Resilience Examples: What Key Skills Make You Resilient?

Mental health encompasses far more than the mere absence of disorders.

Mental health encompasses far more than the mere absence of disorders.

There are a number of dimensions when it comes to positive mental health, one of which is resilience.

Resilience is the process of being able to adapt well and bounce back quickly in times of stress. This stress may manifest as family or relationship problems, serious health problems, problems in the workplace or even financial problems to name a few.

Developing resilience can help you cope adaptively and bounce back after changes, challenges, setbacks, disappointments, and failures.

Research has shown that resiliency is pretty common. People tend to demonstrate resilience more often than you think. One example of resilience is the response of many Americans after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and individuals’ efforts to rebuild their lives.

Demonstrating resiliency doesn’t necessarily mean that you have not suffered difficulty or distress. It also doesn’t mean you have not experienced emotional pain or sadness. The road to resilience is often paved with emotional stress and strain.

The good news is resilience can be learned. It involves developing thoughts, behaviors, and actions that allow you to recover from traumatic or stressful events in life.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Resilience Exercises for free. These engaging, science-based exercises will help you to effectively deal with difficult circumstances and give you the tools to improve the resilience of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- A Definition of the Resilient Person

- Traits, Qualities, and Characteristics of the Resilient Person

- The Main Factors Contributing to Resilience

- Is Resilience a Skill or Character Strength?

- Resilience Skills and How to Train Them

- Resilience Strategies for Coping and Bouncing Back Stronger

- Different Types of Resilience

- What are the Key Components and Elements of the Resilient Life?

- An Example of Resilient Behavior

- A Take-Home Message

- References

A Definition of the Resilient Person

There is an evolving definition when it comes to resilience. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) resilience is defined as the process of adapting well in the face of trauma or tragedy, threats or other significant sources of stress (Southwick et al., 2014)

When it comes down to it, the concept of resilience is a complex one. In reality, resilience is more likely to exist on a continuum that may present itself in differing degrees across multiple domains of life. (Southwick et al., 2014)

For example, someone may be very resilient in the workplace but not as resilient in his or her personal life and personal relationships. In other words, the idea of resilience is relative and depends upon the situation.

Resilience may also change over time depending on your interactions and the environment around you. The more that is learned about resilience, the more potential there is for integrating these concepts into relevant areas of life.

This integration is beginning to foster an important shift in thinking. Clinicians and researchers are starting to sense the importance of focusing on evaluating and teaching methods to enhance resilience rather than continually focusing on or examining the negative consequences of trauma or stress.

This is an important shift to pay attention to because it signifies a move away from a purely deficit-based model of mental health toward inclusion of strength and competency-based models. This allows greater focus on prevention and building strengths in addition to addressing psychopathology. (Southwick et al, 2014)

Developing skills of resilience can help you face challenges and difficulties in life, which can help you feel better and cope better.

In essence, resilience helps you handle stress more positively. Everything in life is about balance. Without the darkness, you would not appreciate the light. Without sadness, you would not appreciate joy. Like the yin and the yang, you need both positive and negative emotions and experiences to appreciate what you have.

Life isn’t always going to be easy – but it shouldn’t always be hard. Whatever you resist persists, so learning how to let go and adapt to change and adversity can really help you move into a new mindset, and develop more resilience along the way.

It’s natural to have a tendency to try and control things. There are things you can control in life but there are also things you cannot.

Developing resilience is a very personal process. Each of us reacts differently to stress and to trauma. Some people bounce back quickly while others tend to take longer. There is no magic formula.

What works well for one person may not necessarily work for another, which is one of the biggest reasons to learn multiple techniques for enhancing resilience.

Traits, Qualities, and Characteristics of the Resilient Person

According to Conner and Davidson (2003), resilient people have certain characteristics. These characteristics may include:

- Viewing change as a challenge or opportunity

- Commitment

- Recognition of limits to control

- Engaging the support of others

- Close, secure attachment to others

- Personal or collective goals

- Self-efficacy

- Strengthening effect of stress

- Past successes

- Realistic sense of control/having choices

- Sense of humor

- Action-oriented approach

- Patience

- Tolerance of negative affect

- Adaptability to change

- Optimism

- Faith

Conner and Davidson also developed the Conner-Davidson Resilience scale (CD-RISC), which is comprised of 25 items, each rated on a 5-point scale from 0-4 with higher scores that reflect a greater sense of resilience.

