What Is Motivational Interviewing? A Theory of Change

Conversations about change occur all the time.

Conversations about change occur all the time.

They can be related to just about anything and can happen with friends and family or with a provider at a routine health visit.

During these conversations, people may voice various reasons for why they want and don’t want to change. In other words, they may be feeling ambivalent about change, which is entirely normal and a step included in the change process (DiClemente, 2003; Engle & Arkowitz, 2006).

What if we could navigate these conversations in a way to help others change for their benefit? What if we could do this in a way that wasn’t a gimmick or coerced, but completely supportive and encouraging?

Knowing that it is possible to have conversations that spark change and assist people to feel motivated and empowered, we look into the theory behind Motivational Interviewing and how we can use it for positive change.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

What Is Motivational Interviewing? A Scientific Theory

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based treatment used by providers all around the world to explore clients’ ambivalence, enhance motivation and commitment for change, and support the client’s autonomy to change.

The approach allows clients to identify their reasons for change based on their own values and interests. Providers can decrease the client’s resistance or defensiveness by taking a seat alongside their clients, as both are considered experts in this approach.

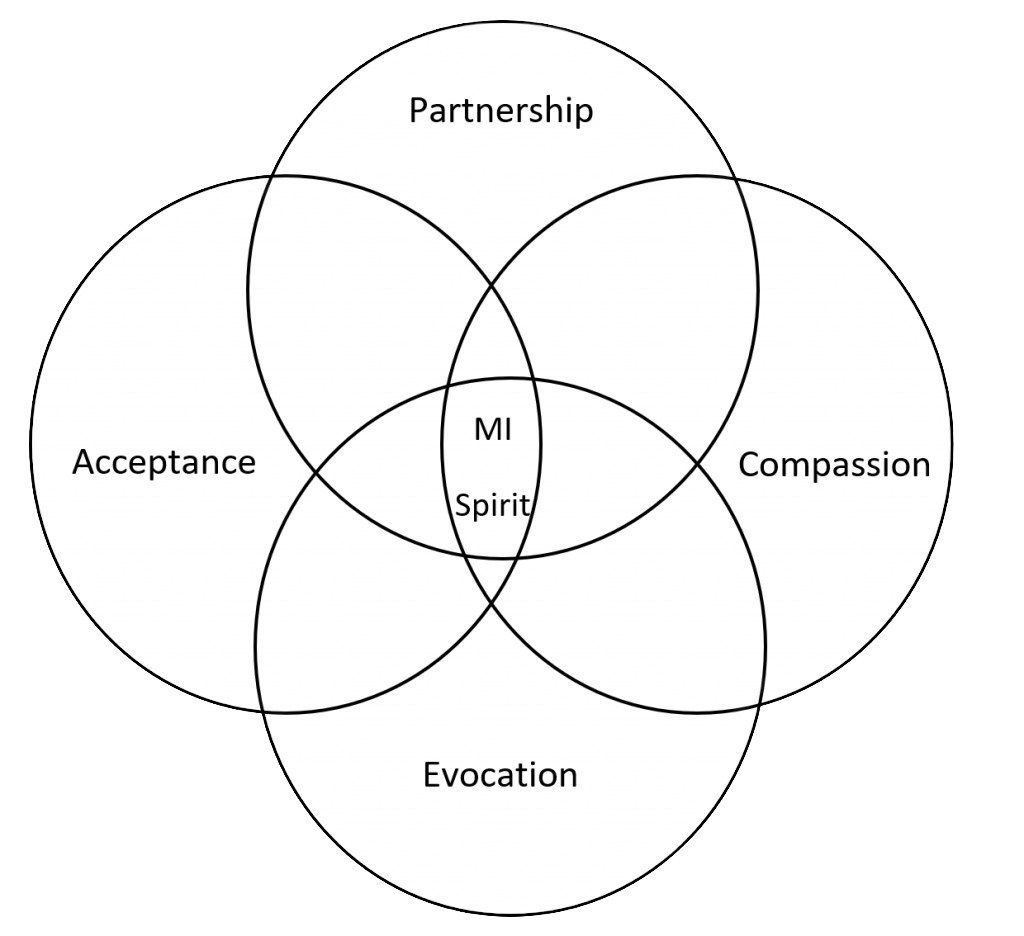

A layperson’s definition of MI would be “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). This collaborative conversation includes the spirit of MI: partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation. The spirit of MI is based on the principles of Carl Rogers’s client-centered counseling (Rogers, 1965).

