What is Job Crafting? (Incl. 5 Examples and Exercises)

What would your ideal work day look like? How would you describe your current job? Is it “another day another dollar”? Maybe “thank goodness it’s Friday?” Or, is it more “I love what I do!”

What would your ideal work day look like? How would you describe your current job? Is it “another day another dollar”? Maybe “thank goodness it’s Friday?” Or, is it more “I love what I do!”

If it’s one of the first two, you’re not alone. Stress and burnout are super popular topics in wellbeing literature, especially as the pace of competition creates new challenges for us at work.

Meetings, commutes, emails, and so forth arguably take their toll and can leave us wondering whether we’re paid enough to warrant it all. Living to work isn’t ideal, but working just to live is not an attractive concept, either.

So, the idea that we can find and create more meaning and happiness through our work is an appealing one. But how do we go about it? In this article, we’ll look at the how and the what of job crafting, which all stems inextricably from the ‘why’ of our working lives.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify opportunities for professional growth and create a more meaningful career.

This Article Contains:

- What is Job Crafting? (Incl. Definition)

- A Look at the Job Crafting Model

- 5 Examples of Job Crafting

- Positive Psychology and Job Crafting: Meaningful Work

- 5 Benefits of the Approach

- Are there Drawbacks?

- The Job Crafting Questionnaire (PDF)

- The Job Crafting Intervention

- The Job Crafting Exercise

- The Fatima Job Crafting Case Study

- Job Crafting Workshops

- Books on the Topic

- 5 Recommended Videos

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Job Crafting? (Incl. Definition)

During the week, most of us spend half our waking hours at work. And a lot of us see it as a struggle, or at least a bore, looking forward to the weekend when we can do more worthwhile things. But what if your job itself was worthwhile? What if it was meaningful, left you satisfied, and through it, you could be part of something bigger?

The ‘Why’ of Job Crafting

Job crafting is about taking proactive steps and actions to redesign what we do at work, essentially changing tasks, relationships, and perceptions of our jobs (Berg et al., 2007). The main premise is that we can stay in the same role, getting more meaning out of our jobs simply by changing what we do and the ‘whole point’ behind it.

So through the techniques and approaches that we’ll look at in this article, we ‘craft’ ourselves a job that we love. One where we still can satisfy and excel in our functions, but which is simultaneously more aligned with our strengths, motives, and passions (Wrzesniewski et al., 2010). Unsurprisingly, it has been linked to better performance (Caldwell & O’Reilly, 1990), intrinsic motivation, and employee engagement (Halbesleben, 2010; Dubbelt et al., 2019).

Job Crafting Definitions

In one sense, then, job crafting is:

“an employee-initiated approach which enables employees to shape their own work environment such that it fits their individual needs by adjusting the prevailing job demands and resources”

(Tims & Bakker, 2010)

However, really great organizational development always starts with the ‘Why’, so here is another definition:

[Job crafting] is proactive behavior that employees use when they feel that changes in their job are necessary.

(Petrou et al., 2012)

3 Key Types of Job Crafting

So how do we go about it? In three possible ways, says Professor Amy Wrzesniewski, who first introduced the concept with Jane Dutton in 2001. These are task crafting, relationship crafting, and/or cognitive crafting, and they describe the ‘behaviors’ that employees can use to become ‘crafters’. Through one or more of these activities, we can aim to create the job-person fit that might be lacking in our current roles (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Task Crafting: Changing up responsibilities

Task crafting may be the most discussed aspect of the approach, perhaps because job crafting is commonly seen as active ‘shaping’ or ‘molding’ of one’s role. It can involve adding or dropping the responsibilities set out in your official job description (Berg et al., 2013).

For instance, a chef may take it upon themselves to not just serve food but to create beautifully designed plates that enhance a customer’s dining experience. As another example, a bus driver might decide to give helpful sightseeing advice to tourists along his route.

This type of crafting might also (or alternatively) involve changing the nature of certain responsibilities, or dedicating different amounts of time to what you currently do. As we’ll see in some of the examples below, this doesn’t necessarily affect the quality or impact of what you’re hired to do.