The scale was administered to general psychiatric outpatients, a clinical trial of generalized anxiety disorders, two clinical trials of PTSD and community samples.

The Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale

- Able to adapt to change.

- Close and secure relationships.

- Sometimes fate or God can help.

- Can deal with whatever comes.

- Past success gives confidence for new challenge.

- See the humorous side of things.

- Coping with stress strengthens.

- Tend to bounce back after illness or hardship.

- Things happen for a reason.

- Best effort no matter what.

- You can achieve your goals.

- When things look hopeless, you don’t give up.

- Know where to turn for help.

- Under pressure, focus and think clearly.

- Prefer to take the lead in problem-solving.

- Not easily discouraged by failure.

- Think of self as a strong person.

- Make unpopular or difficult decisions.

- Can handle unpleasant feelings.

- Have to act on a hunch.

- Strong sense of purpose.

- In control of your life.

- You like challenges.

- You work to attain your goals.

- Pride in your achievements.

By using this scale, the study concluded that resilience is quantifiable and influenced by health status, is modifiable, and can improve with treatment. Individuals with mental illness, for example, tend to have lower levels of resilience when compared with the general population.

Greater improvement of resilience also corresponds to higher levels of global improvement. The study also surmised that it is possible to perform well in one area such as work, in the face of adversity, but function poorly in another area, such as personal relationships.

Moreover, the study surmised that resilience may either be a determinant of response or an effect of exposure to stress. Further studies would be required to inform whether resilience predated exposure to trauma, protected against post-trauma or if through certain circumstances survivors developed further resilience after traumas occurred.

The Main Factors Contributing to Resilience

There are many ways to increase resilience. Some of those include having a good support system, maintaining positive relationships, having a good self-image and having a positive attitude.

Other factors that contribute to resiliency include:

- Having the capacity to make realistic plans.

- Being able to carry out those plans.

- Being able to effectively manage your feelings and impulses in a healthy manner.

- Having good communication skills.

- Having confidence in your strengths and abilities.

- Having good problem-solving skills.

Developing resiliency can help you maintain caring relationships with others and help you maintain a positive and easygoing disposition. It can also help you develop good coping skills and improve cognitive thinking skills.

Those who develop resilience tend to cope much better with life than those who aren’t resilient and they may even be happier.

Some people are naturally more resilient, however, you can work to enhance your level of resilience. You can learn how to bounce back from adversity in a healthy manner.

In the end, resilience is a skill that can be cultivated and nurtured.

Is Resilience a Skill or Character Strength?

Clinical psychologist Christina G. Hibbert, Psy. D. defines resilience as the ability to bounce back after life tears you down.

Those who are more resilient have learned to move past obstacles and challenges in a healthy way.

Resilient people learn and know how to weather the storms of life that come along. They have also learned how to set themselves back on even ground after a stressful event.

Joyce Marter, LCPC, a therapist and owner of a counseling practice, describes resilience as the strength to continue on the path that you know to be true, despite challenges and obstacles (Marter, 2019).

Your level of resilience determines how quickly you get back up when the air gets knocked out of you. It helps you push through life’s circumstances and meet challenges head-on.

Resilience has even been compared to learning how to play the guitar. When you first try to play, your fingers get sore and you get frustrated. Some may even quit after the second or third lesson.

A resilient person pushes past that initial discomfort and soon begins to realize that there are greater joy and satisfaction ahead.

As part of this process, your fingers get tougher and stronger the more you practice. Pretty soon the process becomes effortless and even enjoyable.

In essence, your fingers become more resilient the more you practice. The more you play, the more your fingers are able to tolerate the string tension, and the strength required to play well.