For change to occur in the conversation, unconditional positive regard is essential.

An acceptance of this other individual as a separate person, a respect for the other as having worth in his or her own right. It is a basic trust – a belief that this other person is somehow fundamentally trustworthy.

(Rogers, 1980)

The spirit of MI, combined with the four processes and core skills, has been used worldwide in various settings to assist with changing behavior.

Motivational Interviewing was developed in the 1980s for individuals struggling with addiction and is now generalized for use with a wide range of behaviors from managing chronic diseases, promoting oral health practices, preventing college dropout, and decreasing children’s TV time.

The development of MI includes the combination of Client-Centered Therapy, the Self-Determination Theory, and the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of behavior change.

Motivational Interviewing provides an environment with respect for clients, worth in what they contribute to the discussion, consideration of their autonomy and volition to change (or not change), and an understanding of their readiness for change.

Client-Centered Therapy

Humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers developed the Client-Centered approach, which emphasizes having unconditional positive regard with clients. This concept is highlighted as Absolute Worth in the MI spirit of acceptance, which is explained more below.

Providers can hold an attitude of acceptance and have respect for their clients’ worth. This attitude of acceptance is without judgment and allows people to feel accepted for who they are, allowing them the space to naturally make changes that benefit them and align with their values.

Therapists can improve their skills and attitude of acceptance by reviewing the worksheets in our Unconditional Positive Regard article.

Self-Determination Theory

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) emphasizes the distinction between types of motivation, intrinsic or extrinsic, and how that influences behavior. Additionally, the theory considers the client’s autonomy to choose, perceived competence to make a change, and the social context.

According to the SDT, when someone feels autonomous to control their own behavior and has the knowledge and skills to achieve the desired outcome, then they are more likely to put in the effort and persist in changing that behavior (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

The social context can further encourage or prevent behavior change. For example, suppose a client is speaking with their provider about decreasing their alcohol use, and the provider assists the client to explore why they want to change their behavior. The provider may ask how they can decrease their use and identify examples of making decreases in the past; then the client may be more inclined to try and decrease their use.

However, if the provider tells the client that they should decrease their use and how to do it, then the client may feel that this change is not their choice, unsure of how to start, and unsupported with making changes.

Transtheoretical Model

The Transtheoretical Model of behavior change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984) was developed to understand how ready people are to change. Here you can learn more about the specific stages of change.