Relationship Crafting: Changing up interactions

This is how people reshape the type and nature of the interactions they have with others. In other words, relationship crafting can involve changing up who we work with on different tasks, who we communicate and engage with on a regular basis (Berg et al., 2013). A marketing manager might brainstorm with the firm’s app designer to talk and learn about the user interface, unlocking creativity benefits while crafting relationships.

Cognitive Crafting: Changing up your mindset

The third type of crafting, cognitive crafting, is how people change their mindsets about the tasks they do (Tims & Bakker, 2010). By changing perspectives on what we’re doing, we can find or create more meaning about what might otherwise be seen as ‘busy work’. Changing hotel bedsheets in this sense might be less about cleaning and more about making travelers’ journeys more comfortable and memorable.

Through one, two, or all of the above, job crafting proponents argue that we can redefine, reimagine, and get more meaning out of what we spend so much time doing.

Job Design vs Job Crafting

If you’re interested in organizational psychology, you might be wondering what the differences are between the job design and job crafting. There are indeed similarities between the former and ‘task crafting’, as job design involves systematic organization of work-related processes, functions, and tasks (Garg & Rastogi, 2006).

Both task crafting and job design can involve task revision, where responsibilities are added or dropped to change the nature of your role. Both also stem from the premise that job dimensions can impact our experienced meaningfulness, growth, intrinsic motivation, and job satisfaction (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; 1980).

Even job sharing under the job characteristics model can be seen as a type of relationship crafting in some respects, but in most cases, job design is seen as a ‘top-down’ organizational approach in which the worker is mostly passive (Makul et al., 2013; Miller, 2015).

In contrast, job crafting puts the responsibility for change in employees’ hands. Workers are proactive and the approach is first and foremost about enhancing their wellbeing (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Tims et al., 2013). Arguably, this gives rise to potential drawbacks for the organization—even for the employee in question—and we’ll cover these limitations in this article, too.

A Look at the Job Crafting Model

To be fair, there is more than one job crafting model. In fact, there are at least two important frameworks that are being developed and further developed as we learn more about the discipline as a whole. These are the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model, and the Job Crafting Model.

First, we know that a proactive approach is an important precursor for job crafting. But what else do we need to boost our chances of success? From a theoretical perspective, we need to know a bit about job demands and resources, and the Job Demands-Resources Model is very useful.

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model

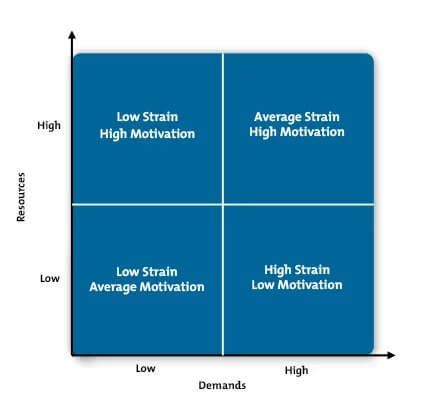

Bakker and Demerouti’s (2007) JD-R Model is about job characteristics. In short, it views all the characteristics of our jobs—psychological, physical, organizational, and social aspects—as either demands or resources.

- Job demands require that we put in physical or psychological effort or skills; they ‘cost’ us something. Emotional strain and similar are popular examples of job demands, which can lead to costs like stress, burnout, and related stressors when they become extreme (Bakker et al., 2003; Bakker & Demerouti, 2008).

- Job resources help us accomplish our work goals and we can draw on these facilitators to counter the potentially negative impacts of job demands. They can be made available by organizations or they can be personal, respectively these are workplace resources or personal resources. The first would entail aspects like career prospects, training, and autonomy, and examples of the second include optimism and self-efficacy (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008).

When we think about job crafting from a positive psychology perspective, we’re looking at how we can foster or facilitate positive emotions. According to the JD-R model, we can do this in at least two ways:

- First, by upping our job resources – We might use relationship crafting, for instance, to increase our social resources. Another example is to add to our structural resources (training, autonomy, etc) through task crafting.

- Second, by increasing our job demands – to a pleasantly challenging extent. Think eustress or ‘stretch zone’ challenges rather than vanilla stress.

The ultimate goal of the JD-R model is to allow for an understanding of how demands and resources interact to impact our motivation, as shown below.

