What Is Self-Leadership? Models, Theory, and Examples

We are not born with an instruction booklet, but if we were, I am sure the first chapter would explain the art of self-leadership.

We are not born with an instruction booklet, but if we were, I am sure the first chapter would explain the art of self-leadership.

The fact is, we all lead ourselves to some extent. How efficiently we do that determines how much we live life with purpose and intent. Yet, despite its central importance to leading a meaningful life, it seems that the term self-leadership often warrants explanation and doesn’t form part of our common vocabulary.

This article offers a basic overview of what self-leadership is and its scientific foundations.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Leadership Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or others adopt positive leadership practices and help organizations thrive.

This Article Contains:

Self-Leadership Explained

Self-leadership is the practice of understanding who you are, identifying your desired experiences, and intentionally guiding yourself toward them. It spans the determination of what we do, why we do it, and how we do it.

The term ‘self-leadership’ first emerged from organizational management literature by Charles C. Manz (1983), who later defined it as a “comprehensive self-influence perspective that concerns leading oneself toward performance of naturally motivating tasks as well as managing oneself to do work that must be done but is not naturally motivating” (Manz, 1986).

The concept was based on the (then novel) insight that self-leadership is a prerequisite for effective and authentic team leadership (Manz & Sims, 1991). In fact, more autonomous, self-leading workers are more productive, irrespective of their work role (Birdi et al., 2008).

Since its first mention, discussion and examination of the self-leadership concept remained predominantly in organizational leadership and management contexts. More recently, Marieta Du Plessis (2019) acknowledged the opportunity to complement the concept with insights from positive psychology research, offering the following definition:

Positive self-leadership refers to the capacity to identify and apply one’s signature strengths to initiate, maintain, or sustain self-influencing behaviors.

Du Plessis emphasizes the importance of value-based self-inspiration and self-goal setting in the self-leadership journey.

When considering this definition, the broader applicability of self-leadership becomes evident. In fact, the concept of self-leadership draws on several interdisciplinary theoretical models and frameworks, including many from the field of positive psychology.

Theories and Models of Self-Leadership

Theoretical foundations

Self-control is synonymous with self-management and self-regulation and describes the iterative process of determining a desired end state, comparing that to the current state, and subsequently taking action to close the gap between the two (Carver & Scheier, 1981).

It is important to note that especially in the early literature, the terms self-leadership and self-management were often used interchangeably.

However, self-management is a necessary but not entirely encompassing element of self-leadership in that it simply refers to the internally regulated management and execution of tasks (i.e., addressing the how of an action). In this case, the choice of the task itself and the underlying reason for the choice are externally regulated.

In contrast, self-leadership includes an internally regulated choice, value alignment, and execution of the chosen activity (i.e., addressing the what, why, and how).

Social-cognitive theory acknowledges the triadic interaction between our thoughts, behavior, and socio-political environment (Bandura, 1986).

Self-determination theory describes the reciprocity between human motivation and a purposeful life. It highlights the role of internally regulated and intrinsic motivation as a driver behind self-leadership behaviors (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

However, self-leadership theory is also well suited to a couple of other theories. In light of the central notion of self-determined action in line with one’s intrinsic needs, in particular self-actualizing behaviors, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is one such view.

Furthermore, self-leadership is rooted in self-awareness in combination with self-management, which, according to Daniel Goleman (2005), form two of the four pillars of emotional intelligence.

Self-leadership models

There is still a general lack of self-leadership models and guiding frameworks in line with the relative infancy and historical development of the scientific self-leadership evidence base.