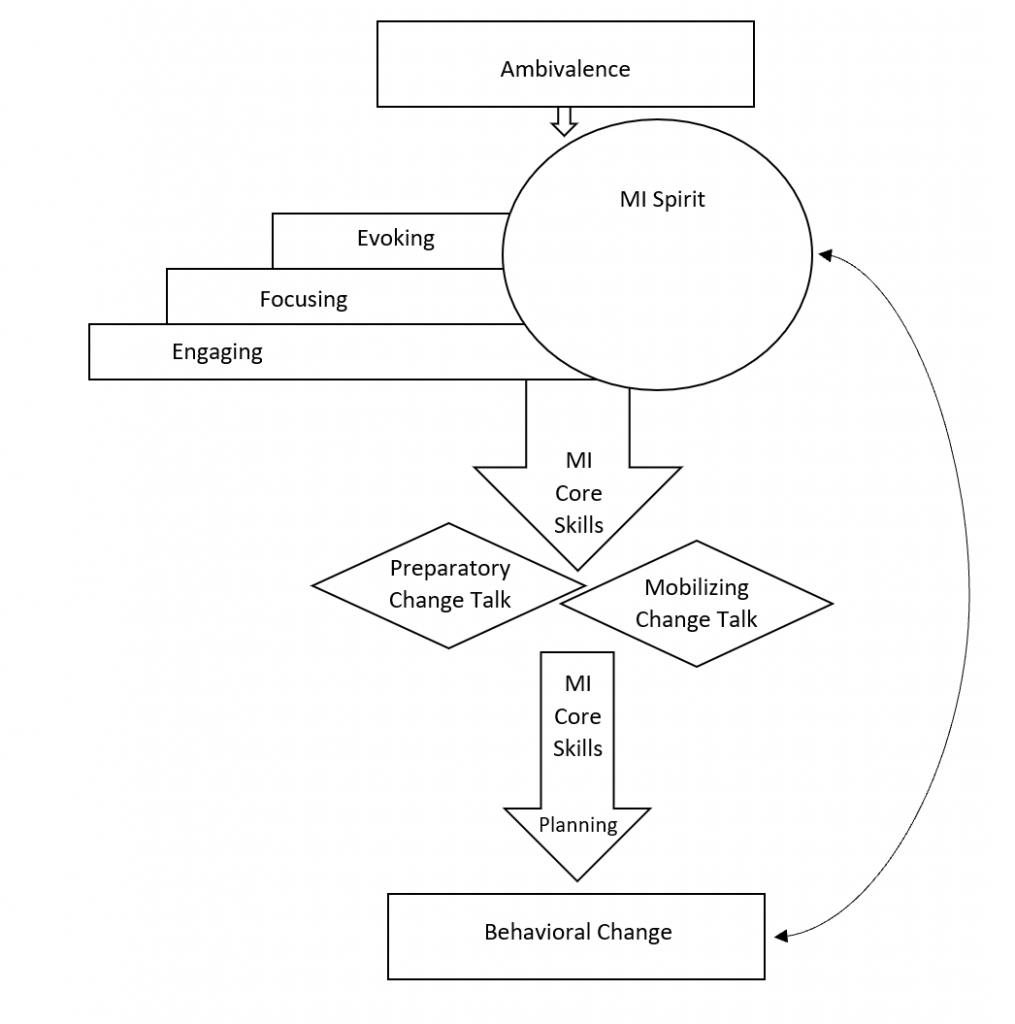

The TTM relates to MI such that the client’s readiness, or what stage of change they’re in, can be considered throughout the four processes of MI. Different MI techniques can be used depending on the individual’s readiness for change. For example, if a client is in the pre-contemplation or contemplation stages, they may be voicing more preparatory change-talk statements, e.g., “I want to be more active.”

Providers can proceed with the evocation process to strengthen the client’s amount of change talk. If a client is in the preparation or action stages, they may be voicing more mobilizing change-talk statements, e.g., “I am going to take a walk this evening,” and providers can assist with the planning process.

The Basics of MI: A Model

To understand the basics of motivational interviewing, we explain the MI spirit, share the four processes, and also mention the core skills.

The four aspects of the MI spirit

The MI spirit consists of partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation.

Figure 1. The spirit of MI

Partnership emphasizes how MI is used with and for someone to engage in an active conversation between two experts.

In MI, there is a collaboration between the provider and the client. Providers must sit with the reality that they don’t have all the answers and need their client’s expertise on how change would look in their lives.

The provider is not trying to convince, trick, or argue why a client should change. Instead, providers are guiding, listening, and trying to understand the client’s circumstances.

