We recently posted an article about how to incorporate a regular practice of gratitude into your life.

We recently posted an article about how to incorporate a regular practice of gratitude into your life.

It includes some excellent tips, ideas, and exercises to start being more grateful.

However, most people like to know how they can benefit before they start a regular practice. That’s an understandable desire, of course. I would never start eating boring but healthy food on a daily basis without hearing about the fantastic benefits it could bring to my life!

In the interest of informing our readers about how they can benefit from practicing gratitude, and perhaps encouraging some of you who are on the fence, we put together findings from multiple studies and articles into one resource that you can use to decide whether practicing gratitude is a good decision for you.

Once you’ve seen all of these wonderful potential benefits, I think I know what your decision will be!

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Gratitude Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients connect to more positive emotions and enjoy the benefits of gratitude.

This Article Contains:

The 28 Benefits of Gratitude

This piece from Happier Human is a good starting place when exploring the benefits of gratitude (Amin, 2014).

The benefits are split into five groups:

- Emotional benefits

- Social benefits

- Personality benefits

- Career benefits

- Health benefits

There are many benefits of gratitude, but these categories cover quite a few of them.

Gratitude and Emotional Benefits

1. Make us happier

Simply journaling for five minutes a day about what we are grateful for can enhance our long-term happiness by over 10% (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005)! It turns out that noticing what we already have can make us feel more positive about our lives, which makes a simple sort of sense:

those who pay attention to what is good in their life instead of what is bad are more likely to feel positively about their life.

2. Increase psychological wellbeing

Researcher Chih-Che Lin (2017) found that even when controlling for personality, a high level of gratitude has a strong positive impact on psychological wellbeing, self-esteem, and depression. Basically, this means that we can reap the best benefits of gratitude by embodying gratitude and truly living a life of gratitude, a state that we can get to through regular practice and commitment.

3. Enhance our positive emotions

Feeling grateful every day keeps the envy at bay! Research has shown that gratitude reduces envy, facilitates positive emotions, and makes us more resilient (Amin, 2014). After all, if we are grateful for what we have, what room is there for envy to sneak in?

4. Increase our self-esteem

Participants who completed a four-week gratitude contemplation program reported greater life satisfaction and self-esteem than control group participants (Rash, Matsuba, & Prkachin, 2011). Gratitude can help you feel better about your circumstances, which can lead to feeling better about yourself.

5. Keep suicidal thoughts and attempts at bay

A study on the effects of gratitude on depression, coping, and suicide showed that gratitude is a protective factor when it comes to suicidal ideation in stressed and depressed individuals (Krysinska, Lester, Lyke, & Corveleyn, 2015). Enhancing our own practice of gratitude can help protect us when we are weakest.

Gratitude and Social Benefits

It makes sense, then, that all of these positive effects result in social benefits as well. After all, happy and healthy people are fun to be around!

Regarding social benefits, regularly practicing gratitude can…

6. Make people like us

Those who are more grateful have access to a wider social network, more friends, and better relationships on average (Amin, 2014). This is likely because of the effect that being grateful has on how trustworthy, social, and appreciative we seem to others.

7. Improve our romantic relationships

A recent study found evidence that expressing gratitude to our significant others results in improved quality in the relationship (Algoe, Fredrickson, & Gable, 2013). Showing our gratitude to loved ones is a great way to make them feel good, make us feel good, and make the relationship better in general!

8. Improve our friendships

Similar to the effects of gratitude on romantic relationships, expressing gratitude to our friends can improve our friendships. Those who communicate their gratitude to their friends are more likely to work through problems and concerns with their friends and have a more positive perception of their friends (Lambert & Fincham, 2011).

9. Increases social support

Unsurprisingly, given the other social benefits of gratitude, those who are more grateful have access to more social support. The same study that confirmed this finding reported that higher gratitude also leads to lower levels of stress and depression, suggesting that gratitude not only helps you get the social support you need to get through difficult times, but it lessens the need for social support in the first place (Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008)!

10. Strengthen family relationships in times of stress

Gratitude has been found to protect children of ill parents from anxiety and depression, acting as a buffer against the internalization of symptoms (Stoeckel, Weissbrod, & Ahrens, 2015). Teenage and young adult children who are able to find the positives in their lives can more easily deal with difficult situations like serious illness in the family.

