be concerned with someone on an individual level or the community as a whole in terms of helping people with tangible services, providing social or health services or even participating in legislative processes.

Goal setting is obviously a big part of a social workers job.

Social workers often serve as liaisons between different institutions and patients. They may also collaborate with other health professionals to ensure a client’s health and wellness.

Working with clients and teaching them how to set goals is an important part of the process.

A social worker might work with a client to help them:

- Explore and assess strengths and challenges.

- Partner together with them to identify short-term and long-term goals.

- Find out what is really important for their growth and life success.

- Develop a plan of action for change.

Does Goal Setting Help with Depression?

Goal setting can also be a useful tool for those suffering from depression. Helping those in therapy set realistic goals has the potential to help people, according to a study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The study found that those who were depressed had more difficulties setting goals and they were also less likely to believe they would achieve those goals.

The study followed 42 individuals with depression. These people were recruited from two clinics in England. The researchers compared the study group with 51 people who did not suffer from depression.

The study did not find that those with depression lacked motivation since the depression group came up with as many goals as the group without depression.

Those with depression did, however, describe more avoidance goals rather than using approach goals. Approach goals might describe positive actions such as expressing more gratitude or taking more walks.

An avoidance goal, on the other hand, strives to reduce negative outcomes such as stopping smoking or reducing anger.

Those in the depression group were more likely to give up on their goals when facing challenges when compared with the control group.

This research provides important clues for helping people with depression set and achieve goals. By helping the depressed client set realistic but achievable goals, you can also help them stay on the right track and persist in the pursuit of that goal.

Treatment planning in counseling – Dr. Todd Grande

A Look at Goal Setting in Rehabilitation

Goal setting is also an important part of the process of rehabilitation in terms of defining outcomes. By coming to an agreement of what is expected, caregivers can then organize their resources as well as their time in support of the rehab process.

This also helps the caregiver determine where to best concentrate resources in terms of expected outcomes.

One of the most important goals in terms of rehabilitation is, of course, the strategic outcome of the rehab process. This outcome will vary widely among clients. For some people, simply returning to a normal lifestyle is the ultimate goal.

Someone else may have a goal to return home with the assistance of a helper or caregiver. Most inpatient rehabilitation programs have very specific goals when it comes to accelerating the return of a patient back to their normal lifestyle.

Setting appropriate goals helps provide the patient with the motivation to succeed.

In a recent study of elderly patients, getting rid of pain, walking, a sense of autonomy as well as returning home were listed as the most frequently reported goals.

The study revealed that shorter lengths of inpatient stays and attainment of goals were significant predictors for improvement when it came to the overall functioning from the patient’s perspective.

4 Goal Setting Counseling Activities

Engaging in activities is a great way to help your client set and achieve goals.

The Average Perfect Day Activity

This activity can help shift your focus from the negative to the positive. Focusing on your perfect day is a great fun activity for anyone.

Start by taking a blank piece of paper or opening a blank document on your computer and writing down your ideal daily schedule.

Consider these things:

- What time do you want to wake up?

- What do you do once you are awake?

- Do you kiss your spouse?

- Do you open up windows and let the sun in?

- Do you go to the kitchen for a cup of coffee or tea?

- What do you do next, take a shower, watch the news, etc.?

- How do you spend your day?

- Who do you interact with?

- What do you do for lunch or dinner?

- How do you relax at the end of the day?

- What would you like to accomplish?

These may seem like simple things but they can create a powerful vision. This perfect day should be a day where you can do whatever you want. This is not about focusing on a major life event, but rather on a typical day.

You can also ask your clients to close their eyes and go through this typical day in their mind.

Emulate Someone You Admire Activity

This activity can help take someone out of their comfort zone by having them imagine themselves as someone they respect or admire.

Start by taking a blank piece of paper or a document on your computer. Write down all of the qualities of this person you admire in each area of life.

