Exploring the Body Mind Connection (Incl. 5 Techniques)

Even before Sigmund Freud and the psychoanalysis movement, psychologists have argued why the body-mind concept is crucial to psychology.

Even before Sigmund Freud and the psychoanalysis movement, psychologists have argued why the body-mind concept is crucial to psychology.

The reasoning for this stems from the idea that physical conditions affect mental health, and that mental conditions affect physical health.

Unlike desires or dreams, our thoughts and emotions don’t only exist in the mind. Feelings are, well, actual and physical feelings.

People get “butterflies in the stomach” onstage or on a first date, while others who anger easily are described as “hot-headed.”

The body holds your physical health and your ability to function. For example, even the little actions like walking and the fine movements of your fingers depend on a healthy body.

But the mind houses your spirit and your motivation to function. These days, we have evidence that mental and physical health are so related to each other, that studies about mind-body integration in psychology seem especially important (Taylor, Goehler, Galper, Innes, Bourguignon, 2010).

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- Defining Body-Mind Integration

- Mapping Our Emotions: Researching The Physical Presence of Emotions

- The Physical Impact of Positive and Negative Emotions

- How Can We Explain This Mind-Body Integration?

- The In’s and Out’s of Body Intelligence

- Body-Mind Integration Techniques

- Positive Psychology and Body-Mind Integration

- Going Forward

- A Take-Home Message

- References

Defining Body-Mind Integration

There are different approaches to understanding mind-body integration. Some researchers argue that body-mind integration is crucial in the medical field, since patients don’t feel an obvious division between their bodies and their minds. Thus, physicians shouldn’t make diagnoses that separate the mind from the body (Davidsen et al., 2016).

A medical approach to mind-body integration is most concerned with treating patients shallowly, and to avoid treating symptoms without considering holistic solutions.

To summarize what Selhub (2007) stated:

“In mind-body medicine, the mind and body are not seen as separately functioning entities, but as one functioning unit. The mind and emotions are viewed as influencing the body, as the body, in turn, influences the mind and emotions”

(p. 4).

Aside from the strictly medical approaches, there are also neurologically-based models of mind-body integration. For example, Taylor et al. (2010) discuss a number of psychophysiological-based models where certain neurons and muscles affect mental states such as stress.

The models of various studies all indicate a bidirectional effect driven by both top-down and bottom-up factors.

In this case, top-down mechanisms are defined as those which initiate in mental processes in the cerebral cortex, and bottom-up mechanisms are those which begin with sensory receptors.

Let’s see an example in practice.

Mapping Our Emotions: Researching The Physical Presence of Emotions

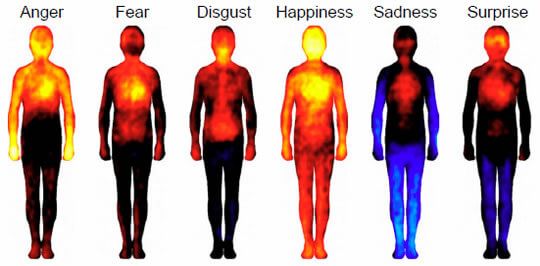

One 2013 study focused on where people experience different emotions in the body. This research constituted the first “map” that illustrated the links between our emotions and our body sensations.

In the study, a team of Finnish researchers induced different emotions in 701 participants and then asked them to color in a body map of where they felt increasing or decreasing activity (Nummenmaa, Glerean, Hari, & Hietanen, 2014).

Participants in the study were from both Western European countries (Finland and Sweden) and well as East Asian countries (Taiwan). Despite the cultural differences, the researchers found remarkable similarities in how participants responded.

The researchers explain their findings:

“Most basic emotions were associated with sensations of elevated activity in the upper chest area, likely corresponding to changes in breathing and heart rate. Similarly, sensations in the head area were shared across all emotions, reflecting probably both physiological changes in the facial area […] as well as the felt changes in the contents of mind triggered by the emotional events.”

The pictures below represent the body maps for the six basic emotions. Yellow indicates the highest level of activity, followed by red. Black is neutral, while blue and light blue indicate lowered and very low activity, respectively.