Gratitude and Personality Benefits

Here are a few things gratitude has been found to impact. Gratitude can…

11. Make us more optimistic

Showing our gratitude not only helps others feel more positively, it also makes us think more positively. Regular gratitude journaling has been shown to result in 5% to 15% increases in optimism (Amin, 2014), meaning that the more we think about what we are grateful for, the more we find to be grateful for!

12. Increase our spiritualism

If you are feeling a little too “worldly” or feeling lost spiritually, practicing gratitude can help you get out of your spiritual funk. The more spiritual you are, the more likely you are to be grateful, and vice versa (Urgesi, Aglioti, Skrap, & Fabbro, 2010).

13. Make us more giving

Another benefit to both ourselves and others, gratitude can decrease our self-centeredness. Evidence has shown that promoting gratitude in participants makes them more likely to share with others, even at the expense of themselves, and even if the receiver was a stranger (DeSteno, Bartlett, Baumann, Williams, & Dickens, 2010).

14. Indicate reduced materialism

Unsurprisingly, those who are the most grateful also tend to be less materialistic, likely because people who appreciate what they already have are less likely to fixate on obtaining more. It’s probably also not a surprise to learn that those who are grateful and less materialistic enjoy greater life satisfaction (Tsang, Carpenter, Roberts, Frisch, & Carlisle, 2014).

15. Enhance optimism

A study on the effects of gratitude on positive affectivity and optimism found that a gratitude intervention resulted in greater tendencies towards positivity and an expanded capacity for happiness and optimism (Lashani, Shaeiri, Asghari-Moghadam, & Golzari, 2012).

Gratitude and Career Benefits

Of course, many of the social, emotional, and personality benefits of regularly practicing gratitude can carry over to affect work life as well, but some effects are seen primarily over the course of daily work.

In the workplace, gratitude can…

16. Make us more effective managers

Gratitude research has shown that practicing gratitude enhances your managerial skills, enhancing your praise-giving and motivating abilities as a mentor and guide to the employees you manage (Stone & Stone, 1983).

17. Reduce impatience and improve decision-making

Those that are more grateful than others are also less likely to be impatient during economic decision-making, leading to better decisions and less pressure from the desire for short-term gratification (DeSteno, Li, Dickens, & Lerner, 2014). As anyone who has ever worked a stressful job already knows, decisions made to satisfy short-term urges rarely provide positive work results or a boost to your career!

18. Help us find meaning in our work

Those who find meaning and purpose in their work are often more effective and more fulfilled throughout their career. Gratitude is one factor that can help people find meaning in their job, along with applying their strengths, positive emotions and flow, hope, and finding a “calling” (Dik, Duffy, Allan, O’Donnell, Shim, & Steger, 2015).

19. Contribute to reduced turnover

Research has found that gratitude and respect in the workplace can help employees feel embedded in their organization, or welcomed and valued (Ng, 2016). This is especially important in the early stages of a career when new employees are still finding their way and are less likely to be afforded respect from their older or more experienced peers.

20. Improve work-related mental health and reduce stress

Employing gratitude at work can have a significant impact on staff mental health, stress, and turnover. In a rigorous examination of the effects of gratitude on stress and depressive symptoms in hospital staff, researchers learned that the participants randomly assigned to the gratitude group reported fewer depressive symptoms and stress (Cheng, Tsui, & Lam, 2015). Finding things to be grateful for at work, even in stressful jobs, can help protect staff from the negative side effects of their job.

Gratitude and Physical Health

For example, it has been shown that gratitude can…

21. Reduce depressive symptoms

A study on gratitude visits showed that participants experienced a 35% reduction in depressive symptoms for several weeks, while those practising gratitude journaling reported a similar reduction in depressive symptoms for as long as the journaling continued (Seligman et al., 2005). This is an amazing finding and suggests that gratitude journaling can be an effective supplement to treatment for depression.

22. Reduce your blood pressure

Patients with hypertension who “count their blessings” at least once a week experienced a significant decrease in blood pressure, resulting in better overall health (Shipon, 1977). Want a healthy heart? Count your blessings!

23. Improve your sleep

A two-week gratitude intervention increased sleep quality and reduced blood pressure in participants, leading to enhanced wellbeing (Jackowska, Brown, Ronaldson, & Steptoe, 2016). If you’re having trouble sleeping or just waking up feeling fatigued, try a quick gratitude journaling exercise before bed – it could make the difference between groggy and great in the morning!

