Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

Bored or stressed, they are simply our kids.

Bored or stressed, they are simply our kids.

Many traditional public schools do not offer much in terms of autonomy nor allow students to learn at their own speed.

The regimens often undermine students’ inclination to pursue topics that interest them and deeply engage them.

The grading systems used in most schools further discourage them from self-directed learning that is borne out of enjoyment of the process and passion for the subject matter.

Develop a passion for learning. If you do, you will never cease to grow.

Anthony J. D’Angelo

A comprehensive understanding of motivation is desperately needed to:

- Promote engagement in our classrooms

- Foster the motivation to learn and develop talent

- Support the desire to stay in school rather than drop out

- Inform teachers how to provide a motivationally supportive classroom climate

This article addresses major topics in the science of motivation as it applies to educational settings and the process of learning in general, and includes examples of motivational assessments for teachers and classroom interventions for students.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Motivation in Education

We all come into the world with a natural curiosity and a motivation to learn, yet some lose those abilities as they grow older. Many factors shape our individual inclinations toward the process of learning, and education is a critical context that can influence our later attitudes toward the acquisition of knowledge and growth.

True learning is a lifelong process. But to continuously achieve, our children must find it enjoyable and rewarding to learn so they can develop a sustained level of motivation necessary for long-term achievement.

Curiosity and motivation to learn are the forces that enable students to seek out intellectual and experiential novelty and encourage students to approach unfamiliar and often challenging circumstances with anticipation of growth and expectation to succeed.

There is no end to education. It is not that you read a book, pass an examination, and finish with education. The whole of life, from the moment you are born to the moment you die, is a process of learning.

Jiddu Krishnamurti

In the context of education, students’ levels of motivation are reflected in their engagement and contribution to the learning environment.

Highly motivated students are usually actively and spontaneously involved in activities and find the process of learning enjoyable without expecting any external rewards (Skinner & Belmont, 1993). On the other hand, students who exhibit low levels of motivation to learn will often depend on the rewards to encourage them to participate in activities they may not find enjoyable.

According to Malone and Lepper (1987), seven factors drive motivation:

- Challenge

- Curiosity

- Control

- Fantasy

- Competition

- Cooperation

- Recognition

Many of these are present in games, but more on that later. Current trends in educational psychology draw attention not only to cognitive development, but also the students’ motivation and preference as the fundamental factors in fostering effective learning and achievement.

Lack of motivation, a significant barrier to academic success that exhibits itself through feelings of frustration and annoyance, hinders productivity and wellbeing in the long run. Several factors influence the motivational level in learning, such as the ability to believe in the effort, the unawareness of the worth, and characteristics of the academic tasks (Legault, Green-Demers, & Pelletier, 2006).

The following section discusses intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and other related theories in learning motivation.

Theories of Motivation in Education

Motivation itself has a vast scope, and several motivational theories are relevant to the learning domain. The following theories contribute to the essential outcomes of the learning process without being dependent on any other theories in the education domain:

- Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation theory

- Self-determination theory (SDT)

- The ARCS model

- Social cognitive theory

- Expectancy theory

Self-determination theory and the ARCS model are widely utilized in the motivation domain for learning discipline. The implementation level of theories such as social cognitive theory and expectancy theory is still in initial stages but can significantly contribute to understanding motivation in learning as well as other aspects of life where motivation is crucial.

1. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation theory

According to Ryan and Deci (2000), intrinsic motivation defines an activity done for its own sake without the anticipation of external rewards and out of a sense of the sheer satisfaction it provides.

The right level of challenge, adequate skills, sense of control, curiosity, and fantasy are some key factors that can trigger intrinsic motivation. When combined with willpower and a positive attitude, these elements can help sustain motivation over time.

Some studies show that intrinsic motivation and academic achievement share significant and positive correlates (Pérez-López & Contero, 2013). Intrinsic motivation can direct students to participate in academic activities to experience the fun, challenge, and novelty away from any external pressure or compulsion and without expectations of rewards (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Success is no accident. It is hard work, perseverance, learning, studying, sacrifice and most of all, love of what you are doing or learning to do.