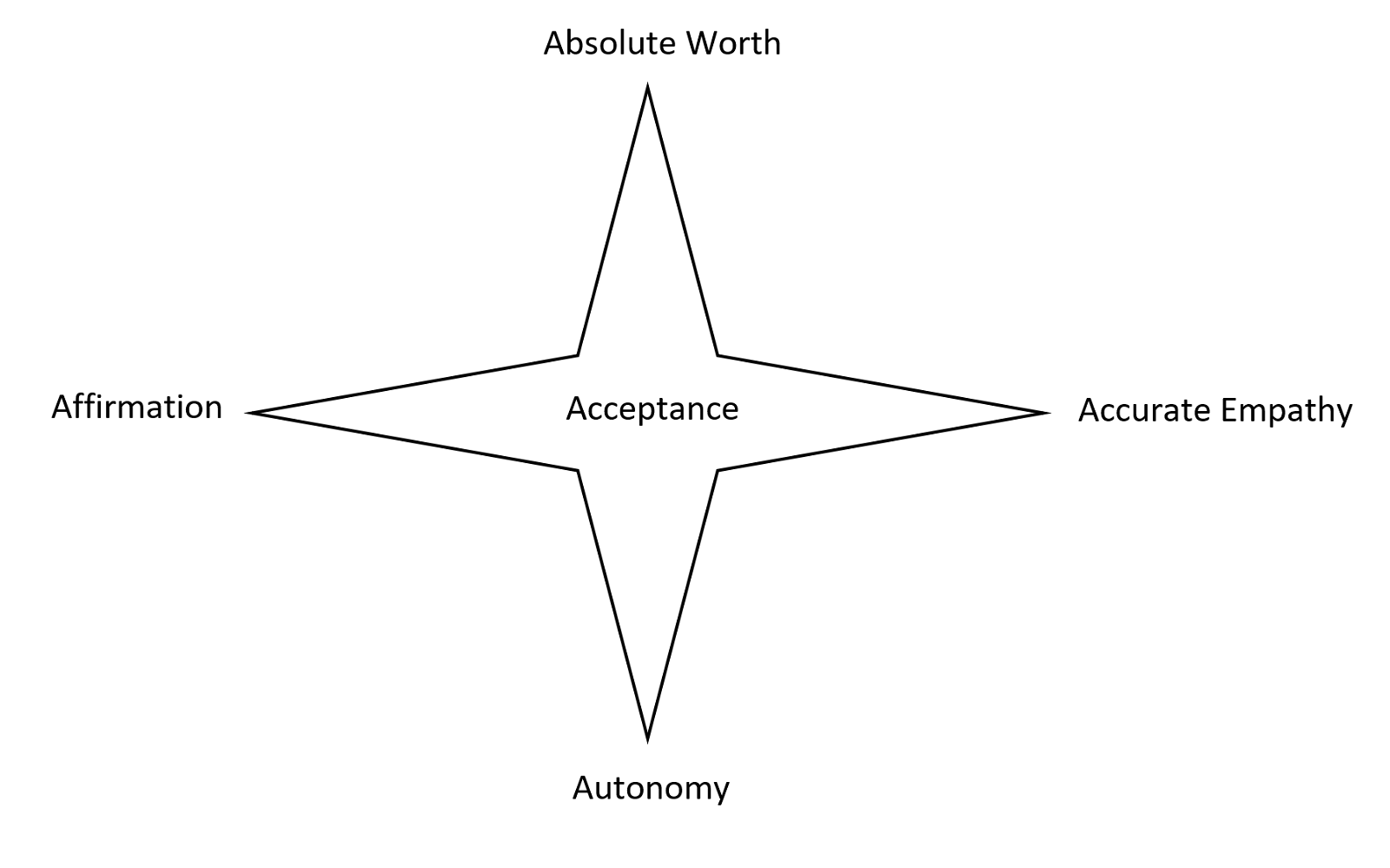

The four aspects of acceptance

Acceptance highlights the importance of respecting what a client contributes to the partnership.

There are four aspects of Acceptance:

- Absolute Worth

- Accurate Empathy

- Autonomy Support

- Affirmation

Collectively, these four client-centered conditions make up the MI spirit of acceptance.

“One honors each person’s absolute worth and potential as a human being, recognizes and supports the person’s irrevocable autonomy to choose his or her own way, seeks through accurate empathy to understand the other’s perspective, and affirms the person’s strengths and efforts.”