24. Increase your frequency of exercise

It’s true: being grateful can help you get fit! It may not be a very effective “fast weight loss” plan, but it has been shown that study participants who practiced gratitude regularly for 11 weeks were more likely to exercise than those in the control group (Emmons & McCullough, 2003).

25. Improve your overall physical health

Evidence shows that the more grateful a person is the more likely he or she is to enjoy better physical health, as well as psychological health (Hill, Allemand, & Roberts, 2013). Apparently, grateful people are healthy people!

Gratitude’s Role in Recovery

Whether the issue is substance abuse or a physical ailment, gratitude might be able to help those who are suffering to take control of their lives and get well again.

Gratitude may…

26. Help people recover from substance misuse

Researchers and addiction programs alike have noticed that gratitude can play a key role in recovery from substance misuse or abuse. It seems to help by enabling the development of strengths and other personal resources that individuals can call on in their journey towards a healthier life (Chen, 2017).

27. Enhance recovery from coronary health events

A study out of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital found that acute coronary syndrome patients experienced greater improvements in health-related quality of life and greater reductions in depression and anxiety when they approached recovery with gratitude and optimism (Millstein, Celano, Beale, Beach, Suarez, Belcher, … & Huffman, 2016).

28. Facilitate the recovery of people with depression

A case study of a woman with depression revealed that the adoption of Buddhist teachings and practices, with a strong emphasis on utilizing gratitude as a recovery tool, helped her to heal (Cheng, 2015). This should be taken with a grain of salt as a case study, but there is also plenty of evidence that techniques and exercises drawn from Buddhist teachings can have profound benefits for those who practice them.

Related: Gratitude Meditation: A Simple But Powerful Happiness Intervention.

Robert Emmons: the power of gratitude – Greater Good Science Center

The Most Important Gratitude Research Articles

These three articles are some of the most important pieces of gratitude research that you should familiarize yourself with if you would like to know more about the state of our knowledge on gratitude’s precursors, mediators, and impacts.

Emmons & McCullough: Counting Blessings

This article was already mentioned a few times in the section on the benefits of gratitude, and for good reason. Emmons and McCullough’s (2003) work was groundbreaking and has set the stage for much of the research that has been conducted since it was published.

Their article, titled “Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective wellbeing in daily life,” describes three studies conducted to explore the potential emotional and interpersonal benefits of gratitude.

Study 1

Study 1 involved a group of around 200 undergraduate students, split into one gratitude group, one “hassles” group, and one neutral control group. The gratitude group received instructions to think back over their past week and write down up to five things they were grateful for in their life. The hassles group was instructed to write down up to five hassles or irritants they had experienced over the past week. The control group indicated up to five events that had an impact on them over the last week.

The students completed these “weekly reports” for 10 weeks, along with items assessing wellbeing, physical symptoms, reactions to aid or help-giving, and appraisals of their overall state. Results from this study showed that participants in the gratitude group felt better about their life on the whole, more optimistic about the upcoming week, and reported fewer physical complaints than participants in the other groups.

Study 2

In study 2, a sample of about 160 undergraduate students in a health psychology class completed 16 “daily experience rating forms.” These rating forms were nearly identical to the forms from study 1 but referenced the daily time period instead of the previous weekly time period. The first two groups were also given the gratitude and hassles instructions, respectively, but the third group was instructed to write about the ways in which they were better off than others. This was dubbed the “downward social comparison” group.

Participants also indicated the frequency with which they exercised, the number of hours of sleep they got the previous night, and whether they had engaged in prosocial behaviors each day.

Results from study 2 showed that those in the gratitude group reported greater positive affect and more prosocial behavior than participants in the other groups, although there was no significant difference found in the frequency of exercise or amount of sleep.

Study 3

Study 3 was conducted with a group of adults who suffered from a neuromuscular disease. They completed a packet of 21 daily experience rating forms similar to those employed in study 2. Participants were assigned to either the gratitude group, where they were given the same instructions as the gratitude group in the previous studies and completed measures of daily affect, wellbeing, and other health and daily living activities, or the control group, in which participants completed only the measures portion of the daily tasks.

The findings from study 3 showed that those in the gratitude condition reported increased subjective wellbeing, greater positive affect, and more hours of quality sleep. Ratings from the participants’ significant others confirmed that there was a noticeable difference in their wellbeing as well.