Source: Mindtools.com

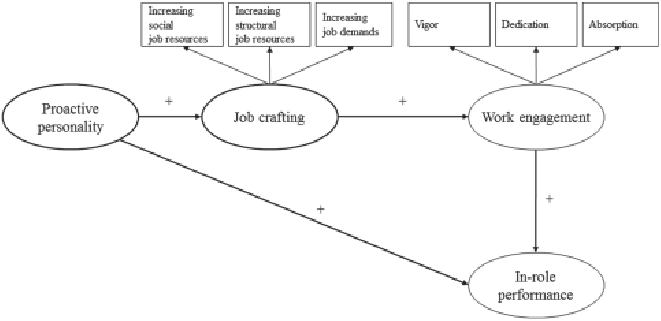

The Job Crafting Model

It’s when we consider job crafting that proactivity comes into the equation, and in Bakker et al.’s (2012) study, we first see The Job Crafting Model as a framework. In their research, they found that proactive personalities were positively related to job performance, through work engagement and job crafting. The exact relationships they found are shown in the Job Crafting Model below (Bakker et al., 2012).

Source: Bakker et al. (2012)

Their study also found that:

- Employees with proactive personalities were more likely to be involved in job crafting;

- This promoted greater engagement at work, by facilitating alignment between job resources, job demands, personal needs, and their own capabilities; and

- Employees who increased their structural resources, social resources and specific aspects of their job demands received higher performance ratings, according to their co-workers.

There is one key limitation of this study for those interested in cognitive crafting; this particular aspect of the three key types wasn’t examined (Berg et al., 2013).

5 Examples of Job Crafting

It’s in Berg and colleagues’ (2010) article that we’re given some super insight into job crafting—in action.

This paper is worth a read if you’re keen to get more of a feel for the approach.

1. Task Crafting

“I really enjoy online tools and Internet things…So I’ve really tailored that aspect of the written job description, and really ‘‘upped’’ it, because I enjoy it…it gives me an opportunity to play around…explore tools and web applications, and I get to learn, which is one of my favorite things…” (Berg et al., 2010: 166)

Just to recap, task crafting can be adding resources through extra tasks, while some might [also] choose to change what they’re currently doing. One interviewee, an associate who worked for a non-profit, stepped up the amount of time she spent working with online applications. In this way, she was engaging her passion for learning, allocating the proportion of time she spends on a specific aspect, and making it all the more meaningful.

2. Relationship Crafting

“I have taken the initiative to form relationships with some of the folks who fulfill orders…That’s not my area, but I was really interested in how that worked and wanted to learn…I have learned a lot from them, and that’s helped me in my job.” (Berg et al., 2010: 166)

Above, a customer service rep describes creating additional relationships with co-workers. While building up the way he interacts with others, he’s expanding his social job resources and gaining knowledge. As he later describes, this helps him explain the fulfillment process to customers directly.

3. Cognitive Crafting

“Technically, [my job is] putting in orders, entering orders, but really I see it as providing our customers with an enjoyable experience, a positive experience, which is a lot more meaningful to me than entering numbers.” (Berg et al., 2010: 167)

Here, a different customer service representative recounts going above and beyond to enhance the client experience. This perspective shift sees the employee reframing their job as part of ‘something bigger’, both within the organizational context and for society in general. We can see a holistic perspective that has been shaped; this individual is no longer viewing their job as separate, unconnected tasks, but as a ‘meaningful whole’ (Berg et al., 2010).