- School/Career

- Finance

- Family

- Personal relationships

- Health, etc.

You can also write a brief paragraph on the type of person you strive to be in each of these areas. Try not to limit yourself in any one area like the lack of money or a lack of education for example.

You can also role model someone and take a few moments to close your eyes and see yourself as this happy, successful person.

Develop Goal Setting Plans for Each Area of Life Activity

This is a great activity to revisit someone’s overall goals. Try and encourage your client to create their ideal vision in each area of life.

- Health and wellness.

- Career.

- Social life.

- Personal life.

- Spiritual life.

For example, someone may have a goal to get healthier by cutting back on processed foods and eating more nutrient-dense foods. In terms of family, someone may want to dedicate more time with their children or with their spouse.

Socially speaking, someone may make a goal to get out more with friends and take more time to relax over the weekdays or weekends.

This is a great overall goal-setting exercise that can help someone see the big picture.

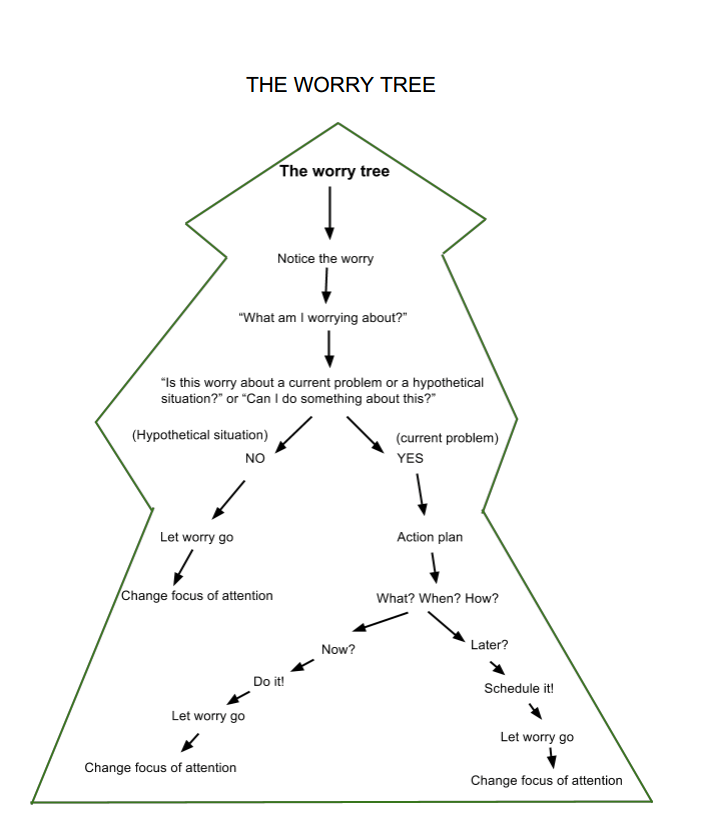

The Worry Tree Activity

The Worry Tree is another simple activity that can really help someone change their focus when they get in a negative spiral.

The Worry Tree helps one break down those negative thoughts.

- When you get a worry, stop and ask yourself what you are really worried about.

- Next, stop and ask yourself what you can do about it, if anything, in the present moment.

- If there is something you CAN do about it, create an action plan. Ask yourself the when, what and how of the situation.

- If you can take action, do so immediately or put it on your agenda for tomorrow, then let the worry go.

- If there is absolutely nothing that you can do about this worry in the present moment, let the worry go! Change your focus of attention.

- Live in the NOW.

- Sometimes just getting your thoughts down on paper can help you see how silly and pointless worrying really is.

Using a Goal Setting Workbook

A goal-setting workbook may very well be the perfect tool for helping someone achieve his or her goals and dreams. Using a workbook allows one to track their progress and get things down on paper.

A workbook also allows one to get clear on their visions, goals, and dreams. All great achievements in life start with an idea. Using a workbook to track those ideas is a smart thing to do.