These three studies provided evidence that gratitude can have a significant impact on an individual’s emotional, mental, and possibly even physical state. While there had been other explorations of gratitude as a psychological construct, this was one of the first articles suggesting that the benefits of gratitude may be far greater than we realized at the time.

If you remember anything about this article, remember this: Emmons and McCullough (2003) showed that counting your blessings seems to be a much more effective way of enhancing your quality of life than counting your burdens.

Bartlett & DeSteno: Gratitude and Prosocial Behavior

The previous studies had hinted at this relationship, but Bartlett and DeSteno made this relationship their main focus in their 2006 article.

This article also consists of three studies:

Study 1

Study 1 paired 105 individuals with a study confederate, an actor complicit with the researchers who the participants believed was just another study participant. They completed tasks independently but side by side, although the participant was under the impression that their work would contribute to a single score for both of them.

After these tasks, including a general knowledge task and a hand-eye coordination task, the next activity depended upon the participant’s randomly assigned condition.

Some participants were assigned to the gratitude condition, in which the study confederate was secretly complicit with researchers in introducing a problem with the participant’s task completion. The confederate would help the participant figure out the problem, saving him or her time and effort on redoing their tasks.

Some participants were placed in the amusement group, where they would watch a humorous video clip after completing the tasks and be engaged in conversation about the clip by the confederate. Afterward, they were given a meaningless task of checking off which words from a list had appeared in the clip.

The rest of the participants were assigned to the control group, in which the confederate briefly engaged the participant in the conversation about where the experimenter might be, before “finding” him or her, at which point the next tasks were introduced.

After the activities of the above conditions, participants completed a questionnaire designed to assess their emotional state and feelings towards their “partner” (i.e., the confederate). Once the questionnaire was completed, participants were also approached by the confederate once again, this time with a request to fill out a long and effort-intensive survey the confederate was ostensibly handing out for her work-study advisor.

The experimenter noted how long the participant worked on this survey, coding a refusal to take the survey as 0 minutes.

Results from this study showed that those in the gratitude condition were more likely to help the confederate, and their efforts lasted longer than the efforts of those in the other conditions, on average. This was the expected outcome of the study, as the researchers predicted that participants with a reason to be grateful to their “peer” would be more willing to help them out with a completely voluntary (and boring) task.

Study 2

In study 2, 97 participants completed nearly the exact same process as described in study 1, but with two differences:

1) The amusement condition was dropped.

2) Another factor was added in; in one condition, the person asking for help was the confederate who the participant thought was a peer, while in the other condition a stranger (also supposedly a participant, but not one the participant had actually spoken to) requested help.

The results of this study showed that participants who were approached for help by the friendly confederate were more likely to agree to complete the survey than those who were approached by a stranger, regardless of whether they were in the gratitude group or the control group. However, those in the gratitude group who were approached by a stranger for help were still more likely to agree than those in the control group who were approached by a stranger.

These findings suggest that the gratitude manipulation really does encourage people to be prosocial, although it’s more likely that they will want to help the individual they are specifically grateful to than strangers.

Study 3

Finally, in study 3, 35 participants completed nearly the same process as described in study 2, except:

1) Instead of employing a confederate and a stranger to alternate requests for help, study 3 used only a stranger for the request.

2) Another condition was included, dubbed the “gratitude-source” condition, in which the usual gratitude group process included a brief encounter with the experimenter before leaving the lab and being approached for help from a stranger. The experimenter asked “Was it the other participant who figured out what was wrong with your computer?”, drawing attention to the source to which the participant should be grateful.

The results of study 3 provide showed that participants in the gratitude condition helped the stranger significantly more than those in the neutral and gratitude-source conditions, indicating that gratitude not only enhances prosocial behavior, but the effect is present without the coercion of a norm of reciprocity (i.e., feeling that you must pay it forward because you have received).

This article was important because it solidified the theoretical link between gratitude and prosocial behaviors, indicating that those who are more grateful are more likely to engage in voluntary helping behaviors. This is an important link to understand, and one that can have very positive impacts when applied to our communities (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006).

The main point from this paper is that gratitude can evoke positive effects, even for those who were neither the one who was grateful nor the one on the receiving end of the gratitude.

A small act of gratitude can cause ripple effects that reach farther than you would imagine.

Increasing and Sustaining Positive Emotion through Gratitude

This article made a major contribution to the research surrounding gratitude and positive affect, and the relationship between the two.