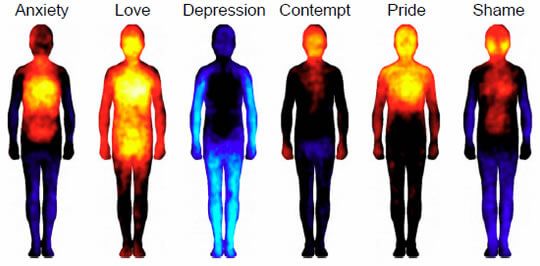

Along with the basic emotions, here are the body maps of six more complex emotions:

You can find the original blog post here. It’s now time that we explore why we feel sensation with these corresponding emotions.

The Physical Impact of Positive and Negative Emotions

Each emotion we experience has a different representation in the body. Let’s unpack these main emotions and their physical responses:

1. Happiness

Happiness is the one emotion that fills the whole body with activity. This might indicate a sense of physical readiness that comes with a happy state, and heightened communication between the body and the brain. We usually feel secure when we are happy, so in this state, we can devote all of our attention to experiencing ourselves as a part of a pleasure-rich world around us.

2. Love

This is another standout emotion that fills the body with activation, stopping just short of the legs. Love is often intertwined with physical desire, so it unsurprisingly activates sensation in the reproductive organs more strongly than happiness does.

The emotional focus of love is both the object of affection and the intensity of emotions in the subjective self; thus, activation is intense around the head and chest but more difficult to notice in the lower extremities.

3. Pride

This emotion floods the head and chest areas with a very intense sensation. This pattern of activation corresponds to a focus on the self, with resources and awareness drawn inwards and away from the extremities.

Although surprise follows a similar pattern, the strength of the activation is much less pronounced, as resources draw inwards to prepare the body to face danger. Because surprise can be positive, negative, or neutral, the body experiences it in a way that reflects uncertainty about the triggering event.

4. Anger

Anger stands alone as the negative emotion with the most intense activation, particularly in the head, chest, and hands. The angry body prepares itself for conflict by focusing attention and resources on the parts of the body that might have to act.

When we picture anger or a time when we felt enraged, many people describe an overwhelming desire to hit something. This aligns with the image scan where sensation floods to our hands.

5. Fear

Fear holds a similar but much more understated pattern of activation, as the body prepares to either fight-or-flight, but isn’t necessarily seeking outright conflict.

Evolutionarily, fear required immediate thought: do I decide to run away from this predator, or fight to the death? In modern terms, do I feel that I can stand my ground with this frightening dog, or should I flee? Thus, it makes sense that we experience fear with a rush of sensation to the head.

6. Disgust

Disgust pulls the resources of the body even more tightly into the core of the body. This emotion causes the body to prepare to expel any noxious substances it has ingested, hence the focus of activation along the digestive tract.

When we experience disgust towards other humans, perhaps we feel a concentration of sensation in our vital organs, as a natural protective response to repulsion.

7. Shame and Contempt

Although shame and contempt have similar patterns of activation, contempt stimulates less activation in the chest. This may be because the focus of contempt is outside of the self and the judgment of others. Shame, on the other hand, focuses on a sense of personal failure and judgment of yourself for causing this to happen.

The depression of activity in the extremities is very pronounced in shame. Perhaps this is because the body withdraws resources into itself in a fight-or-flight response.

8. Anxiety

Anxiety is a form of long-term, low-grade stress. It activates the chest intensely and can lead to a sense of doom or dread, as experienced by panic attacks. People who experience panic attacks frequently report tightness and pain in the chest, and an inability to think beyond the pressing fear of the moment.

These feelings might correspond to the strain the heart and lungs feel as they struggle to deliver oxygen to a body under conditions of extended fear.

9. Depression

This has the most noticeable map of our negative emotions. It stimulates no activation in any part of the body and lowers activation in the extremities.

In a state of depression, it is difficult to connect with the active self and the outside world. Sadness does not suppress feeling in the head and chest and often contributes to a general lack of agency or activity.

How Can We Explain This Mind-Body Integration?