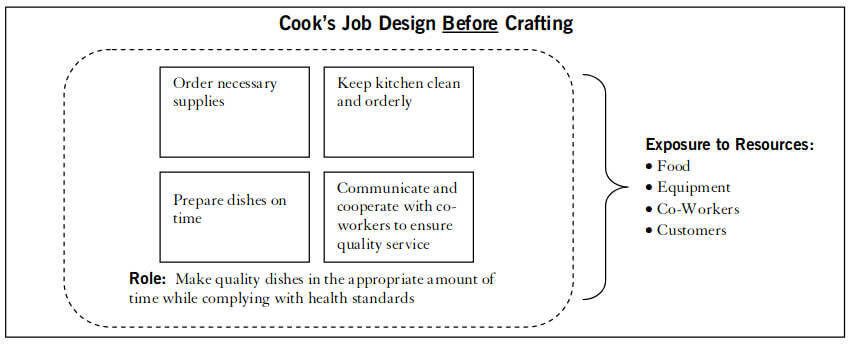

4. From Cook to Creative Artist

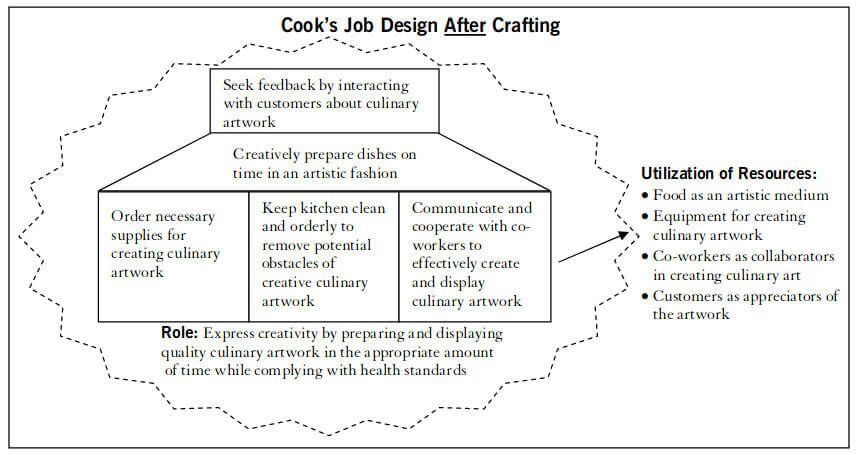

Putting it all together, here’s one nice example of job crafting given by Berg and colleagues (2007). Before crafting, this cook’s job consists of—or at least, is perceived by the cook as—separate tasks, very much segmented as they would be in a formal job description. Job resources here are not inherently meaningful other than as facilitators for accomplishing the tasks, and one could argue that the role in question is almost defined by its boundaries.

Source: Berg et al. (2007: 6)

After job crafting, we can see evidence of all three approaches at work:

- The chef’s perspectives are altered fundamentally—food has become culinary artwork, bringing her a whole new sense of purpose. In other words, it’s not hard to guess where this chef’s passions lie; she has cognitively crafted himself a new role as a culinary artisan.

- In this newly reframed context, tasks are meaningfully linked—both to one another and to the larger context. We see job resources taking on new meaning: food is not just that, but a means of personal creative expression. New tasks are added, expanding the boundaries of her role.

- Customers also take on new meaning as feedback providers, so the chef can potentially grow and improve her skills. At the same time, relationship crafting sees her interactions with co-workers becoming more collaborative. Perhaps through this, there’s knowledge transfer as well as increased use of her social resources.

Source: Berg et al. (2007: 6)

5. The Pink Glove Dance

Last but not least, here’s another lovely example of job crafting in (musical) action—The Pink Glove Dance is essentially personal meaning being created by hospital employees. In this video, you’ll see cleaners, janitors, clerks, and other hospital staff linking ‘what they do’ on the job with who they are and their commitment to raising awareness of breast cancer (Harquail, 2009). What do you think?

Positive Psychology and Job Crafting: Meaningful Work

Throughout this whole article, we’ve been looking at job crafting as a way to create meaning in our roles. Succinctly, ‘meaningfulness’ describes how much significance we attribute to our work (Rosso et al., 2010). It’s one of five key concepts in Seligman’s PERMA model, and he defines it as,

“using your signature strengths and virtues in the service of something much larger than you are”

(Seligman, 2004: 294)

By creating or finding more meaning in our work, positive psychology would say that we’re increasing our happiness. And in the empirical literature, there is ample evidence that meaningfulness does play out well in the workplace—as enhanced job satisfaction, performance, and motivation (Hackman & Oldman, 1980; Rosso et al., 2010).

5 Benefits of the Approach

Job crafting presents lots of potential benefits for organizational and positive psychology practitioners. While still relatively young, the approach has been examined empirically. Among the findings, and in addition to more meaningful work as mentioned above, there is evidence for at least five main benefits.

- Enhanced organizational performance – The very act of shaping one’s own job is beneficial, according to Frese and Fay (2001). Proactive crafting is inherently innovative and creative, and at an organizational level, it’s conducive to flexibility and adaptability. In increasingly dynamic and global business environments, it can contribute to a firm-level competitive advantage.