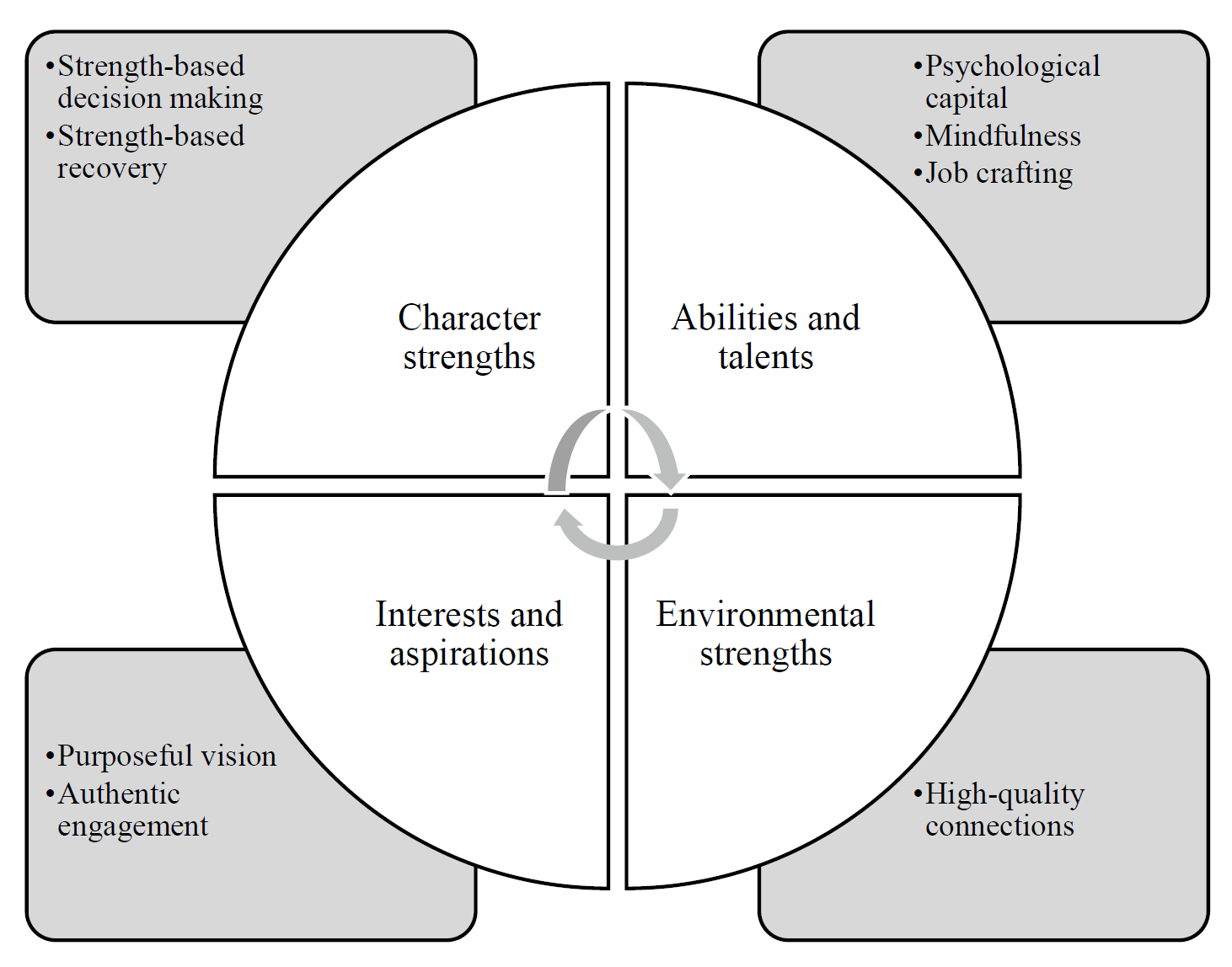

The positive self-leadership capability model explicitly combines insights from the organizational leadership literature with those from organizational and positive psychology (Du Plessis, 2019).

This model is based on the strengths-based capability framework (Stander & Van Zyl, 2019). It is aligned with experiences from delivering organizational interventions regarding positive self-leadership development.

It offers several competencies (outer quadrants) across four dynamically interacting core capabilities (inner quadrants): character strengths, abilities and talents, interests and aspirations, and environmental strengths (Du Plessis, 2019).

The positive self-leadership capability model (reprinted with permission from Du Plessis, 2019)

While most of these capabilities draw on popular, well-known concepts from positive psychology research, environmental strengths refer to an individual’s ability to draw on resources from their socio-political and built environment.

8 Core Competencies and Skills

Given the broad field of self-leadership and lack of comprehensive and empirically tested self-leadership models to date, it might be more helpful to focus on the various competencies involved in it.

Here are some cognitive and behavioral strategies that effective self-leadership draws on.

1. Self-awareness and self-knowledge

Self-awareness is the ability to perceive yourself clearly through inward inspection. It is the act of practicing mindfulness, with the attention directed toward yourself.