This study was conducted as a four-week longitudinal exploration of what happens when people regularly practice two popular happiness strategies. The participants were a group of 67 undergraduate students who were split into three experimental groups:

- The first group was assigned to the gratitude exercise, otherwise known as the “counting your blessings” exercise (this exercise was used in McCullough and Emmons’ 2003 research!). These participants completed this exercise, instructing them to think about the things in their life that they are grateful for and to continue to do so over the next few weeks.

- The second group received instructions for the “best possible selves” exercise. In this exercise, participants are instructed to visualize their best possible selves, now and during the next few weeks. They imagine their future if everything in life has gone as well as it possibly could, and they have met all of their important goals, and are told to continue this visualization over the next few weeks.

- The third group, or the “life details” group, was instructed to “pay more attention” to their lives. They were encouraged to think about all the details they usually don’t notice, regarding their classes or regular meetings they attend, interactions they engage in with others, and their typical schedule as they move through the day. They are also told to continue paying more attention to their life over the next few weeks.

After participants in each group finished their assigned exercises, they completed a mood questionnaire, a mental exercise, a second mood questionnaire, and a rating of their motivation to keep engaging in their assigned exercise in the near future. The questionnaires included a well-known scale of affect, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, or PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988).

Participants completed these exercises and measurements at a small-group laboratory session and completed online surveys approximately two weeks and four weeks after the session to in which they reported their mood and indicated how well frequently they were actually performing the exercise.

The results of this study showed that each condition reported immediate reductions in negative affect, but that only the “best possible selves” group experienced a significant increase in positive affect. In addition, participants in this condition reported the greater motivation and interest in continuing this exercise outside of the lab.

Those who reported higher motivation were also more likely to follow through on their exercise. Completing the exercise more faithfully also resulted in a more positive mood in the follow-up assessments, especially for those in the “best possible selves” group (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2007).

These findings showed two important things, among others:

1) A regular practice of gratitude and/or positive visualization can lead to a higher quality of life, measured by affect.

2) It can be difficult to motivate people to consistently practice gratitude.

It seems counterintuitive that we are often so resistant to doing something that can make our lives objectively better, but that’s the truth: it’s hard to cultivate a regular gratitude practice.

Towards this end, it may be useful to measure your own levels of gratitude. You may find that you have room to improve in this area, in which case you may want to try a gratitude exercise or institute a regular practice of being grateful. The measures below can help you with this goal.

Related: The 20 Best TED Talks And Videos on The Power of Gratitude

Measuring Gratitude with Questionnaires and Scales

As with any psychological construct, there are many different ways to measure it. The three measures that are most popular and most used in research are listed and described here.

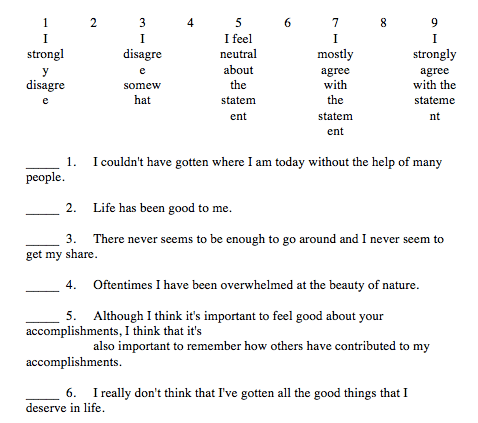

The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test (GRAT)

This measure was developed in 2003 by researchers from Eastern Washington University, and

provides a measure of trait gratitude (i.e., the more permanent type of gratitude that is ingrained in your personality).

It includes 44 items representing characteristics that a grateful person tends to exhibit.

To complete the measure, you simply indicate how much you agree or disagree with each statement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). Some of these statements are decidedly not indicative of a grateful person, but not to worry – these are reverse scored, so a “strongly agree” would be a 1 on this item instead of a 9.

The total score represents the survey taker’s overall level of trait gratitude, which has been shown to correlate with subjective wellbeing and positive affect (Watkins, Woodward, Stone, & Kolts, 2003).

Some sample items include:

- “I think it’s important to enjoy the simple things in life.”

- “More bad things have happened to me in my life than I deserve.” (reverse-scored)

- “I think that it’s important to sit down every once in a while and “count your blessings.”

- “I believe that I’ve had more than my share of bad things come my way.” (reverse-scored)

You can see multiple versions of the GRAT at this link.