- Greater engagement – Altering the way we see and engage with our jobs can give us a sense of control over what the tasks do, as well as more fulfillment from the connections we make (Lyon, 2008; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Basically, we have more resources at our disposal, which is intrinsically motivating—it facilitates personal growth and helps us accomplish our goals (Halbesleben, 2010).

- Adding more challenge promotes mastery – When we stretched ourselves a healthy amount through task crafting, we encourage mastery experiences; these, in turn, are conducive to our wellbeing (Gorgievski & Hobfoll, 2008). In job crafting, too, we may seek out feedback and support, potentially boosting our individual job performance (Goodman & Svyantek, 1999)

- It may help us achieve our ‘ideal’ career status – By analyzing our tasks and identifying our goals, we can move toward them in a more effective way through crafting (Strauss et al., 2012). When we add or alter tasks in alignment with our strengths and motives, we experience better person-job fit (Oldham & Hackman, 2010)

- Evidence suggests that it makes us happier – In a study by Slemp and Vella-Broderick (2013), the degree of job crafting that employees got involved with was linked to how well their psychological and subjective wellbeing needs were satisfied.

Are there Drawbacks?

There are, of course, some limitations to job crafting. Organizations are systems, so changing how we view and do things can impact both the firm and the individual—let’s look at some potential downsides.

Drawbacks For Organizations

Misaligned Goals

Essentially, job crafting aims to benefit the employee—it’s neither advantageous nor a pitfall for the company when an employees’ goals are consistent with those of their organization (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001). That alignment is critical in understanding how it plays out in practice, meaning when individual goals and organizational goals are misaligned, we can see negative impacts of job crafting.

In other words, if someone is employed to carry out a certain task, job crafting shouldn’t be a means of changing up the job beyond recognition. It is clearly a pitfall for the organization if a chef creates beautiful cuisine that’s essentially inedible or unsafe. So as Wrzesniewski and Dutton premise, more meaning in one’s role shouldn’t jeopardize organizational effectiveness (2001).

Unequal Access

Another potential disadvantage is more about how we view our jobs in the first instance. In order to job craft, we first need to see our jobs as alterable (Berg, 2013). That is, we may feel certain factors are limiting how free we are to add tasks or alter relationships, for instance, and these can vary based on our roles.

Studies show that senior employees felt they were limited time-wise when it came to crafting, and lower-level employees cited not enough autonomy as an equivalent challenge (Berg et al., 2010). Some workers whose tasks were closely interdependent also felt a similar way, after all, how could they change their roles without disrupting others’ work?

In one respect, this can be seen as a ‘perspective’ or ‘adaptability’ problem, or even suggest more support for the ‘proactive personality’ argument. However, it also raises another issue. That is, some jobs may simply be more ‘craftable’ than others, making some more able to enjoy its benefits. Others, if special steps aren’t taken, may see this as inequity (Schoberova, 2015).

Drawbacks For Individuals

Taking On Too Much

For individuals, it may be tempting to take task crafting a little far. Understandably, if we add on tasks that are overly demanding, or give ourselves excessive tasks while crafting our roles, we risk taking on too much.

If employees aren’t sufficiently informed about the risks of doing so, job crafting can bring with it all the increased dangers of overwork—stress, exhaustion, burnout, and unhappiness (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). In light of this, some authors argue that managers should get more involved in their employees’ job crafting initiatives (Schoberova, 2015).

Exploitation

A final argument against the approach suggests that job crafting leaves some workers open to exploitation. This potentially can occur in the sense that employees might be going ‘above and beyond’ the call of duty without being fairly reimbursed by the organization.

A study of zoo workers by Bunderson and Thompson (2009), for instance, showed some crafters were paid less than their co-workers. This was despite their investing extra time and effort into their newly crafted jobs, in pursuit of deeper meaning at work.

The Job Crafting Questionnaire (PDF)

So, can we measure the extent to which we’re actively job crafting? The Job Crafting Questionnaire (JCQ) has been developed to assess how much we engage in the three different behaviors at work. Designed by positive psychology researchers Stemp and Vella-Brodrick (2013), it is a self-report instrument using a 6-item Likert scale. Based on Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s (2001) 3 areas, the JCQ takes only a short while to complete, with only 15 questions.