Self-awareness allows us to perceive our current inner reality or state and, as such, is a prerequisite of self-control and self-regulation (Carver & Scheier, 1981; Silvia & O’Brien, 2004).

Basic self-knowledge is vital to understanding one’s needs, motives, and drives. At a minimum, this includes the following four elements:

Personality traits

Our personality traits predict and explain our thoughts, feelings, and behavior, in particular spontaneous action. Interestingly, individuals with a higher conscientiousness score (one of the Big Five character traits) have been shown to be more efficient self-leaders (Stewart, Carson, & Cardy, 1996).

Individuals with a lower conscientiousness score and the ambition to improve their self-leadership skills could place particular effort on cultivating conscientiousness.

Personal strengths and weaknesses

These provide insight into what we feel drawn toward, how we can conquer problems and perform exceptionally well, what drains us, and where we tend to procrastinate.

Values

Our values are what is most important to us in life, and, knowingly or not, we make decisions based on them. They are the reason why we do what we do.

Talents and interests

Our talents and interests offer insight into how we can put our strengths to work, enjoy the process, and maximize our chances of succeeding and serving a purpose bigger than ourselves.

Self-knowledge allows us to answer questions such as ‘What am I feeling and why?’; ‘What is important to me?’; ‘How can I succeed and when do I need to be particularly vigilant on my goal journey?’; and ‘What is my sense of purpose?’

2. Identifying desired experiences

Arguably, we all strive for happiness, and our goals are a means to achieve that. However, research shows that our ability to predict what will make us happy is poorer than we think (Gilbert & Wilson, 2006). So it is important to understand insights from happiness research as well as how to align our goals or desired experiences with our values.

This way, we will be more motivated to pursue our goals, and, once we have attained them, they will be the means to happiness we were hoping for in the first place. This competency also includes identifying opportunities to live in line with one’s values across the various life domains.

3. Constructive thought and decision making

As humans, we like to think of ourselves as a cognitive and rational species that makes thoughtful choices along the path of life. Unfortunately, many of the processes happening inside our minds are anything but rational (Kahneman, 2012).

An example of this is the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957). Another is that our ability to reason is inhibited when we feel stressed and are experiencing the so-called fight-or-flight response (also known as the amygdala hijack).

Unfortunately, we are somewhat neurologically wired to perceive threats and therefore have to proactively practice positivity if we want to use our full potential to make rational decisions (Fredrickson, 2001). When we are relaxed and in a positive emotional state, we can think creatively and innovatively (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005).

Finally, this includes developing a growth mindset – the belief in our ability to develop and change things or ourselves (Dweck, 2016). This implies an understanding that while we cannot control all of our experiences, we can control how we choose to react to them.

Therefore, understanding the fundamentals of constructive thought and decision-making processes, plus practicing mindfulness and positivity to cultivate them, are essential elements of self-leadership.

4. Planning and goal setting

The planning and goal-setting competencies include breaking bigger dreams into manageable milestones and then optimizing each milestone into a goal.

The goal-setting process includes articulating SMART goals, identifying contingency plans, proactively committing by documenting it all, and establishing accountability and using positive reward upon goal attainment.

5. Optimizing motivation

Optimizing motivation includes the competency of adjusting one’s goal to become more appealing. This can be achieved by identifying an intrinsically motivating goal behavior and aligning the goal to one’s values and self-concept (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Optimizing motivation also means understanding the role of willpower, a finite resource but one that can be cultivated. Finally, this competency includes an awareness that we may not feel ready or confident when trying a new goal behavior. Instead, self-efficacy is developed by taking small, continuous steps toward the goal (Bandura, 1977).

6. Harnessing the ecosystem

The nature versus nurture debate is an ongoing point of curiosity regarding the magnitude of influence the environment versus our genetics have on our behavior. Do we mostly learn our behavior through our life circumstances, experiences, and the people around us? Or is it innate and mostly inherited?

These days, scientists agree that the answer isn’t usually found at either extreme end of the scale. Instead, we know that they usually both interact and together influence the way we act.

Harnessing the ecosystem is about proactively seeking support for our goal behavior in the social, organizational, community, political, and physical environment we live in. This includes mobilizing social support, cueing new goal behavior through small tweaks in our physical environment, and identifying goal-aligned resources in our community.