Pele

In contrast, extrinsic motivation describes activities students engage in while anticipating rewards, be they in the form of good grades or recognition, or out of compulsion and fear of punishment (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012).

Motivation can be cultivated extrinsically at the initial stage, particularly when it comes to activities that are not inherently interesting, as long as the ultimate goal is to transform it into intrinsic motivation as the learning process unfolds. The rationale for this has to do with a short shelf life and a potential dependence on rewards.

Although extrinsic motivation can initially spark a high level of willpower and engagement, it does not encourage perseverance and is challenging to sustain over time due to hedonic adaptation. Finally, external rewards or compliments undermine the possibility that students will engage in the educational activities for their own sake or to master skills or knowledge.

Nevertheless, both types of motivation have their place in the process of learning. While intrinsic motivation can lead to greater levels of self-motivation, extrinsic motivation often offers that initial boost that engages students in the activity and can help sustain motivation throughout the process of learning over time (Li & Lynch, 2016).

It is no easy undertaking to guide students to learn how to be highly motivated, face challenges, understand the process, and be able to apply their newfound knowledge in real-life circumstances.

2. Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory addresses intrinsic and extrinsic motivation further. It explains it in terms of self-regulation, where extrinsic motivation reflects external control of behavior, and inherent motivation relates to true self-regulation (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

SDT tells us that intrinsic motivation is closely related to the satisfaction of basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and illustrates how these natural human tendencies relate to several key features in the learning process.

Here, autonomy is related to volition and independence, and competence is associated with the feeling of effectiveness and self-confidence in pursuing and accomplishing academic tasks. Relatedness provides the feeling of safety and connectedness to the learning environment, where students’ academic performance and motivation are enabled and enhanced (Ulstad, Halvari, Sorebo, Deci, 2016).

Learning is not attained by chance, it must be sought out for with ardor and attended to with diligence.

Abigail Adams

Self-determination theory evolved out of five other sub-theories that further support its claims.

First, the cognitive evaluation theory, which explains the effects of external consequences on internal motivation, draws our attention to the critical roles autonomy and competence play in fostering intrinsic motivation by showing how they are vital in education, arts, sports, and many other domains.

Second, organismic integration theory and causality orientations theory further explain motivation as occurring along a spectrum, from an amotivational stage toward motivational states where the focus is on competence.

Next, basic psychological needs theory, which classifies human needs into three primary psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness), shows how the satisfaction of those needs is crucial for engagement, motivation, healthy progress, and wellbeing among students (Gagné & Deci, 2014).

Finally, goal contents theory shows the relationship between fundamental needs satisfaction and wellbeing based on intrinsic and extrinsic goal motivation, where intrinsic goals lead to greater achievement and better academic performance, especially within the educational environment (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