Because emotions manifest in the body as physical sensations, it follows that physical sensations can produce corresponding emotions. Molecular neuroscientist Lauri Nummenmaa explains this below:

“Emotions adjust not only our mental, but also our bodily states. This way they prepare us to react swiftly to the dangers, but also to the opportunities […] Awareness of the corresponding bodily changes may subsequently trigger the conscious emotional sensations, such as the feeling of happiness.”

For example, it is likely that the warmth of a blanket wrapped around your shoulders on a cold day, translates from a physical sensation of heat to an emotional feeling of happiness and security.

The connection between our minds and our bodies is something we instinctively feel, but how much attention do we pay to your bodily sensations each moment?

To understand our own emotional lives and those of the people around us, we need a deeper awareness, achieved through the practice of mindfulness and the development of body intelligence.

Take a moment to acknowledge how you physically feel right now, as well as your next emotional flood of joy, sorrow, and calm. Over time, this can help you feel more in touch with these aspects of existing, and providing you with a rich understanding of your whole mind and body connection.

Body intelligence is a psychological method that highlights the importance of recognizing body sensations as a way to improve our health.

The first step is to recognize the internal cues and sensations that your body tells you.

The In’s and Out’s of Body Intelligence

The body is the subject of constant stressors, both external and internal (Antonovsky, 1993).

As an integral part of the human machine, it communicates what it needs in order to survive and cope with stressors—we just need to actively listen.

When we are confronted with difficult emotions, maladaptive ways like self-medicating or practicing denial, are frequent ways people cope with undesirable feelings. What if, instead, we leaned into these unpleasant feelings as messages from our bodies to our brains?

Although relieving at the moment, a maladaptive coping mechanism can be detrimental to health. They don’t facilitate the long-term improvements we need to address the actual source of discomfort. Body intelligence offers tools to strengthen the mind-body link and work towards positive wellbeing.

Body intelligence cannot remove illness, but it can attune you to what your body is feeling. It can alleviate certain symptoms of stress such as chest pain, headaches, heart rate variability, and others.

What to know more about the details of body intelligence? Take a listen to this podcast from Live Happy. It explains the details and benefits of listening to the physical sensations of our body.

The clip below provides an example of the tools that can help us become attuned with our body, and how to relieve stress in holistic ways.

Duperly et al. (2008) found that, for medical students, maintaining a positive attitude was crucial in their preventative health measures.

Students with a positive attitude accepted preventive counseling better before stress or disorders became all-consuming. This example of disease prevention is a key example of how attitude shapes other aspects of life and impacts health.

So how do we influence this unconscious dynamic between our thoughts, emotions and physical sensations?

Below is a comprehensive list of techniques that help to build body intelligence, tune our attention, and increase body awareness for greater physical and mental health.

Body-Mind Integration Techniques

The body-mind integration field includes a number of disciplines and approaches. Here is the main goal of this technique:

“The goal of mind-body techniques is to regulate the stress response system so that balance and equilibrium can be maintained and sustained, to restore prefrontal cortex activity, to decrease amygdala activity, and to restore the normal activity of the HPA axis and locus ceruleus-sympathetic nervous system”

(Selhub, 2007, p. 5).

The medical field includes a wide range of “alternative” techniques aiming to increase awareness and strengthen the mind-body link.

Five examples of these modalities include mindfulness, meditation, relaxation, biofeedback, and the three practices of Yoga, T’ai Chi, and Qigong (McGuire, Gabison, & Kligler, 2016). Let’s explore these more deeply.

Mindfulness

“Mindfulness is characterised by dispassionate, non-evaluative and sustained moment-to-moment awareness of perceptible mental states and processes. This includes continuous, immediate awareness of physical sensations, perceptions, affective states, thoughts, and imagery”

(Grossman, et al., 2003).

Mindfulness is a powerful tool in the treatment of mental health disorders, stress-related conditions, cancer, and cardiovascular conditions.

People who are prone to depression, anxiety and stress-related conditions, often engage in overthinking and rumination. They also struggle with disconnecting from their thoughts and worries, which can drive someone into exhaustion.

Mindfulness is vital for people struggling, as a way to direct attention on the present experience.

Fazekas, Leitner, and Pieringer (2010) cite the importance of accurate detection of emotions as a way to practice effective self-regulation.