7. Amplifying performance

There are three techniques worth learning to amplify self-leadership performance:

- High-performance planning entails asking yourself a set of questions about how you can perform optimally during a predefined period and reviewing your ambitions at the end of it. As such, it is a particular form of planning, goal setting, and intention forming.

- Self-coaching is a constructive thought strategy and involves solution seeking by mentally navigating a coaching framework, such as the GROW model.

- Functional visualization techniques (also referred to as functional imagery training) involve detailed mental rehearsal of the desired goal behavior, which has been shown to significantly increase the likelihood of goal attainment (Solbrig et al., 2018).

8. Embracing failure and cultivating grit

Tal Ben-Shahar famously said:

Learn to fail or fail to learn.

(Ben-Shahar, 2014)

Most people will fail at some stage on the path to their goals. Often when people don’t stick to their plans, they get so frustrated with themselves in those situations that they avoid thinking about the whole topic altogether (cognitive dissonance at its best).

They give up because they will not attain the goal as quickly or to the extent that they had planned and therefore feel like a smaller win is not worthy. Both are fatal to our goal attainment.

It is important to adjust one’s expectations about encountering some form of failure along the goal path. Other important competencies to cultivate are self-compassion and grit.

Self-compassion is treating yourself with the same care, love, and respect you would give to a struggling close friend. Research shows that contrary to the popular belief that self-compassion leads to complacency, it actually increases motivation (Neff, 2003).

Grit is a combination of passion and perseverance for long-term goals (Duckworth & Gross, 2014). Grit is what can, more reliably than any other characteristic, distinguish the successful from the non-successful.

You can cultivate it by putting deliberate effort into developing your talents into skills; and, when you take your skill and put effort into refining it, you will accomplish achievement.

A Real-Life Example

However, when reflecting on the practice of leading oneself intrinsically, proactively, and regardless of external circumstance, one person comes to mind immediately: Viktor Frankl.

As described in his (1984) book Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl famously survived the Holocaust and three years of incarceration in Nazi concentration camps. Despite the immense hardships he experienced there, Frankl was able to survive.

Moreover, he demonstrated many critical self-leadership skills throughout his experience. He had a profound understanding that he could not change what was happening to him and his fellow inmates, but he could choose how to respond to it.

He understood the importance of values in life, had a strong awareness of his own, and lived by them, and in doing so, he found meaning and purpose. He exhibited constructive thought strategies and continuously identified opportunities to contribute to the wellbeing of his inmates. And, he managed to persevere in this way not only throughout the entire period of incarceration but also afterward.

Great leadership starts with self-leadership – Lars Sudmann

Training in Self-Leadership: 6 Courses and Programs

Due to the infancy of the self-leadership field, courses and programs are still somewhat rare. It should also be noted that the course information provided online is often brief and vague, which makes it hard to judge how many self-leadership competencies are covered.

Most of the current courses are positioned in the organizational leadership training arena. Here are a few courses worth mentioning:

- The Ken Blanchard® Companies provide worldwide in-person and online training (or a combination thereof), explicitly for employees.

- Mainstream Corporate Training offers self-paced self-leadership online training and live online training.

- Ducidium Pty Ltd provides in-person training in Australia and is currently developing self-paced virtual training.

Regarding training for self-leadership more broadly (i.e., not tied to the workplace), the following courses can be recommended:

- Stanford Graduate School of Business offers a free online course developed by lecturer Ed Batista called ‘The Art of Self-Coaching.’ While Batista refers to self-coaching rather than self-leadership, he covers many critical self-leadership skills topics and competencies. The easiest way to access the course may be via Batista’s website, where he also offers a course outline.

- Self Leaders is a Stockholm-based company offering virtual, experience-based, and customized self-leadership training worldwide. They also frequently offer free short workshops and events.

- Dr. Maike Neuhaus offers a comprehensive online self-leadership course called Fresh Start, which gives you clarity on change, and helps you flourish.

8 Inspiring Quotes

Mastering others is strength. Mastering yourself is true power.

Lao Tze

Self-leadership… is about influencing ourselves, creating the self-motivation and self-direction we need to accomplish what we want to accomplish.

Charles C. Manz

All human beings are self-leaders; however, not all self-leaders are effective at self-leading.

Charles C. Manz

Being a self-leader is to serve as chief, captain, president, or CEO of one’s own life.