With 1 being Hardly Ever, and 6 being Very Often (as often as possible within the organizational context), employees indicate the degree to which they engage in tasks, relationships, and cognitive crafting. Here are some sample items.

Task Crafting Items

Please indicate the extent to which you…

- Give preference to work tasks that suit your skills or interest?

- Introduce new work tasks that you think better suit your skills or interests?

- Change the scope or types of tasks that you complete at work?

Relationship Crafting Items

Please indicate the extent to which you…

- Organize special events in the workplace (e.g., celebrating a co-worker’s birthday)?

- Make friends with people at work who have similar skills or interests?

- Choose to mentor new employees (officially or unofficially)?

Cognitive Crafting Items

Please indicate the extent to which you…

- Remind yourself about the significance your work has for the success of the organization?

- Think about the ways in which your work positively impacts your life?

- Remind yourself of the importance of your work for the broader community?

In developing the JCQ, the authors adapted some items from a measure of job crafting that was designed by Leana et al. (2008) for educators.

Job crafting – the power of personalising our work – Rob Baker

The Job Crafting Intervention

How do we start then, at an organizational level? The good news is that several studies have looked at job crafting interventions, and one, in particular, is described by Van Den Heuvel et al. in their 2015 study. Based on the JD-R Model, the authors developed a one-day training intervention for a Dutch police district to see if job crafting impacted their self-efficacy, wellbeing and positive affect.

The aims were to teach police participants to see their occupational environment and job characteristics under the framework, that is, as resources and demands that they could shape through job crafting (Van Den Heuvel et al., 2015). During the initial day-long session, they also learned to create, establish, and map their own crafting goals on a poster.

In the afternoon they reflected on them, and over the following four weeks, Van Den Heuvel and colleagues followed their progress. They had four key hypotheses, the third of which looked specifically at whether job crafters would experience greater positive affect and lower negative affect than ‘non-crafters’.

Outcomes of the Intervention

This intervention had mixed results. On one hand, there was some support for its efficacy:

- On average, police ‘crafters’ reported having more development opportunities than they did prior;

- Job crafting participants were also found to have higher self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997);

- They reported lower negative affect and an upward in positive affect; and

- Police ‘crafters’ were more inspired to look into and act on their learning opportunities.

On the flip side, the intervention showed no significant effect for reported job crafting behaviors, and the aforementioned ‘upward trend’ in positive affect was statistically insignificant.

The Job Crafting Exercise

Having a good sense of what job crafting involves is an excellent start if you want to give it a try. At the same time, it helps to have an idea of where you might start—what opportunities you might pursue. That’s what The Job Crafting Exercise aims to help you achieve, by encouraging you to view your job as malleable, craftable, and in your control.

In essence, The Job Crafting Exercise helps you perceive seemingly unconnected and segmented tasks as ‘building blocks’ for you to shape in a way that means something.

Developed by Berg, Dutton, and Wrzesniewski (2013), it’s broken into several parts. Throughout all of these, it helps to keep the JD-R Model in mind. Can you identify which aspects are demands, and which are resources? What could you benefit from more of, in terms of reducing your psychological costs—stress, energy, etc.? Where might you welcome a stretch or a challenge?

- First, you’ll create what’s known as a Before Sketch. This helps you understand how you’re allocating and spending your time across various tasks. Think here in terms of energy, and broadly about resources and demands.

- The next step is grouping your whole job into three types of Task Blocks. The biggest of these blocks are for tasks which consume the most of your effort, attention, and time; the smallest blocks are for the least energy-, attention-, and time-intensive tasks, and some will fall into the middle, ‘medium-sized’ blocks.

- With this knowledge of how your personal resources get allocated, you now craft an After Diagram of what your ideal role will look like. Of course, you aren’t stepping completely outside of what you’re formally required to do, but do use your strengths, passions, and motives to create something more meaningful. And in doing so, we use the same idea of task blocks—of course, this time with different priorities.

- Now you have an After Diagram, and you can ‘frame’ different task groups—Role Frames, which you see as serving different functions. Here, you’re crafting your perceptions so you can label different tasks in reimagined ways: rather like our chef-turned-food artisan above.

- The last step is where you create an Action Plan to set out clear goals for the short- and long-term. How are you going to move from your Before Diagram (current job) to your After Diagram (ideal job)?