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6)

This scale is a stunningly simple one, with only six items to rate. It was developed by Emmons, McCullough, and their colleague Tsang, and used in their 2002 article on gratitude and the “grateful disposition.”

The statements are rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with two reverse-scored items. The total score is added up from each item, and indicates your “GQ-6 score.” The number will be between 6 and 42, with higher numbers indicating a more grateful outlook on life.

The six items are as follows:

- “I have so much in life to be thankful for.”

- “If I had to list everything that I felt grateful for, it would be a very long list.”

- “When I look at the world, I don’t see much to be grateful for.” (reverse-scored)

- “I am grateful to a wide variety of people.”

- “As I get older I find myself more able to appreciate the people, events, and situations that have been part of my life history.”

- “Long amounts of time can go by before I feel grateful to something or someone.” (reverse-scored)

As a benchmark for comparing your score to others, if you scored below a 35 out of the possible 42, your gratitude level is in the bottom 25% of participants. If you scored a 42, you are in the top 13% of participants.

Whatever your score is, don’t worry too much about it – just see what you can do to be more grateful for what you have, and watch your wellbeing expand because of it!

Gratitude Adjective Checklist (GAC)

Because it is not tied down by a time frame, it can be used to measure gratitude in any form, whether you are viewing it more as an emotion, a mood, or a trait.

The Gratitude Adjective Checklist is even simpler than the GQ-6. It consists of only three adjectives, and participants rate the intensity with which they are experiencing these adjectives on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

These adjectives are:

- “Appreciative”

- “Grateful”

- “Thankful”

A total score is calculated by simply adding the ratings on these three adjectives. The score can range from 3 to 15, with 3 indicating the lowest possible levels of gratitude and 15 indicating the highest possible level of gratitude.

As simple as it is, it has been found to be reliable and internally consistent and is used frequently in research, although not as often as the GRAT and the GQ-6.

You can find out more about measuring gratitude, scales and questionnaires here.

A Take-Home Message

As always, I sincerely hope that you both enjoyed this piece and learned a little something from it.

Please remember to cultivate gratitude in your life whenever you can. You never know how far the impacts of a little gratitude can reach!

What do you think of these gratitude benefits? Have you experienced any yourself? Do you have any other suggestions for important gratitude research articles to share? Let us know in the comments!

For further reading:

- 5 Best Books on Gratitude + Oliver Sacks’ Gratitude Book

- Gratitude Messages, Letters and Lists

- The Gratitude Tree for Kids (Incl. Activities + Drawings)

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Gratitude Exercises for free.

- Algoe, S. B., Fredrickson, B. L., & Gable, S. L. (2013). The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion, 13, 605-609.

- Amin, A. (2014). The 31 benefits of gratitude you didn’t know about: How gratitude can change your life. Happier Human. Retrieved from http://happierhuman.com/benefits-of-gratitude/

- Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior. Psychological Science, 17, 319-325.

- Chen, G. (2017). Does gratitude promote recovery from substance misuse? Addiction Research & Theory, 25, 121-128.

- Cheng, F. K. (2015). Recovery from depression through Buddhist wisdom: An idiographic case study. Social Work in Mental Health, 13, 272-297.

- Cheng, S., Tsui, P. K., & Lam, J. M. (2015). Improving mental health in health care practitioners: Randomized controlled trial of a gratitude intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 177-186.

- DeSteno, D., Bartlett, M. Y., Baumann, J., Williams, L. A., & Dickens, L. (2010). Gratitude as moral sentiment: Emotion-guided cooperation in economic exchange. Emotion, 10, 289-293.

- DeSteno, D., Li, Y., Dickens, L., & Lerner, J. S. (2014). Gratitude: A tool for reducing economic impatience. Psychological Science, 25, 1262-1267.

- Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., O’Donnell, M. B., Shim, Y., & Steger, M. F. (2015). Purpose and meaning in career development applications. The Counseling Psychologist, 43, 558-585.

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377-389.

- Hill, P. L., Allemand, M., & Roberts, B. W. (2013). Examining the pathways between gratitude and self-rated physical health across adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 92-96.

- Jackowska, M., Brown, J., Ronaldson, A., & Steptoe, A. (2016). The impact of a brief gratitude intervention on subjective well-being, biology and sleep. Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 2207-2217.

- Krysinska, K., Lester, D., Lyke, J., & Corveleyn, J. (2015). Trait gratitude and suicidal ideation and behavior: An exploratory study. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 36, 291-296.