A goal-setting workbook can help someone:

- Create and track simple goals.

- Create a plan of action for those goals.

- Keep track of what they have accomplished in life.

- Track those things they don’t want to repeat.

- Identify things that are holding them back.

- Identify things that inspire them.

- Identify both short-term and long-term goals.

- Identify areas of life that still need improvement.

- Create new resolutions and goals.

- Create and stick with new habits.

- Create identifiable and quantifiable outcomes.

- See the bigger picture.

- Identify mentors and mastermind groups.

- Break large overwhelming tasks or goals into smaller more manageable goals.

- Hold one accountable for their progress in life.

- Discover their passions and talents.

- Get motivated and excited about life once again.

A goal-setting workbook is a great tracking tool for thoughts and ideas. If someone doesn’t have the motivation to keep a daily journal, a goal-setting workbook is the next best thing because they can check it once a week or so and update their progress.

Read more about goal-setting books here.

5 Goal Setting Workbooks for Counseling

We share a list of workbooks that can aid counselors with goal setting for their clients.

1. Live Your Legend goal setting workbook

This workbook helps you understand your strongest beliefs and what kind of changes you may need to embody them.

2. Zig Zigler goal setting process workbook

This workbook, written by Richard Spackman, reviews 8 action steps to achieving goals. The book is designed to tie together Zig Zigler’s goal setting system.

3. Creative goal setting workbook by Marianne Thorne

Marianne Thorne is an attitude coach. Her workbook reviews 12 areas of creative goal setting: consciousness, contribution, family, health, home, leisure, material things, personal development, relationships, resources, self, and the planet.

4. Ten Steps to Success: Write it Down and Make it Happen by Matt Morris

Matt Morris is a best-selling author, speaker, and life coach. This workbook outlines a 10-step formula for successfully setting up and achieving your goals. The book also reviews ways to stay motivated, how to apply SMART goals and how to develop a mindset of excellence.

5. Goal Setting: Goals & Motivation

Goal Setting: Goals & Motivation: An Introduction to a Complete & Proven Step-by-Step Blueprint for Reaching Your Goals by Martin Kaye.

Martin Kaye is the founder of the Better Self Academy. This book offers an evidence-based introduction into the world of goal setting. The book promotes the importance of using your strengths, how to avoid the rat race and how motivation really works.

By offering simple daily routines, this book provides a nice overview for setting and achieving goals.

6 Goal Setting Worksheet Templates

Many people fail when it comes to setting goals because they don’t have a plan. Having ideas is great, however, if you fail to write them down or fail to act upon them, they probably won’t happen.

Helping your clients set and achieve goals is a large part of the therapeutic process. Having a good supply of templates to access can help you do just that.

One great template to use is the SMART Goal Setting Worksheet. This worksheet can go a long way to helping your clients hone in on their dreams and goals.

This template can help your client not only identify their goal but help them get really clear on why the goal is important.

With this worksheet, you can also identify potential problems, and create action items to help the goal become a reality.

The Goal Execution Worksheet is another great option. In this worksheet, you will find a place to record goals and action steps, start dates as well as starting metrics and final metrics.

The Simple Goal Setting Worksheet is another option. Sometimes simpler is better, especially if clients are feeling overwhelmed.

The Simple Goal Setting Worksheet has a place to record goals, a place for the anticipated completion date, as well as two things that can help someone reach the goal. This worksheet is also a smart choice for those who might be having difficulties creating and achieving goals.

The Goal Exploration Worksheet is designed to help your clients examine goals across several different areas of life, including social, career, physical, family, leisure and even personality. Creating meaningful goals across multiple areas of life can be very beneficial for those who are struggling.

The Goal Planning Worksheet is another handy tool. This worksheet can help your client set clear goals as well as envision obstacles and strategies for reaching those goals. This worksheet can help your clients set goals for the short-term as well as the long-term.