3. ARCS model

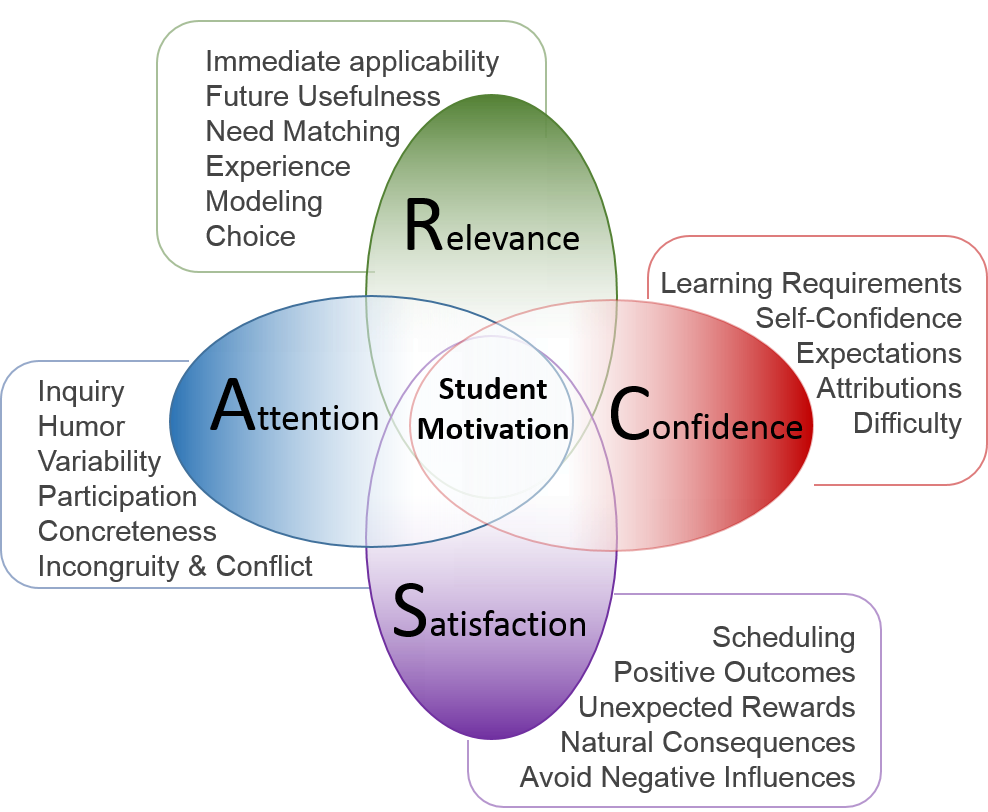

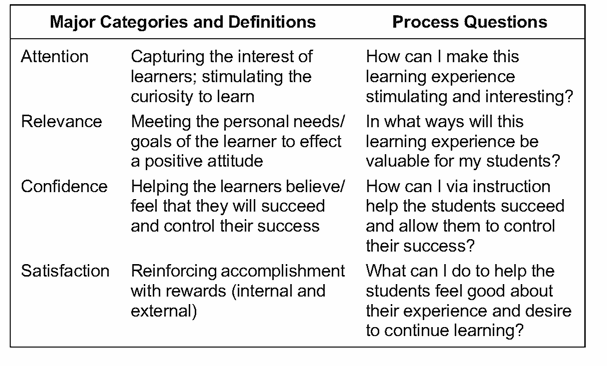

ARCS is an acronym for attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction. The ARCS model is an approach to instructional design that focuses on the motivational aspects of the learning environment by addressing four components of motivation (Keller, 1987):

- Arousing interest

- Creating relevance

- Developing an expectancy of success

- Increasing satisfaction through intrinsic and extrinsic rewards

The ARCS model stresses capturing students’ attention as critical to gaining and sustaining their engagement in learning and shows how this can be accomplished through the use of attractive and stimulating media or learning material that is relevant to their experiences and needs.

It recognizes how confidence is related to students’ anticipation of success and how positive feelings about the learning process lead to greater satisfaction from the acquisition of knowledge (Keller, 2008).

4. Social cognitive theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT), implemented today in various domains from education and communication to psychology, refers to the acquisition of knowledge by direct observation, interaction, experiences, and outside media influence (Bryant & Zillmann, 2002).

It rests on the assumption that we construct meaning and acquire knowledge through social influence, from daily communication to the use of the internet, and explains the relationships between behavior, social and physical environment, and personal factors.

SCT illustrates how people gain and maintain several behavioral patterns and provides basic intervention strategies like interactive learning, which allows students to gain confidence through practice (Bandura, 1989).

5. Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory, originally developed to explain how the work environment can motivate employees, strives to show the relationship between the expectations of success and anticipation of rewards, and the amount of effort expended on a task and how it relates to overall performance (HemaMalini & Washington, 2014).

Simply put, expectancy theory explains motivation as a choice based on the expectation of the results of selected behavior.

The expectancy theory explains motivation in terms of reasons we engage in specific behaviors, where we expect that effort will lead to better performance, which in turn will lead to valued rewards.