William Miller

Figure 2. The four aspects of acceptance

Absolute Worth and Accurate Empathy highlight the work of Carl Rogers and the conditions critical for change.

Absolute Worth emphasizes Rogers’s concept of unconditional positive regard, such that when people are accepted without judgment, they are free to make changes.

Accurate Empathy emphasizes efforts to understand a client’s perspective without feeling pity or identifying with them.

Autonomy Support highlights the importance of respecting a client’s autonomy to choose, not to control, persuade, or coerce. This can facilitate change by decreasing a client’s defensiveness and emphasizes the client’s freedom of choice.

Affirmation emphasizes recognition of the client’s strengths and efforts.

Compassion was added to the underlying spirit of MI in the third edition of Miller and Rollnick’s book Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (2013) to highlight the importance of using MI to promote the wellbeing of others and not for our own self-interest or to exploit others.

Evocation is used to assist clients in identifying the wisdom and reasons for changing their behavior. The spirit of MI assumes that clients want and are capable of change. The provider can evoke from their clients why and how to change by paying attention to their current strengths and resources.

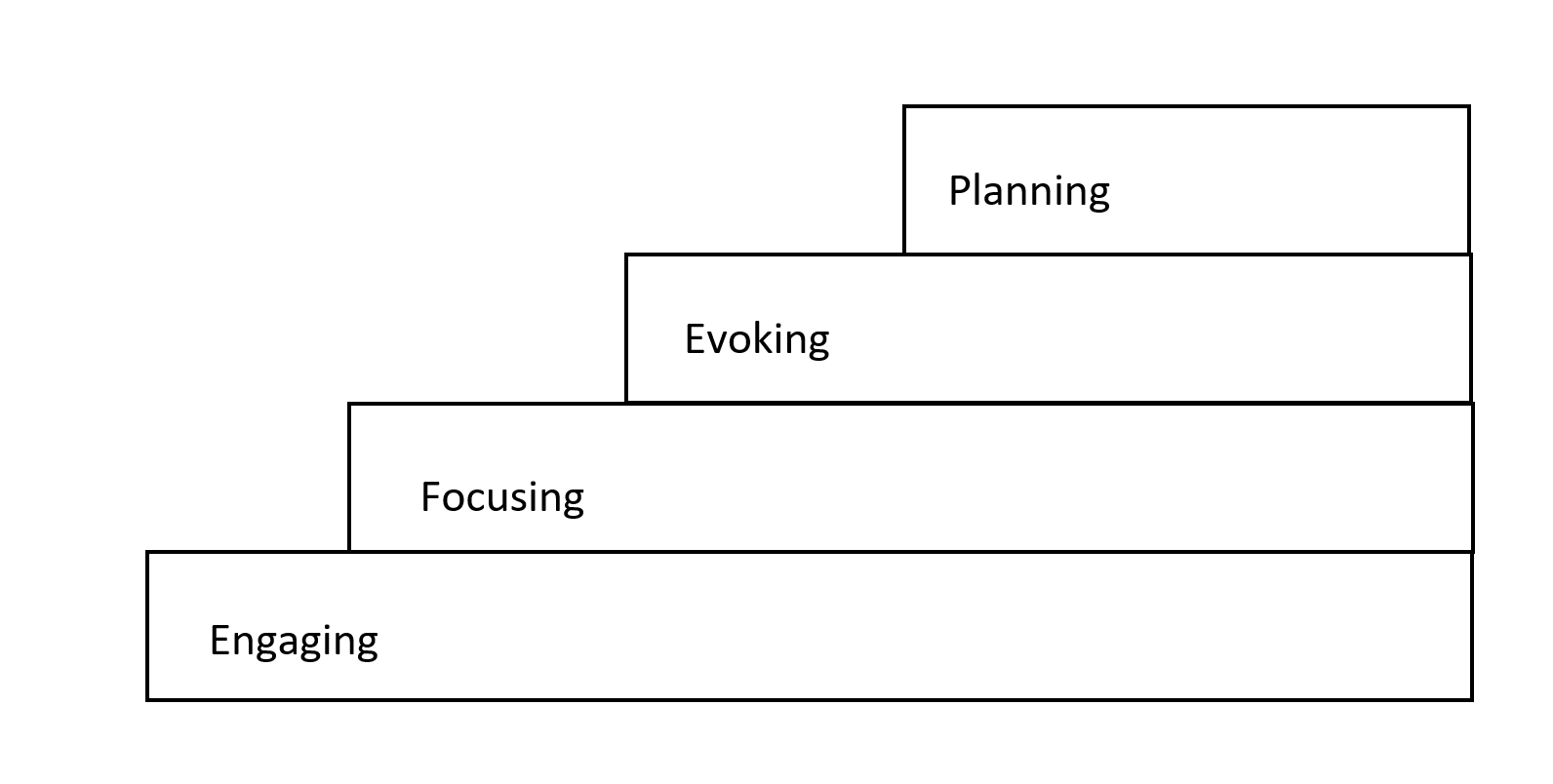

The four processes of MI

The four processes of MI include engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning. They build on one another, overlap, and recur.

Miller and Rollnick (2013) describe these processes as stairs:

“Each later process builds upon those that were laid down before and continue to run beneath it as a foundation. In the course of a conversation or case, one may also dance up and down the staircase, returning to a prior step that requires renewed attention.”

Figure 3. The four MI processes

Engaging is the process where the working partnership is established and the focus is on building rapport with clients. It is more than being kind to clients.

Providers must be in tune with assisting their clients in feeling comfortable and engaged in establishing a mutually trusting and respectful relationship. When a good working partnership is established through the engaging process, clients are more likely to return and make changes.

Focusing is used to assist providers and their clients with clarifying an agreed-upon direction. Both the provider and client may have their own agendas. However, focusing allows the working partnership to collaborate on finding a common direction toward change. This can be done by presenting a clear set of possible topics to focus on during the conversation.