Learning to play the guitar is a great metaphor for resilience. What it tells us is that resilience is a character trait and a strength that can be learned.

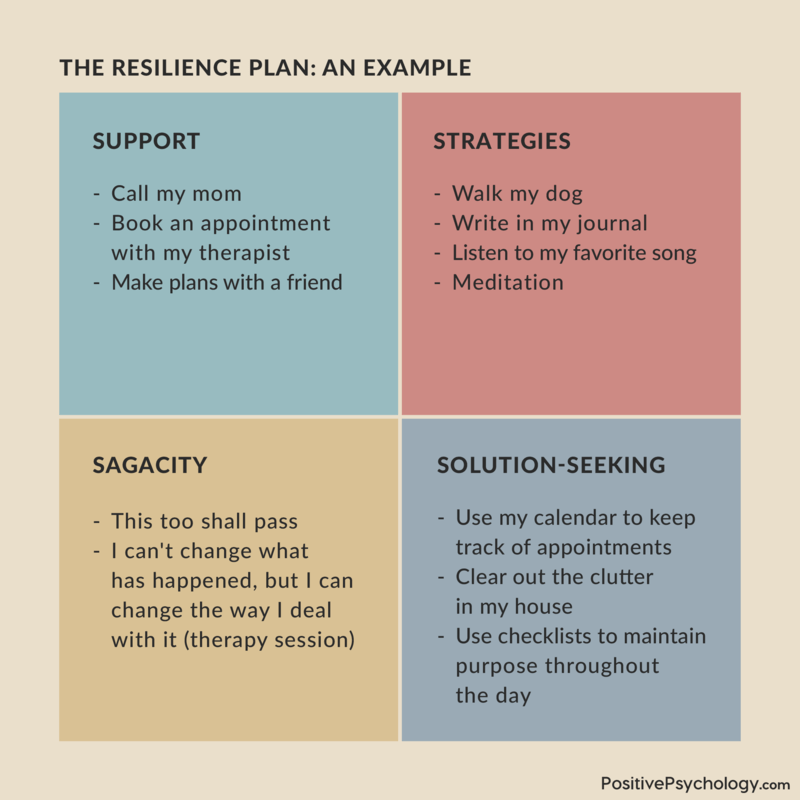

The Four S’ of Resilience is a tool that allows individuals to draw on resilience sources they have used in the past and create a plan for tackling adversity in the future.

There are two parts to the plan.

In Part A, the individual reflects on a past difficulty they overcame and identifies the Four S’ (supports, strategies, sagacity, and solution-seeking) they drew on at that time.

Part B uses those responses to create a plan of resilience for any present or future difficulties.

The beauty of this tool is that the resources identified will always be relevant to the individual, no matter how ridiculous they may seem to another person. If an individual finds comfort in listening to the same pop song on repeat, they can include that in their resilience plan, knowing it will help them. In this way, these resilience plans are highly individualized and thus personally meaningful and useful.

Resilience Skills and How to Train Them

Sydney Ey, Ph.D. an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University has developed a Resilience Building webinar. Viewers will come to recognize what builds and what depletes resilience.

Going through the below exercise can help you create a plan for managing resilience and help you learn more about yourself in terms of your strengths and weaknesses.

Resilience Building Plan Worksheet

- Recognize Your Signs of Stress.

- Where do you feel stress in your body?

- What are some of the bad habits you engage in when feeling stressed?

- Focus on Building Physical Hardiness.

- What kind of small changes can you invest in to improve your health? (Better sleep, better nutrition, hydration, exercise, etc.)

- List one small change you can make now.

- Strengthen the Relaxation Response – Calm Body and Calm Mind.

- List some activities at home that could help you relax.

- List some activities at work that could help you relax.

- Try out some new relaxation skills such as mindfulness or meditation apps such as Calm or Headspace.

- Try some self-soothing activities such as:

- Tactile (Holding something comforting or soothing)

- Smell (Smell of lavender, fresh air)

- Visual (Puppy or kitten photos, looking out the window, etc.)