In an educational context, this would translate into students’ perception that their effort will lead to good or better performance (expectancy), their belief that their performance will lead to achieving the desired goal and rewards (instrumentality), and lastly, that the value of the rewards is satisfactory and supports the goals of the student (valence; Bauer, Orvis, Ely, & Surface, 2016).

Motivation and Learning

If our kids are motivated, they learn better and retain more of what they learned. Although this sounds obvious, the reality is more nuanced, and the research shows that not all motivations are created equal.

The literature on goal achievement recognizes two primarily and distinctly different types of goals: mastery and performance. Some of our children are driven to master materials, skills, and develop their competence; others strive to perform well in comparison to others (Dweck, 1986; Nicholls, 1984).

Mastery goals and performance goals represent the same overall quantity of motivation, but they are qualitatively distinct types of motivation.

Murayama and Elliot (2011) conducted a series of behavioral experiments to examine how these two different types of motivation influence learning.

In their study, participants were engaged in a problem-solving exercise and received a surprise memory test related to the task. Those in the mastery goal condition were told that the purpose of the task was to develop their cognitive ability, while those in the performance goal condition were told that their goal was to demonstrate their ability relative to other participants.

Members in the performance goal condition showed better performance on an immediate memory test, but when the memory was assessed one week later, those in the mastery goal condition outperformed those who were motivated by competition.

Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.

Mahatma Gandhi

Although the results of the study clearly indicated that performance goals help short-term learning and mastery orientation facilitates learning over time, Murayama felt this needed further testing.

A longitudinal survey data on more than 3,000 children in grade 7 in German schools were analyzed using latent growth curve modeling and showed that items that focus on the performance aspect of learning, where the students said they worked hard in math because they wanted to get good grades, predicted a higher immediate math achievement score.

Similarly, items focusing on the mastery aspect of learning, where students reported investing a lot of effort in math because they were interested in the subject, predicted the growth in math achievement scores over three years (Murayama, Pekrun, Lichtenfeld, & vom Hofe, 2013).

This convergent evidence that mastery-based motivation supports long-term learning, whereas performance-based motivation only helps short-term learning and the underlying mechanisms of this time-dependent effect of motivation is currently being examined with some additional neuroimaging and behavioral experiments (Ikeda, Castel, & Murayama, 2015; Murayama et al., 2013).

Motivation and Creativity

Our students’ ability to generate novel and useful ideas and solutions to everyday problems is a crucial competence in today’s world and requires high levels of motivation and a good dose of creativity.

Although creativity is to some extent tied to personality traits, it is also influenced by the supportive aspects of the student’s environment, sense of mastery of the domain or medium the student is working in (which may or may not influence self-efficacy), and finally by levels of motivation and their intrinsic versus extrinsic characteristics.

Thanks to Theresa Amabile (1996), who studied the creativity of commissioned versus non-commissioned artistic works, we know a lot about the link between intrinsic motivation and creativity.

Csíkszentmihályi, who studied creative and accomplished people for over a decade, concluded that genuinely creative people work for work’s own sake, and if they make a public discovery or become famous, that is a bonus. What drives them, more than rewards, is the desire to find or create order where there was none before.

When talking about students in school, protecting and supporting intrinsic motivation is one important thing we can do to promote creativity and learning. Although we may want to quickly conclude that the higher the student’s intrinsic motivation, the more creative and original they will be, the real explanation of the relationship between motivation and creativity is more difficult than many overly optimistic accounts have claimed.

Real creativity can only emerge once we have mastered the medium or domain in which we work. An idea or product that deserves the label ‘creative’ arises from the synergy of many sources and not only from the mind of a single person, according to Csíkszentmihályi.

Learning and innovation go hand in hand. The arrogance of success is to think that what you did yesterday will be sufficient for tomorrow.

William Pollard

Creativity is an important source of meaning in our lives, as all the things that are interesting, important, and human are the results of creativity. The genuinely creative accomplishment is seldom the result of a sudden insight but comes after years of hard work.