Internal cues are a very available way to develop body intelligence; for example, recognizing “I feel anxious today in my body,” actually causes the amygdala to relax. The body calms down when the mind recognizes what it is feeling (2010).

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction is another example of mindfulness-based therapies. It is a structured course which offers its participants a new lease on life, health, and wellbeing. Essentially, mindfulness redirects attention to the external environment so we can escape the unwinding of our neural and negative thought loops, or pain and discomfort.

By disrupting past patterns of thought, these approaches slow the heart rate and calm the breath, which continues to relax the body and then flood the body with more pleasant neurotransmitters. This, in turn, creates a positive feedback loop.

This TEDtalk by translational neuroscientist Catherine Kerr is a great introduction to mindfulness. She explains how focusing on our toes can help reduce negative thoughts.

As Kerr explains, mindfulness starts with the body and noticing the details of what sensations we feel, say, starting with our toes. Our sensory attentional system is one gateway to a richer mind-body connection—and the health of an attuned human.

2. Meditation

In traditional meditation, the main focal point for attention training is on the inhalation and exhalation of air through the nose. Research into the breath confirms that by being attuned to your breathing, and paying attention to it, naturally slows your breathing.

This helps the body relax, resulting in less anxious, depressed and angry.

Below is one example of the meditation resources available. It is a traditional meditation practice which focuses on training the attention on the breath. Even 3-minutes of meditation can ease a stressed brain.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed with all the resources available, consider trying one, every day, for a 5-minute session. Maybe before eating dinner, or upon waking up, there is time for you to reset your brain.

3. Relaxation techniques

There are times to be alert and stressed. A lot of the time, however, we do not need the hyper-alert sensation of stress. How do we help ourselves relax? There are many ways.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) is one example of relaxation therapy which is known to build body intelligence. PMR teaches us to systematically tense and then release muscles, working on one muscle group at a time. This process results in reduced physical stress and tension by increasing our focus on the body.

There are other relaxation techniques including the Body Scan and other forms of self-care.

4. Biofeedback

A pioneering technique for building body intelligence is biofeedback. This is the use of scientific and physiological monitoring of the body to effectuate awareness of body states with electrodes. EMG, or Electromyography, enables people to make changes to the state of their body (Ancoli, Peper, & Quinn, 2011).

The evidence supporting biofeedback has been strong; it can reduce certain disorders such as high blood pressure and migraines. One of the most significant perks of biofeedback is the self-direction that it elicits.

If you are interested in learning more about biofeedback and how it can provide effective treatment for different illnesses, then watch this full-length lecture from the University of California, San Fransisco, Osher Centre for Integrative Medicine:

Headaches, asthma, recurrent abdominal pain, pelvic pain, and sleep disorders are just some of the ailments that biofeedback can help with.

5. Yoga, T’ai Chi, Qigong

These three physical practices focus on using body movements that draw attention to the internal experience of the present.

The slow and steady pace of the movements helps relax us and reduce physical stress. They also create a focused state of mind which helps with negative emotions. A report from Harvard Health explored the benefits of these three body-mind-integration techniques, exploring how it aids with anxiety and depression.

Positive Psychology and Body-Mind Integration

In two recent studies, mind-body techniques helped with depression in children and adults.

A study by Staples, Atti, and Gordon (2011) highlighted significant improvements in depressive symptoms and a lowered sense of hopelessness for 129 Palestinian children and adolescents in a 10-session mind-body skills group.

These mind-body skills included meditation, guided imagery, breathing techniques, autogenic training, biofeedback, genograms, and self-expression through drawings and movement.

After 7 months, the improvements still helped with ongoing hardships and conflicts. Even the doomed sense of hopelessness was lifted.

There are several positive psychology interventions using mind-body integration (Wong et al., 2015; Zeller et al., 2004). For example, Jindani and Khalsa (2015) investigated the effects of a yoga program on participants with post-traumatic stress disorder. Participants found the yoga intervention to be “highly effective.”

PTSD itself can also be regarded as a mind-body disorder, as symptoms can manifest in both the physical and mental bodies. A mind-body treatment plan seems necessary for this condition.