- Auditory (Listen to music, listen to sounds of nature)

- Taste (Drinking some tea, eating chocolate)

- Identify and Use Your Strengths.

- Describe a time when you were able to overcome or handle a major challenge in life.

- What did you learn about yourself?

- What personal strengths did you draw upon?

- Draw upon an image of when you were the most resilient.

- How might you apply this strength now?

- Increase Positive Emotions on a Daily Basis.

- Identify sources of humor or joy.

- Express gratitude, visit someone or write a letter.

- List your accomplishments.

- Engage in Meaningful Activities.

- Notice what happened in your day that was meaningful on a regular basis.

- What kinds of activities did you find meaningful?

- Identify activities that put you in the flow. (Enjoyable things you do that cause you to lose track of time.)

- Counter Unhelpful Thinking.

- Write down what you are thinking about when you get stressed and then ask: What is the worst that can happen and could I survive it? What is the best that could happen? What would I tell a friend in a similar situation?

- If you can’t stop thinking about something, write about it a couple of times over a 4-week period for about 15 minutes each time. Notice how your story changes or your perspective becomes clearer each time.

- If you are being hard on yourself, practice self-compassion and learn to be kind to yourself. Give yourself a mental break or a pat on the back.

- Remember a hero, a coach or a mentor that encouraged you when you doubted yourself.

- Create a Caring Community.

- Connect with friends and family on a regular basis.

- Identify your sources of support.

- Work

- At home.

- In the community.

- Practice good communication and conflict resolution skills.

Another great option for building resilience is the 4-factor approach created by Deborah Serani, Psy. D. The 4-factor approach is a great option for helping clients better understand the concept of resilience. Serani, a clinical psychologist, uses this approach with her clients (Serani, 2011).

The 4-factor Approach

- Stating the facts.

- Placing blame where it belongs.

- Reframing.

- Giving yourself time.

This unique approach can help you learn how to develop skills of resilience. Serani uses the idea of a bad car crash as a tool for building resilience.

Let’s assume you crashed your car and have some injuries. As a result of this, you may even need to miss work for a few days in order to heal.

The first step involves simply listing or talking about the trauma without magnifying it. For example, you might say to yourself, “I wrecked my car and I got hurt. However, I was able to call for help and get myself patched up and get the car fixed.”

The second step involves taking ownership, but not beating yourself up. Instead of blaming yourself, you could simply say: “OK, I wrecked my car. It happens. It was dark and it was an accident. I’m OK.”

The third step involves reframing and re-evaluating the event in your mind. This might also be known as looking for the silver lining. Things could have been worse. You could have been seriously injured or hurt someone else. Reframing involves looking for the bright side of the situation and finding something to be grateful for.

Finally, the last step involves giving yourself some time to heal and adjust after the trauma.

Engaging in this simple process can go a long way to helping you heal and feel more resilient.

By going through this 4-step process, you can train your brain and your mind to think differently. You can learn to look at situations differently and find that silver lining. The more you engage in this process, the more resilient you will be overall.

The Realizing Resilience Masterclass

The Realizing Resilience course does so much more than just teach you the six pillars of mastering resilience. It also equips you to help others deal with the challenges in life.

This highly acclaimed masterclass provides you with ample tools and materials to apply the science behind resilience in a mindful way.

Consisting of six modules, you will earn a certificate upon completion of the online course and join an elite group of HR Managers, counselors, therapists, coaches, teachers and healthcare workers who are all passionate about helping others build-up their resilience.

Resilience Strategies for Coping and Bouncing Back Stronger

It’s also important to be aware of counselor burnout, according to Irene Rosenberg Javors, a psychotherapist in private practice in New York City.

According to Javors, there are some basic tips therapists can follow that can act as a toolbox for developing strategies for resilience skills for combatting fatigue and burnout. (Javors, 2015)

Self-care plan for therapists who experience counseling burnout:

- Exercise.

- Make time for solitude.

- Engage in positive self-talk.

- Get out more and experience life.

- Learn from failure.

- Cultivate both humor and curiosity.