- Lambert, N. M., & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Expressing gratitude to a partner leads to more relationship maintenance behavior. Emotion, 11, 52-60.

- Lashani, Z., Shaeiri, M. R., Asghari-Moghadam, M. A., & Golzari, M. (2012). Effect of gratitude strategies on positive affectivity, happiness and optimism. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 18, 164-166.

- Lin, C. (2017). The effect of higher-order gratitude on mental well-being: Beyond personality and unifactoral gratitude. Current Psychology, 36, 127-135.

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

- Millstein, R. A., Celano, C. M., Beale, E. E., Beach, S. R., Suarez, L., Belcher, A. M., & … Huffman, J. C. (2016). The effects of optimism and gratitude on adherence, functioning and mental health following an acute coronary syndrome. General Hospital Psychiatry, 43, 17-22.

- Ng, T. H. (2016). Embedding employees early on: The importance of workplace respect. Personnel Psychology, 69, 599-633.

- Rash, J. A., Matsuba, M. K., & Prkachin, K. M. (2011). Gratitude and well‐being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3, 350-369.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening, 42, 874-884.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 73-82.

- Shipon, R. W. (1977). Gratitude: Effect on perspectives and blood pressures of inner-city African-American hypertensive patients. US: ProQuest Information & Learning. Accession Number: 2007-99018-513.

- Stoeckel, M., Weissbrod, C., & Ahrens, A. (2015). The adolescent response to parental illness: The influence of dispositional gratitude. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1501-1509.

- Stone, D. I., & Stone, E. F. (1983). The effects of feedback favorability and feedback consistency. Academy of Management Proceedings (00650668), 178-182.

- Tsang, J., Carpenter, T. P., Roberts, J. A., Frisch, M. B., & Carlisle, R. D. (2014). Why are materialists less happy? The role of gratitude and need satisfaction in the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 64, 62-66.

- Urgesi, C., Aglioti, S. M., Skrap, M., & Fabbro, F. (2010). The spiritual brain: Selective cortical lesions modulate human self-transcendance. Neuron, 65, 309-319.

- Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 31, 431-451.

- Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070.

- Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 854-871.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

What a terrific resource! Thank you, Courtney! I have run a GRATITUDE community on Facebook for the past 8 years called “Attitude of Gratitude with Chronic Pain.” We use the tools of a regular GRATITUDE practice and our group connection to help us to recover from the emotional debilitation we have from living with chronic pain/illness. We have 8,000 members who all join us knowing that we are a very different group in that we don’t talk about the specifics of our conditions and we are positive/solution-based. Every day I have people telling me that our group and a regular GRATITUDE practice has dramatically improved the quality of their lives! I’m currently writing a book on the subject and am GRATEFUL to find this amazing resource! I have done much research over the years on the effects of GRATITUDE on living with chronic pain and have seen the benefits myself. I firmly believe that sharing our GRATITUDE in a group setting within our community strengthens the benefits, and I have had researchers point out that this has been proven (Dr. Fuschia Sirois from U of Sheffield, UK).

Love, Love, Love! Be Grateful in everything.

I love the research on the connection between gratitude and the body. I’ve personally found that having gratitude for my body makes me want to take better care of it (via movement, nourishment, etc.). Thanks for sharing!

This is such a meaningful and beautiful article. Enjoyed reading it and lots to take home and use in everyday life. Thank you.

very informative and useful article to apply in our life

Thanks for sharing the information. I have started expressing gratitude on regular basis after reading this article and I can see drastic positive changes in my life. Thanks once again.

Thank you for this very informative piece which I will refer to in my work and share with my family. I grew up in India in a family where gratitude was a core family value. As a result, I have embodied it my daily life and have found it to be magical in living life with purpose, being positive, cultivating resiliency amidst life’s challenges and being able to make a difference in my personal and professional life across cultural, racial and gender stereotyping divides.

Hi Courtney

Well done for your work and I am very grateful that I came across it. I find it useful to have some formal research verify a positive practice that can enhance one’s life.-especially when promoting the process to others. One does not need to engage in journaling on a daily basis, as an ongoing practice. However, one can take the time each day -even for a quick thought on the run- to mentally relate one thing to be grateful for. This helps develop a pattern in order to help change the brain wiring and firing-until it becomes a joyful habit. So thank you and I wish you all the best in your future studies.

Great work. I found the article useful as it is enriched with comprehensive information presented systematically with references.