A review of “alternative medicines” (such as yoga, hypnosis, and meditation) found that they can be helpful in managing stress and affecting other mental conditions (Park, 2013). Park claims that these findings support why body-mind treatments should be integrated into clinical psychology.

With all the evidence showing the impact of mind-body treatments in treating mental disorders, improving mental health, and fostering better physical health, why are these practices not common practice in clinical psychology yet?

Positive psychologists are ready for this holistic approach to wellbeing to become mainstream.

Going Forward

Body-mind integration is largely an untapped resource in the field of psychology. There are several different theories on mind-body integration as it relates to medical and psychological issues, and with more research, it may only be a matter of time before most psychologists incorporate these techniques.

If the mind and body are truly integrated, rather than one side simply responding to the other, then a deeper body-mind connection is key for overall physical and mental health.

One next step to strengthen these studies is to measure wellbeing by explicitly measuring physical wellbeing as well as mental wellbeing. Positive psychology teachings could also seek to teach people a more holistic understanding of self.

A greater sense of body intelligence, when learning to deal with life’s challenges, relates to other goals in the field of positive psychology. For example, teaching resilience to clients, or practicing self-care for ourselves, align with these goals to care for our bodies and mind.

A Take-Home Message

The mind and the body are the greatest tools we possess to achieve positive wellbeing. It is imperative that we learn body intelligence, and use it as part of the treatment and prevention of physical and mental illness.

Practices such as progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, meditation, mindfulness, biofeedback, and yoga, are just a few ways to strengthen body-mind connections.

Positive psychology interventions have included mind-body integration techniques so far. Anyone who seeks to improve their physical or mental health can gain from this holistic approach of body-mind integration.

Which of the five practices might you incorporate into your routine, and how? Are there other resources you use that help you or your clients with mind-body wholeness?

We would love to hear from you in our comments section below.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Ancoli, S., Peper, E., Quinn, M. (2011). Mind/body integration: Essential readings in biofeedback. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). Complexity, conflict, chaos, coherence, coercion and civility. Social Science & Medicine, 37(8), 969-974.

- Duperly, J., Lobelo, F., Segura, C., Sarmiento, F., Herrera, D., Sarmiento, O. L., & Frank, E. (2009). The association between Colombian medical students’ healthy personal habits and a positive attitude toward preventive counseling: Cross-sectional analyses. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 1-7.

- Fazekas, C., Leitner, A., & Pieringer, W. (2010). Health, self-regulation of bodily signals and intelligence: Review and hypothesis. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift, 122(23), 660-665.

- Jindani, F. A., & Khalsa, G. F. S. (2015). A yoga intervention program for patients suffering from symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(7), 401-408.

- McGuire, C., Gabison, J., & Kligler, B. (2016). Facilitators and barriers to the integration of mind-body medicine into primary care. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 22(6), 437-442.

- Nummenmaa, L., Glerean, E., Hari, R., & Hietanen, J. K. (2014). Bodily maps of emotions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(2), 646-651.

- Park, C. (2013). Mind‐body CAM interventions: Current status and considerations for integration into clinical health psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 45-63.

- Selhub, E. (2007). Mind-body medicine for treating depression: Using the mind to alter the body’s response to stress. Alternative & Complementary Therapies, 13(1), 4-9.

- Staples, J., Atti, J., & Gordon, J. (2011). Mind-body skills groups for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in Palestinian children and adolescents in Gaza. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(2), 246-262.

- Taylor, A. G., Goehler, L. E., Galper, D. I., Innes, K. E., & Bourguignon, C. (2010). Top-down and bottom-up mechanisms in mind-body medicine: Development of an integrative framework for psychophysiological research. Explore, 6(1), 29-41.

- Wong, W. W., Ortiz, C. L., Stuff, J. E., Mikhail, C., Lathan, D., Moore, L. A., … & Smith, E. O. B. (2016). A community-based healthy living promotion program improved self-esteem among minority children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 63(1), 106-112.

- Zeller, M., Kirk, S., Claytor, R., Khoury, P., Grieme, J., Santangelo, M., & Daniels, S. (2004). Predictors of attrition from a pediatric weight management program. The Journal of Pediatrics, 144(4), 466-470.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Really enjoyed the information!