- Have realistic expectations for yourself and your client.

It can be exhausting working with those who are struggling in life. As therapists, it’s important to remember to engage in good self-care habits to prevent burnout. These may seem like simple tips, but they are important ones to keep in mind.

Exercise provides a wonderful opportunity for stress relief. Doing some kind of daily exercise like taking a walk or doing some stretching or yoga can go a long way to helping you cope with counseling burnout.

It’s also important to make time for solitude and remember to engage in positive self-talk. A therapist is literally entering into a client’s world, which can be psychologically intensive.

Because of that, it’s important to take some time to detox and self-reflect. Taking time to meditate, journal and to repeat positive suggestions can go a long way to helping you feel more balanced.

There will be setbacks and failures over time, so it’s also important to learn when to take a step back and spend time with family and friends. When all else fails, the best strategy might be one of humor and curiosity because it helps you remember that learning to be more resilient is a process.

Different Types of Resilience

According to Genie Joseph, M.A. adjunct professor at Chaminade University in Hawaii, and the creator of the Act Resilient program, there are three basic types of resilience (Joseph, 2012).

1. Natural Resilience

Natural resilience is that resilience you are born with and the resilience that comes naturally. This is your human nature and your life force.

Those with natural resilience are enthusiastic about life’s experiences and they are happy to play and learn and explore. Natural resilience allows you to go forth and do your best even if you get knocked down and taken off track.

One example of natural resilience is that of young children under the age of seven. Assuming they have not had any major trauma in life, children of this age typically have an abundant and inspiring approach to life.

2. Adaptive Resilience

Adaptive resilience is the second type. This might also be thought of as ‘trial by fire.’ This occurs when challenging circumstances force you to learn and change and adapt. Learning how to roll with life’s punches can help you build resilience and grow stronger as a result.

3. Restored Resilience

The third type of resilience is known as restored resilience. This is also known as learned resilience.

You can learn techniques that help build resilience, and, as a result, restore that natural resilience you had as a child. Doing so can help you deal with past, present and future traumas in a healthier fashion.

Each of these methods can be thought of as a resilient tank. Although it would be great if someone were strong in all three types of resilience, it’s not always necessary. Greater amounts of resilience in one type can compensate for lower amounts in others.

Stress and trauma tend to lower resilience over time, especially multiple repeated incidents of trauma. Trauma tends to get stuck in the brain leaving you on high alert or fight or flight mode continually. This can continue to manifest, even if the trauma is no longer present.

Being in a constant state of trauma can be emotionally and physically draining.

Each of us is, in essence, hard-wired for survival. The oldest part of your brain, the reptilian brain, is always working to protect you and guard you. While this may have served the caveman well, it doesn’t necessarily help you feel calm or relaxed.

Dr. Herbert Benson, director emeritus of the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital has devoted much of his career to learning how people can counter the stress response.

Benson recommends several techniques that can help elicit the relaxation response, which includes:

- Deep abdominal breathing.

- Focusing on a soothing word like peace or calm.

- Visualizing a tranquil scene like a beach or a park.

- Engaging in repetitive prayer.

- Doing something physical like Yoga or Tai-Chi.

Many people find it hard to manage stress, because stress has become a way of life. A certain amount of stress can serve as a motivating factor, but a little goes a long way.

When you sense danger, whether it is real or imagined, your body’s fight or flight response and your nervous system kick into high gear.

Your body is well-equipped and even hardwired to handle most types of stressful situations but too much stress can cause you to break down. In a sense, stress is your body’s warning system and a signal that something needs to be addressed.

The relaxation response is a simple technique that you can learn that can help you counteract the toxic effects of chronic stress. It slows your breathing rate, relaxes your muscles and can even help reduce your blood pressure.

Chronic stress can take a toll on your mind and body. According to the Harvard Medical School, low-grade chronic stress can even lead to things like high blood pressure, increased muscle tension and an increased heart rate. (According to Harvard Medical School, 2011)

People who have low resilience may feel:

- Depressed

- Victimized

- Demoralized

- Hopeless

- Disconnected

- Tired or fatigued

- Stressed out

- Find it difficult to continue

What are the Key Components and Elements of the Resilient Life?