Evoking is used by providers to help clients find and voice their own motivations for change. Providers can explore this with clients by asking open-ended evocative questions that elicit change talk, helping clients identify why they want or need to change, having clients voice what they can do to change, and developing discrepancy between the client’s goals and values and their current behavior.

Planning can begin when a client expresses readiness to change and the conversation becomes more about when and how to change. It involves identifying a plan of action and includes the spirit of MI and the other processes of engaging, focusing, and evoking.

The core skills used in MI include:

| Core skills: | |

|---|---|

| Asking open questions | Questions that aren’t easily answered with “yes or no” but allow elaboration and elicit change talk |

| Affirming | Statements that emphasize the client’s strengths and efforts |

| Reflective listening | Listening to understand the client and using reflective statements to guide clients to resolve their ambivalence |

| Summarizing | Reflecting a recap of the discussion to demonstrate interest and understanding or shift focus |

| Informing and advising (with permission) | Asking the client for permission to provide information or give advice |

Eliciting Change Talk: 5 Goals of MI

Change talk can be preparatory or mobilizing. Preparatory change talk can be elicited when providers explore clients’ desires, ability, reasons, and need to change. Mobilizing change talk can be elicited when providers explore clients’ commitment, activation (willingness, readiness, and preparation), and steps to change.

Change talk can be elicited using the five techniques below.

1. Asking evocative questions

Preparatory evocative questions include exploring desire, ability, reasons, and need (DARN).

Desire questions explore what clients want or wish for life. Examples are provided below.

What do you want from therapy?

How much would you like to drink?

Tell me what you wish were different.

Ability questions explore what clients can and are able to do.

What do you think you could do to… ?

How likely are you to be able to… ?

What ideas do you have to change how much you’re… ?

How confident are you that you could… ?

Reason questions explore why clients want to change.

Why do you want to… ?

What’s the problem with continuing with how things are?