Our educational system emphasizes the use of logic, where one correct statement proceeds to the next and finally to the right solution. While this approach is sufficient most of the time, when we have a particularly tricky situation, it may not give us the leap forward we need.

Thinking outside of the box, or what Edward de Bono (1967) calls lateral thinking, can be used when we have exhausted the possibilities of normal thought patterns.

It is not enough to have some awareness of lateral thinking, de Bono (1995) asserts; we have to practice it. Most of his books consist of techniques to try to get us into lateral thinking mode. Here are a few we can test in our classrooms:

- Generating alternatives — To have better solutions, you must have more choices to begin with.

- Challenging assumptions — Though we need to assume many things to function normally, never questioning our assumptions leaves us in thinking ruts.

- Quotas — It helps to come up with a certain predetermined number of ideas on an issue. Often, it is the last or final idea that is the most useful.

- Analogies — Trying to see how a situation is similar to an apparently different one is a time-tested route to better thinking.

- Reversal thinking — Reverse how we see something – that is, see its opposite – and we may be surprised at the ideas it may liberate.

- Finding the dominant idea — Not an easy skill to master but extremely valuable in seeing what matters in a book, presentation, conversation, and so on.

- Brainstorming — Not lateral thinking itself, but provides a setting for that kind of thinking to emerge.

- Suspended judgment — Deciding to entertain an idea just long enough to see if it might work, even if it is not attractive on the surface.

Creativity results from a complex interaction between a person and their environment or culture. Real learning and creativity require student engagement, which involves a combination of motivation, concentration, interest, and enjoyment derived from the process of learning itself – qualities that are essential to flow (Shernoff, Csikszentmihalyi, Shneider, & Shernoff, 2003).

Motivation at Its Best: The Flow Classroom

Fostering student engagement that leads to the experience of complete absorption in the task at hand, also known as the state of flow, can bring about deeper learning. Although not an easy task, teachers can infuse more flow into their classrooms.

It requires that students connect to their goals, specifically intrinsic goals. Goals such as social connection, self-acceptance, and physical fitness are growth oriented.

In sharp contrast to goals that are driven by judgment or approval of others, intrinsically motivated pursuits are those that are inherently satisfying because they often are likely to satisfy innate psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence.

Shernoff et al. (2003) followed students through different classes to observe what kinds of activities and teacher instruction produced the most flow.

Interestingly, they found that achieving flow was not determined by any particular type of activity but rather by the mix of challenge and support teachers provide. The study showed that student engagement was high when they were appropriately challenged, which usually involved complex goals and high teacher expectations as well as support and positive interactions (Shernoff et al., 2003).

Shernoff et al. (2003) observed that when teachers pointed out the relevance of lesson goals to students’ lives by centering lessons on real-world problems, made sure students had the skills and materials to reach these goals, monitored progress, provided feedback, and developed good rapport with students, their students experienced more flow and learned better.

In addition, teachers who modeled enthusiasm for the material and used humor were particularly engaging to students, even when lecturing. Shernoff believes that learning is about desire rather than capacity and argues that today’s schools, with their focus on grades, fail to take advantage of kids’ intrinsic desires to learn.

If we want kids to get excited about learning and commit to deeper study, they need to be motivated to learn and enjoy the process.

Shernoff (as quoted in Suttie, 2012)

The researchers found that students were most engaged in school while taking tests, doing individual work, and doing group work.

Students were less likely to experience flow when listening to lectures or watching videos. Particularly when the activities were under their control and relevant to their lives, students reported being most engaged and in a better mood.

Shernoff et al. (2003) concluded that teachers could encourage more flow in their classrooms through lessons that offer choice, are connected to students’ goals, and provide both challenges and opportunities for success that are appropriate to students’ level of skill.

Shernoff et al.’s (2003) findings seem to suggest that the chance students will experience flow will often be determined by the person standing at the head of the class. Students’ engagement fluctuates a great deal depending on their teachers. The key, says Shernoff, is for teachers to make learning goals attainable based on the students’ skill levels and to encourage student autonomy while providing positive feedback.