According to Shing (2016), one major factor that contributes to resilience is the experience of harnessing positive emotions, even in the midst of an especially trying or stressful time.

Positivity improves resilience in a number of ways according to Shing. First, positive emotions help you build up social, psychological, and physical resources over time, which could help you develop coping skills during future times of stress.

According to Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 1998), positive emotions can help broaden your momentary thoughts, actions, and attention to your surroundings. One example of this is the emotions of joy and interest, which help encourage you to approach loved ones and forge stronger bonds and interpersonal connections.

Positive emotions help build personal resources, which can act as a buffer from psychological distress in stressful situations. Positive emotions may even undo the harmful effects of negative emotions when experienced in the midst of a stressful situation.

Beyond positive emotions, resilience is also associated with the experience of autonomy, mastery, and vitality (Shing, 2016) This can help you be more effective at managing challenging tasks and help you live life with more energy and vitality.

Decades of research in well-being suggest that satisfaction in life may not solely be derived from positive emotions alone, but also through feeling a sense of independence and competence, as it pertains to personal goals and values.

This tendency is known as eudaimonic well-being and it has to do with your individual perception of fulfillment in life. This eudaimonic perspective on resilience is coupled with other psychological constructs as well, such as hardiness.

Those who are hardy tend to possess a greater sense of control over their surroundings and event outcomes. As a result, they view stressors as less distressing overall. Those who are hardy also tend to believe they have more personal resources at their disposal, which helps them feel more resilient.

Henry Emmons M.D. talks about creating the chemistry of calm. As an integrative holistic psychiatrist Emmons has worked with thousands of patients, many with severe disabling conditions.

Emmons has treated many of his patients with medications, but also believes there are other factors for healing and recovery beyond medication.

Emmons believes that is within our human nature to be resilient and to be able to face the stressors and losses of life. There are things we can do according to Emmons to help bolster our skills of resilience. These are known as the seven roots of resilience.

Seven Roots of Resilience

- Balancing brain chemistry.

- Managing energy.

- Aligning with nature.

- Calming the mind.

- Skillfully facing emotions.

- Cultivating a good heart.

- Creating deep connections.

Emmons also refers to something called the whole person change process, as a way to build resilience. Emotions such as anxiety and depression affect both the emotional and physical body in a sense. Because of this, all aspects of yourself need to be incorporated into the healing process.

The whole person change process involves several principles. The first core principle is the idea of the pathway. This pathway leads to a more joyful and resilient life and it also requires a dose of self-acceptance.

This is much more than a simple self-improvement project. It involves accepting yourself and your life exactly as they are at this moment in time.

This is the opposite approach of someone who is continually striving for self-improvement. Self-improvement often involves criticism and a drive to be better.

The Japanese call this idea of the tension created by acceptance and the desire for change ‘arugamama‘, or a state of unconditional acceptance (Ikigai Tribe, n.d.).

This means accepting yourself and your life in the moment. This can also be combined with the intention to act in positive ways to create change.

The next core principle of the whole person change process is the idea that change begins within. This might involve honoring yourself and being willing to listen deeply. It might also involve connecting mindfully and compassionately with your inner suffering.

The next core principle is the idea of being resistant to change.

Some amount of resistance is natural and normal, but it must be dealt with if you have a desire to build resilience. The ability to look deep within and look at even those parts of yourself that are resistant is an important part of this process.

Change is a process and a messy one at best. Looking at change as a process is the next principle.

The truth is that change is not a simple linear process for most people. We don’t always experience continuous and sequential improvement. Each of us imagines that perfect life, but we usually experience setbacks along the way. Being resilient can help you manage your expectations.

Change often happens with connections, which is another core principle. In the individualistic Western culture, the onus is often put on the individual. Aligning with this principle means accepting the role of others in your pursuit of success.

Success often involves building a network of connections that can help you achieve your goal. This network might include family, friends or those in the community.