Peter Drucker

The first and best victory is to conquer self.

Plato

The one thing you can’t take away from me is the way I choose to respond to what you do to me.

Viktor E. Frankl

First, be a leader of yourself. Only then can you grow to lead others.

David Taylor-Klaus

Leadership’s First Commandment: Know Thyself… No tool can help a leader who lacks self-knowledge.

Harvard Business Review editorial

PositivePsychology.com’s Resources

The following articles will make great supplemental reading:

- How to Improve Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace

- Self-Therapy for Anxiety and Depression

- Positive Leadership: 30 Must-Have Traits and Skills

- What’s Your Coaching Approach? 10 Different Coaching Styles Explained

Two special masterclasses can be particularly helpful as additional resources and are highly recommended:

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop positive leadership skills, this collection contains 17 validated positive leadership exercises. Use them to equip leaders with the skills needed to cultivate a culture of positivity and resilience.

A Take-Home Message

A relatively new concept, self-leadership warrants more research. In particular, the current evidence base around self-leadership will benefit significantly from an interdisciplinary examination by complementing organizational leadership literature with insights from positive psychology.

Also, self-leadership competencies are now increasingly receiving attention from education professionals, who are stressing the importance of adapting school curricula to the rapidly changing workforce landscape due to advances in technology.

Here, it is highlighted that graduates need to be self-aware, self-driven, flexible, and adaptable to an ever-changing work environment (Freeman, 2020).

Now dubbed as a key 21st-century skill, learning the art of self-leadership will indeed form part of a fundamental life instruction booklet, maybe sooner rather than later.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Leadership Exercises for free.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Ben-Shahar, T. (2014). Choose the life you want: The mindful way to happiness. The Experiment.

- Birdi, K., Clegg, C., Patterson, M., Robinson, A., Stride, C. B., Wall, T. D., & Wood, S. J. (2008). The impact of human resource and operational management practices on company productivity: A longitudinal study. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 467–501.

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and self-regulation. Springer.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (1st ed.). Springer.

- Du Plessis, M. (2019). Positive self-leadership: A framework for professional leadership development. In L. E. Van Zyl & S. Rothman, Sr. (Eds.), Theoretical approaches to multi-cultural positive psychological interventions (p. 450). Springer International Publishing.

- Duckworth, A., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control and grit. Current Directions in Psychological Science: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 23(5), 319–325.

- Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: The new psychology of success (updated ed.). Ballantine Books.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning (rev. ed.). Washington Square Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. The American Psychologist, 60(7), 678–686.

- Freeman, O. A. M. (2020). Future trends in education. In W. Leal Filho, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, P. G. Özuyar, & T. Wall (Eds.), Quality education (pp. 337–351). Springer International Publishing.

- Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2006). Miswanting: Some problems in the forecasting of future affective states. In S. Lichtenstein & P. Slovic (Eds.), The construction of preference (pp. 550–564). Cambridge University Press.

- Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional intelligence (10th Anniversary ed.). Bantam Books.

- Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin.

- Manz, C. C. (1983). Improving performance through self-leadership. National Productivity Review, 2(3), 288–297.

- Manz, C. C. (1986). Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory of self-influence processes in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 589.

- Manz, C. C., & Sims, H. P. (1991). SuperLeadership: Beyond the myth of heroic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 19(4), 18–35.

- Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

- Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 333–335.

- Silvia, P. J., & O’Brien, M. E. (2004). Self-awareness and constructive functioning: Revisiting “the human dilemma.” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 475–489.

- Solbrig, L., Whalley, B., Kavanagh, D. J., May, J., Parkin, T., Jones, R., & Andrade, J. (2018). Functional imagery training versus motivational interviewing for weight loss: A randomised controlled trial of brief individual interventions for overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 43(4), 883–894.

- Stander, F. W., & Van Zyl, L. E. (2019). The talent development centre as an integrated positive psychological leadership development and talent analytics framework. In L. E. Van Zyl & S. Rothmann, Sr. (Eds.) Positive psychological intervention design and protocols for multi-cultural contexts (pp. 33–56). Springer International Publishing.

- Stewart, G. L., Carson, K. P., & Cardy, R. L. (1996). The joint effects of conscientiousness and self-leadership training on employee self-directed behavior in a service setting. Personnel Psychology, 49(1), 143–164.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

It is insightful powerful reading