“Teachers would be better off thinking about how they can affect the learning environment and play more of a coaching role instead of thinking about what information they are going to impart,” says Shernoff (Suttie, 2012) and suggests the following approach to the cultivation of flow in the classroom:

- Challenge without overwhelming. An activity must be challenging at a level just above students’ current abilities. If a challenge is too hard, students will become anxious and give up; if it’s too easy, they’ll become bored. It’s crucial to find the sweet spot. Students may require a lesson to be scaffolded, breaking it down into manageable pieces, to find the right balance.

- Create interest through making assignments relevant to students’ lives. Encourage students to discover the relevance for themselves, as interest in the subject is a fundamental part of flow.

- Support their autonomy and encourage choice. When students are given an opportunity to choose their activities and work with autonomy, they will engage more with the task.

- Provide structure by setting clear goals and give feedback along the way. Students help define their goals and remain aware of how or whether their efforts are moving toward the goal.

- Foster positive relationships by valuing their inputs.

- Cultivate deep concentration and foster a feeling of complete absorption by limiting distractions and interruptions.

- Create an experience through hands-on exercises through making things, solving problems, and creating artwork. Stay away from lectures or videos.

- Model enthusiasm for the subject, make them laugh, and speak their language.

All of this resonates with Csíkszentmihályi’s original research on flow, which found that there must be a good balance between the level of challenge required by the activity and the skills of the person engaged in it.

The flow theory explains how, when the challenge is too great, the student can become anxious, and if the task is too easy, the student will be bored. Csíkszentmihályi’s findings also show that to cultivate flow even further, the goal of the activity should be clear and feedback ongoing, so that students can adjust their effort over time.

Shernoff et al.’s (2003) findings were further validated by Ellwood and Abrams (2018), who studied specifically how the promotion of flow experiences can foster enhanced student motivation and greater achievement outcomes.

Clearly defined goals, immediate feedback, and most importantly, the perfect balance between challenge and skills led to greater motivation and ultimately greater achievement. Incorporating the experience of flow was positively related to the success of inquiry-based science (Ellwood & Abrams, 2018).

Motivation and What Gets in the Way

The discussion of student motivation, especially for those who may be reluctant or resistant, would not be complete without understanding the mechanics of what gets in the way.

The learned helplessness theory relies on the components of contingency, cognition, and behavior to explain the motivational dynamics underlying helplessness. The theory of learned helplessness explains behaviors characteristic of lack of self-efficacy and expectancies of no or low control over future outcomes (Reeve, 2018).

It is the opposite of the sense of competence and autonomy and is often representative of low self-esteem and a pessimistic worldview.

Be curious, not judgmental.

Walt Whitman

Its three components explain the mechanism for how helplessness is learned and how it often leads to depression. The contingency component explains the link between action taken by a person and its subsequent outcome, ranging in degrees of objective control available to a person.

The cognition component of learned helplessness refers to our cognitive interpretations, our beliefs, and the associated feelings that amount to a personal sense of control. In the case of learned helplessness, these are characterized by loss of hope, resignation, loss of self-esteem, and fear of global implications of failures and negative events.

Here, the pessimistic attribution styles distinguish those who believe that adverse outcomes were caused by them, that they will endure, and that they cannot be changed or brought under control from those who have an optimistic attitude toward bad outcomes and see them as caused by the environment, temporary, and changeable.

These attributions, in turn, affect motivation and can exhibit themselves in case of learned helplessness through lack of effort in future undertakings, procrastination, and in some instances, through the avoidance of similar situations altogether (Reeve, 2018).

Motivational Resources for Teachers

Unfortunately, lollipops and stickers will probably not do the trick. This requires us to periodically reflect on what is already working so we can tweak our existing motivational strategies and maybe even pick up a few new ones along the way.

It’s possible to help all students, even the most reluctant and resistant, to choose to invest in their learning. The motivation checklist below, courtesy of Mindsteps (2011), is a great way to evaluate where you can improve motivation levels in your classroom, and together with the reflection exercise, these can serve as a roadmap for the future.