An Example of Resilient Behavior

There are many examples of resilient behavior. Some characteristics of resilient behavior include:

- Viewing setbacks as impermanent.

- Reframing setbacks as opportunities for growth.

- Recognizing cognitive distortions as false beliefs.

- Managing strong emotions and impulses.

- Focusing on events you can control.

- Not seeing yourself as a victim.

- Committing to all aspects of your life.

- Having a positive outlook on the future and developing a growth mindset.

One example of viewing a setback as impermanent would be a salesperson losing a client. They could either look at this as a troubling event or as something that is only temporary. In the end, losing one client, even a large one, is not the end of the world. Staying flexible and having some perspective, can help you realize that there are millions of clients for you to attract.

Reframing is another wonderful technique. Let’s say someone went on a job interview but didn’t get the job. A resilient person would realize that perhaps that wasn’t the job for them. They would pull their resources together and begin looking at alternative options for opportunities.

Cognitive distortions also come into play. Cognitive distortions are basically false beliefs. These are things we convince ourselves are true which reinforce negative thinking. The challenge is in reframing these distortions into a more resilient frame of mind.

One example is someone who is experiencing a flight delay on an airline. A non-resilient person might think that bad stuff always happens to them. They might also think a flight delay is terribly inconvenient. As a result of this thinking, they might then experience anger or stress.

A resilient person could change their thinking, upon recognizing the negative frame of mind. As a result, they could tell themselves that instead of getting anxious they could stop and have a nice meal or read a good book. These new resilient thoughts can help them manage the inconveniences of life and reduce stress.

Managing strong emotions and impulses is another key factor in resilience. Let’s say someone gets angry. They could either take their anger out on someone nearby or learn to move on and stay focused.

Focusing on events you can control is another great example of resilient behavior. Some things are simply out of our control. Traffic would be one of those things. You can either get angry and yell at fellow drivers, or turn on some music or think of new ideas for your next project. The choice is yours.

Not seeing yourself as a victim is also key. If you continually see yourself as a victim in life, you will keep building on that mindset. A resilient person would understand that sometimes things just happen. They are not a victim.

Committing to all aspects of your life means understanding that everything in your life is interconnected. What this means is that there isn’t any one thing that will suddenly make you happy. For example, getting the perfect job or finding that perfect love relationship may not be enough to counteract other difficulties in life.

A resilient person understands that success or failure in one area of life often affects all the other areas of life as well.

Having a positive outlook of the future and developing a growth mindset is probably one of the simplest things you can do to build resilience. Cultivating a growth mindset involves the desire to be open and adaptable and learning to change.

A Take-Home Message

There are many ways to build resilience so that it becomes your natural tendency. Try some of these strategies the next time you feel your resilience needs a boost.

- Turn off the news and seek other sources of inspiration.

- Allow yourself to express and feel your emotions. Sometimes having a good cry can be emotionally cleansing.

- Take a walk and get moving. Exercise and movement can help increase your energy level, and release endorphins into your system.

- Remember a time when you felt resilient in the past. Tap into what allowed you to find a sense of courage, strength, and hardiness.

- Talk with someone you love and trust. Have a meaningful and honest conversation.

- Take some time off to recharge. Unplug the electronic devices and give yourself a moment to rest and reflect.

- Think of someone who exudes resiliency and model his or her behavior.

- Go within and connect with your higher power through meditation or prayer.

- Write it down. Writing down your thoughts and feelings can help you feel better about where you are on this journey.

- Reconnect with others and help build their resiliency.

- Be kind to yourself. Have some compassion and ease up on your expectations.

- Listen to empowering music.

- Take some deep breaths. Breathing deeply is very healing and cleansing.

- Take some inspired action. When you’re feeling overwhelmed, doing one small thing can help you move forward.

- Practice mindfulness in your day-to-day life. The more you practice being in the moment the happier and more joyful you will feel.

- The moment you start believing that you can bounce back is the same moment things will start going your way. Your belief is everything. You can learn to be more resilient.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Resilience Exercises for free.