If you’re looking to access The Job Crafting Exercise, you can purchase the resources at the University of Michigan School of Business (Berg et al., 2013).

The Fatima Job Crafting Case Study

Originally published in the Harvard Business Review, the ‘Fatima’ case study looks in depth at the three different types of job crafting: task, relationship, and cognitive crafting (Wrzesniewski et al., 2010). Here’s a quick overview—at some points, you’ll easily be able to draw parallels with the Job Crafting Exercise described above.

About Fatima

A mid-level marketing manager, Fatima is a high-performing employee who has great relationships with her colleagues and others. While she meets and exceeds the KPIs for her role—monitoring team performance, responding to their inquiries, and so forth, she feels like she’s stuck.

Put simply, Fatima spends a lot more time doing the unengaging, less stimulating parts of her job than the things she’d rather be doing. She’s wondering why she applied for the job in the first place and whether she should get out.

Why Job Crafting?

This ‘stuck’ feeling isn’t only about how Fatima is spending her time. In fact, it’s just as much about how she’s not spending her time. She’s a talented social media user, passionate about learning and wants to integrate that growing expertise into her work for the team. And all the while, Fatima’s driven to improve.

While the case study doesn’t delve much further into her personal feelings, it’s pretty clear that she’s feeling unmotivated. Maybe even like she’s in the wrong job and unsatisfied because of it.

Task Analysis and Job Crafting

The great thing about Wrzesniewski and colleagues’ (2010) Fatima Case Study is that it offers visuals that clearly link task analysis with job crafting. Below, a diagram—similar to the cook/food artisan figure we saw earlier—shows how Fatima’s new tasks look before and after she’s reshaped and reimagined it.

Fatima’s role before crafting:

Here, we see task analysis coming into play; Fatima’s systematic approach to visualizing what she does and how much time she devotes to different aspects of her marketing role. A considerable bulk of her time is spent problem-solving with her team and responding to their questions, as one example. Tasks that she’s passionate about—like strategizing—fall toward the bottom, where she spends the least of her time.

Source: Wrzesniewski et al. (2010)

Fatima’s role after crafting:

Now, Fatima’s started from a different place: from her passions, motives, and strengths. As you’ll recall, she’s a social media enthusiast and wants to craft relevant tasks into her role. In fact, while she’s still performing the same job, she’s expanded it to encompass two roles.

Empowering her team covers a lot of the same duties, but from a new perspective that frames her input as valuable in terms of the organization’s goals. Simultaneously, outside the grey box, she’s added Building and using social media tasks that mean something to both her and the firm.

Source: Wrzesniewski et al. (2010)

If you’re after more information, as well as another related example, you can find the whole job crafting case study here.

Job Crafting Workshops

The Job Crafting Exercise can be done in workshops as groups. Typically they don’t need to last longer than a couple of hours as you work through the stages described above. It’s an interesting and often very useful way to get managers involved, as suggested earlier.

This detailed example will show you what a Job Crafting Workshop looks like in practice (Berg et al., 2013).

Books on the Topic

You can get the whole Job Crafting Exercise book from the Center for Positive Organizations, but you will find that most information you need is readily available online.

Jump ahead to the reference section of this article if you’re after the most important research papers to date.

3 Recommended Videos

These three videos are quick takes on job crafting, with Prof Amy Wrzesniewski in the lead with the amazing work she has been doing.

1. Job Crafting – Amy Wrzesniewski on creating meaning in your own work

Professor Amy Wrzesniewski gives a little overview of her original hospital cleaning crew study, and how this gave rise to the idea of job crafting.

2. Redesigning Wellness Podcast 089: Job Crafting and Finding the Meaning of Work with Amy Wrzesniewski

Here’s another interview with Professor Wrzesniewski and Jen Arnold. Among other things, they discuss its role in performance, its limits, and how job crafting can redefine wellness in organizations.

3. Job Crafting: A Fresh Take on Your Old Job

Here’s a little overview of job crafting that appeared on TV. In this summary, there is a little discussion on how you can get started, and the potential downsides of crafting your job. Also, some useful tips for bringing up the topic with your boss.

A Take-Home Message

The idea that your calling isn’t always “somewhere out there” doesn’t have to be terrifying. Especially if that’s because you’ve already got knowledge and tools to craft your own meaning. After all, as it’s been argued before, all employees are potential job crafters, and that alone is an empowering piece of knowledge.