The Therapy Goal Worksheet is designed to help develop treatment goals at the onset of therapy. It can also be used to set a direction in therapy as well as help create desired outcomes.

This worksheet also contains the Magic Wand question, which is a great tool to help develop the imagination. This worksheet is a valuable tool for treatment planning and creating an outline for future therapy sessions.

Worksheets can be a great tool for people who have trouble envisioning their goals clearly.

A Take-Home Message

Goal setting is certainly an important part of the counseling process. Setting goals can help someone bridge the gap between what they imagine in their mind to making it happen in the real world.

Helping your clients set strong empowering goals can help hold them accountable in the long run. While it seems relatively simple to sit down and write out a goal, it’s not always easy to find the motivation to create a robust goal.

That is where the therapist or counselor comes into play. Teaching your clients to own their own success by setting powerful goals can go a long way in the recovery process.

As a counselor, you have an important job. However, it’s also important to practice good self-care so you can avoid counseling burnout. If you are not at your absolute best, the client will sense it and not benefit as much from the counseling process.

In the end, the counseling relationship is a collaborative one. Helping your clients understand that therapy is only as good as the information you get can help them learn to be more open and honest during the counseling process.

The therapeutic process can be quite an amazing process and a tool that is transformative for everyone.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- Arocho, J. (2019, March 18). How CBT uses goal setting. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from http://www.manhattancbt.com/archives/544/cbt-uses-goal-setting/

- Beyond Goal Setting to Flourishing. (2017, September 27). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/highlights/spotlight/issue-101

- Dickson, J. M., Moberly, N. J., O’Dea, C., & Field, M. (2016). Goal fluency, pessimism and disengagement in depression. PLOS ONE, 11(11).

- Foundations Counseling, LLC. (2017, October 09). The Importance of Goals and Goal Setting. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.foundationscounselingllc.com/blog/importance-of-goals-and-goal-setting.php

- Goals Worksheets. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.therapistaid.com/therapy-worksheets/goals/none

- Hamilton-Kuby, C. (2017, January 3). SMART and WISE Gaol-Setting Using Neuro-Linguistic Programming. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://coachfederation.org/blog/smart-wise-goal-setting-using-neuro-linguistics-programming-nlp

- Lipovsky, W. (2018, September 25). Occupational Therapy Goals: Short-Term, Long-Term Examples. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://firstquarterfinance.com/occupational-therapy-goals-examples/

- Nikitina, A. (2018, January 03). One of the Best Goal Setting Exercises. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.lifehack.org/articles/productivity/one-the-best-goal-setting-exercises.html

- Nowack, K. (2017). Facilitating successful behavior change: Beyond goal setting to goal flourishing. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(3), 153–171.

- Rethink Mental Illness. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.rethink.org/living-with-mental-illness/recovery/tools-for-recovery/goal-setting

- Rose, G., & Smith, L. (2018). Mental health recovery, goal setting and working alliance in an Australian community-managed organisation. Health Psychology Open.

- Self-care Tips for Therapists and Counselors. (2017, December 08). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.theranest.com/blog/self-care-tips-for-therapists/

- The Importance of Goal Setting in Therapy. (2019, February 21). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.griefrecoveryhouston.com/importance-of-goal-setting-in-therapy/

- Thomas, B. (2018, June 25). What Are the Goals of Counseling?

- Understanding the Role of a Social Worker. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://mswonlineprograms.org/job-duties-and-responsibilities-of-social-workers/ation.com/social-sciences/What-are-the-goals-of-counseling

- Villines, Z. (2017, January 04). Effective Goal Setting Could Help People with Depression. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/effective-goal-setting-could-help-people-with-depression-0105171

- Writers, S. (2018, October 01). Avoiding Counselor Burnout While Seeking Resilience. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://counselor-license.com/articles/avoiding-burnout-skovholt/

- www.getselfhelp.co.uk/docs/worrytree.pdf

- https://liveyourlegend.net/

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

It is very useful