- American Psychological Association. (2018). The Road to Resilience. [Online]. [18 December 2018]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx

- Cohen, H. (2017). What is Resilience? [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://psychcentral.com/lib/what-is-resilience/

- Compas, B. E., Banez, G. A., Malcarne, V., & Worsham, N. (1991). Perceived control and coping with stress: A developmental perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 47(4), 23-34.

- Conner, K. M., & Jonathan, D. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale (CD‐RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76-82. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- Emmons, H. (2010). The Chemistry of Calm: Restoring the Elements of a Resilient Life. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-chemistry-calm/201010/the-chemistry-calm-restoring-the-elements-resilient-life

- Ey., S. (n.d.). Resilience Building Plan Worksheet. Retrieved December 22, 2018, from https://www.ohsu.edu/people/sydney-ey/CDB7A65DBCA64011AAFB2DAEC0F57C07

- Friedman, H. L., & Robbins, B. D. (2012). Humanistic Psychologist. 40(1), 87-102. 16p.

- Harvard health publishing. (2018). Understanding the stress response. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response

- Horneffer-Ginter, K. (2013). 25 Ways to Boost Resilience. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/design-your-path/201305/25-ways-boost-resilience.

- Igikai Tribe. (n.d.) Arugumama as it is. Retrieved from https://ikigaitribe.com/blogpost/arugamama-as-it-is/.

- Javors, I. R. (2015). Annals of Psychotherapy & Integrative Health. p1-2. 2p., Database: Academic Search Complete

- Joseph, G. (2012). The Three Types of Resilience. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: http://act-resilient.org/Site/Blog/Entries/2012/8/28_The_Three_Types_of_Resilience.html

- Martin, B. (2016). Fight or Flight. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://psychcentral.com/lib/fight-or-flight/

- Marter, J. (2021). Mental Health First Aid. Retrieved from https://www.joyce-marter.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MHA-Mental-Health-First-Aid-Bulidling-Resilience-Positive-Mental-Health-2.pdf

- Masten, A. S., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205-220.

- Rosenberg Javors, Irene, M.Ed.; LMHC is a psychotherapist in private practice in NYC. She is the author of ‘Culture Notes: Essays on Sane Living’ (2010). Contact her at ijavors@gmail.com Cultivating Resilience: Tips for Therapists.

- Serani, D. (2011). Living with depression: Why biology and biography matter along the path to hope and healing. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Shing, E. Z, Jayawickreme, E. & Waugh, C. E. (2016). Contextual Positive Coping as a Factor Contributing to Resilience After Disasters. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(12).

- Southwick et al. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(25338).

- Tartakovsky, M. (2016). Therapists Spill: How to Strengthen Your Resilience. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://psychcentral.com/lib/therapists-spill-how-to-strengthen-your-resilience

- Waters, B. (2013). 10 Traits of Emotionally Resilient People. [Online]. [12/18/18]. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/design-your-path/201305/10-traits-emotionally-resilient-people

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

I would love a copy of this book on resilience if there is a book available. And if so where can I purchase a copy.

Hi Welton,

Thank you for your question. I’d love to help.

Could you specify exactly which book you’d like to purchase? Then I can help you find a link.

Thanks in advance.

-Caroline | Community Manager

hello maam

your article was very informative and effective. I am Planning for a research in this topic can you plz tell me how do i relate it to wellbeing of employees . How can i test it

Hi Sujatha,

So glad you found this post useful. So you’re looking to assess resilience as a predictor of wellbeing? Your approach should depend, in part, on whether you plan to run a natural field study or an experiment. For instance, if you’re interested in an experiment, you could look at running some resilience training with staff and then measure changes in subjective well-being pre- and post- the training.

For advice on how best to measure wellbeing in this context, definitely take a look at our dedicated blog post on subjective well-being scales.

– Nicole | Community Manager

Very impressive nd helpful. And can relate totally with this.

Amazing work.

This is one of the best articles on resilience, I have read, well done professor Leslie for posting such a good articles to motivate people. It is real community help to build positive energy.

Narendra Kushwaha.