Tell me your top three reasons for…

Need questions explore the client’s urgency for change.

What needs to occur for you to… ?

How urgently does… feel to you?

What do you think needs to change?

2. Using the importance ruler

An imaginary scale ranging from 0 to 10 can be used to explore the client’s level of perceived importance for change. It involves the use of two questions, and the second question is meant to elicit change talk and assist the client to identify why change is important.

“On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates not at all important and 10 indicates the most important thing for me right now, how important is it for you to… ?”

“And why are you at a… and not a (lower number)?”

Although someone may answer the initial question with 0, it is uncommon. In the event that a client reports an importance rating of 0, other evocative questions (desire, ability, or reasons) can be used to explore ambivalence.

3. Querying extremes

Exploring the client’s worst- and best-case scenarios can elicit change talk.

“What can happen in the long run if you continue as you are?”

“What worries you the most about not changing your health habits?”

“What could happen if you were successful in… ?”

“What would be the best results if you did change?”

4. Looking back and looking forward

Helping clients identify how their situation was before engaging in their problematic behaviors and comparing that with their lives currently can elicit change talk. Additionally, assisting clients in visualizing how life could be different can also elicit change talk.

Looking back:

“What was your life like before you gained 30 pounds?”

“How has your weight changed you or prevented you from engaging with your family?”

“Tell me about when things were going well. What changed?”

Looking forward:

“How would you want things to be different in the future?”

“Tell me, if you didn’t have any physical pain, how would your interactions with your family change?”

“How would you like things to be in five years?”

5. Exploring goals and values

Exploring the discrepancy between the client’s current behaviors and the things that they value can elicit change talk. Assisting clients to identify that their behavior is inconsistent with what they find meaningful can enhance their motivation for change.

A Look at the Change Cycle

It is completely normal for people to be ambivalent about making changes in their behavior. There are fluctuating reasons to change and not to change. It’s also important to consider someone’s belief that they’re capable of changing.

Motivational Interviewing can be used to explore someone’s ambivalence for change. With the spirit, processes, and techniques of MI, ambivalence can be resolved. Clients can identify and voice their own desires, ability, reasons, and need for change.

As ambivalence decreases and clients express more readiness and commitment to change, providers can assist clients through the planning process to engage in behavior change.

Figure 4. MI framework

PositivePsychology.com MI Resources

Our site has numerous Motivational Interviewing resources, including specific MI questions, skills, and worksheets, to assist with your client’s readiness to change.

These three articles are particularly helpful:

- 17 Motivational Interviewing Questions and Skills

- The 6 Stages of Change: Worksheets for Helping Your Clients

- Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

While these two worksheets can be equally apt:

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others reach their goals, this collection contains 17 validated motivation & goals-achievement tools for practitioners. Use them to help others turn their dreams into reality by applying the latest science-based behavioral change techniques.

A Take-Home Message

As mentioned initially, conversations about change occur all the time. People inherently want to change and improve their life outlook, lifestyle, and habits. Yet they often fall into a pit of immobility and helplessness.

This is where Motivational Interviewing with its components, processes, and techniques can make a difference. This communication style is client centered, uses empathic listening, and evokes the client’s reasons for change; the conversation is focused on an identified target for change.

At the end of the day, whether or not clients engage in changing their behaviors is up to them. However, as providers, we can focus on understanding why (or why not) and then assist them in exploring why change may be in their best interest – and Motivational Interviewing is the best route to accomplish this.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- DiClemente, C. C. (2003). Addiction and change: How addictions develop and addicted people recover. New York: Guilford Press.

- Engle, D. E., & Arkowitz, H. (2006). Ambivalence in psychotherapy: Facilitating readiness to change. New York: Guilford Press.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (Applications of motivational interviewing) (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1984). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Homeward, IL: Dow/Jones Irwin.

- Rogers, C. R. (1965). Client-centered therapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Rogers, C. R. (Ed.). (1980). A way of being. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

The article is user friendly and easy to comprehend.