Have you used job crafting to turn around a dull job? Or have you implemented a job crafting intervention before?

Why not share your thoughts on job crafting with us, I’d love to hear them!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free.

- Bakker, A.B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T., Schaufeli, W.B. & Schreurs, P. (2003). A multi-group analysis of the Job Demands-Resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10, 16–38.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan.

- Berg, J.M., Dutton, J.E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2007). What is Job Crafting and Why Does It Matter?. Retrieved from https://positiveorgs.bus.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/What-is-Job-Crafting-and-Why-Does-it-Matter1.pdf

- Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2-3), 158‐186.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. Purpose and meaning in the workplace, 81, 104.

- Bunderson, J. S., & Thompson, J. A. (2009). The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(1), 32‐57.

- Caldwell, D. F., & O’Reilly, C. A., III. (1990). Measuring person-job fit with a profile-comparison process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 648–657.

- Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli, & Hetland, 2012 Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 1120–1141.

- Dubbelt, L., Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2019). The value of job crafting for work engagement, task performance, and career satisfaction: longitudinal and quasi-experimental evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 300-314.

- Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. In B. M. Staw & R. I. Sutton (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior(Vol. 23, pp. 133-187). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science

- Garg, P., & Rastogi, R. (2006). New model of job design: motivating employees’ performance. Journal of Management Development, 25(6), 572-587.

- Goodman, S. A., & Svyantek, D. J. (1999). Person-organization fit and contextual performance: Do shared values matter? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 254–275.

- Gorgievski, M. J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2008). Work can burn us out or fire us up: Conservation of resources in burnout and engagement. In J. R. B. Halbesleben (Ed.), Handbook of stress and burnout in health care (pp. 7–22). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

- Hackman, J. R.& Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250-279.

- Hackman, J. R.& Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Harquail, C.V. (2009). A Job Crafting Example: The Pink Glove Dance, Retrieved from http://authenticorganizations.com/harquail/2009/12/08/a-job-crafting-example-the-pink-glove-dance/

- Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1169-1192.

- Makul, A. Z. A., Rayhan, S. J., Hoque, F., & Islam, F. (2013). Job characteristics model of Hackman and Oldhamin garment sector in Bangladesh: A case study at Savar 109 area in Dhaka district. International Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 1(4), 188-195.

- Mindtools.com. Job Demands-Resources Model. Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/media/Diagrams/jdr-model-new.jpg

- Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (2010). Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 463–479.

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in organizational behavior, 30, 91-127.

- Schoberova, M. (2015). Job crafting and personal development in the workplace: Employees and managers co-creating meaningful and productive work in personal development discussions. MAPP Capstone Project, University of Pennsylvania.

- Seligman, M. E. (2004). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon and Schuster.

- Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). The Job Crafting Questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2), 126-146.

- Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 580–598.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. South-African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36, 1–9.

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of occupational health psychology, 18(2), 230.

- Van den Heuvel, M., Demerouti, E., & Peeters, M. C. (2015). The job crafting intervention: Effects on job resources, self-efficacy, and affective wellbeing. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 511-532.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of management review, 26(2), 179-201.

- Wrzesniewski, A., Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Managing yourself: Turn the job you have into the job you want. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 114-117.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

This is great! If implemented correctly should improve the employees experience and also the engagement. This approach values the person and makes the job meaningful.

Fantastic article! Job crafting is an essential aspect of career development, and your insightful post provides a clear understanding of its significance. The five examples and exercises you’ve shared offer practical ways for individuals to shape their roles and find fulfillment in their careers. For those seeking ‘IT Jobs for Freshers,’ this knowledge can be invaluable in creating a more rewarding and tailored work experience. Thanks for shedding light on this empowering concept

I found this article fascinating, informative and logical as it separated technical, emotional and intellectual issues on job redesign and recrafting. Also it gave agency to the individual incumbent if the job instead of doing something to them! I worked as an Organisation Consultant in the 90 s and then VP of HR & OD and wish I had broken down the concepts and brought it in organisationally. I had already studied and written college papers on job redesign in the 1980s and in the 90 s and this century studied psychotherapy which melds with the thoughts and concepts in this article. Well done all