Motivation checklist

Build a classroom worth investing in

- I have created a classroom that is most conducive to the way my students learn best.

- I am clear about what currencies the lesson demands.

- I have made sure that the lesson does not privilege my currencies as the only acceptable forms of currency.

- I have worked out ways to make explicit the currencies required by the lesson.

- I have examined my classroom to make sure that I am not unintentionally creating barriers to investing.

- I have removed all classroom barriers to investing.

- I am helping students who do not have the required currencies or a viable alternative to acquire the currencies they need.

- I have built in-classroom structures that offer students autonomy of task, time, team, and technique.

- I have built in-classroom structures that offer students mastery.

- I have built in-classroom structures that offer students a sense of purpose.

- I have built in-classroom structures that foster a sense of belonging.

Uncover and address the reasons students resist

- I have identified students’ reasons for resisting investing.

- I have addressed students’ fear of failure by including specific strategies to build students’ resilience.

- I have addressed a lack of relevance for students by personalizing content.

- I have addressed students’ lack of trust by deliberately building relationships with students.

- I have looked for ways to demonstrate value on students’ terms rather than my own terms.

Ask for the investment

- I have clearly defined the long-term investment goal.

- I have asked for an investment that is directly connected to the goal.

- I have asked for a specific investment.

- I have proposed the highest realistic investment students can make at the time.

- I have proposed a meaningful investment.

- I have helped students set specific goals.

- I have asked these students to make an investment.

- I have held these students accountable to their investment.

- I look for ways to help my students continue to invest in the classroom using their new currencies.

Reflections on motivation

- How do unmotivated students currently behave in your classroom? What do they do (or not do)?

- How do you think these unmotivated behaviors affect students’ individual ability to learn and the classroom environment as a whole?

- Imagine that a miracle occurred and that you walked into class one day to find that all of your students’ motivation problems had been solved. Describe what this would look like for a typical class. What would your students be doing differently?

- Take a closer look at the “miraculously motivated” class you’ve described above. What specific investments of time, effort, and attention do you envision students making?

- How do you think the specific investments you’ve identified would affect your classroom environment?

- How might you respond to students differently if they were suddenly motivated? What specific behavioral changes would they notice in you?

- Describe the last time you saw your “unmotivated” students invest in your class even for a little bit of time.

- Look closer at this motivated episode and consider what about it might have been different. What was different about the activity, the classroom environment, and your behavior that might have motivated your “unmotivated” students to invest in your class? (Mindsteps, 2011).

The secret to motivating your child – Jennifer Nacif

3 State-of-the-Art Interventions

We know from the study of motivation that trying to change personal characteristics within the students themselves is not likely to produce results. Our college students are dropping out of school at a high rate because they feel that the school ignores them and their unique concerns.

This suggests that it would be more helpful to design interventions that provide students with highly responsive relationships, rather than trying to change the students themselves.

Instead of interventions that are geared toward increasing students’ GPA, it would be more practical to design ways to support students’ interest in school, encourage them to pursue intrinsic goals, offer students the opportunity to envision attractive possible future selves, and provide an experience to develop a growth mindset, to name a few.

An effective intervention includes a supportive social context and high-quality interpersonal relationships.

The following three interventions represent three success stories in the effort to translate motivation and emotion theory into convenient state-of-the-art intervention programs.

The first intervention illustrates a needs-based intervention, the second a cognition-based intervention, and the third an emotion-based intervention. See our articles on What Is Motivation?, Motivation Science, and Theories of Motivation for detailed explanations of these components of motivation.

Intervention 1: Satisfying psychological needs

Everyone experiences the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and these three needs energize and vitalize classroom engagement and learning.

Unfortunately, students in many classrooms receive instruction and are asked to write papers, complete projects, and learn new skills in ways that leave their psychological needs unmet.

One group of researchers developed a needs-based intervention program to help teachers develop a motivating style capable of supporting students’ psychological needs.

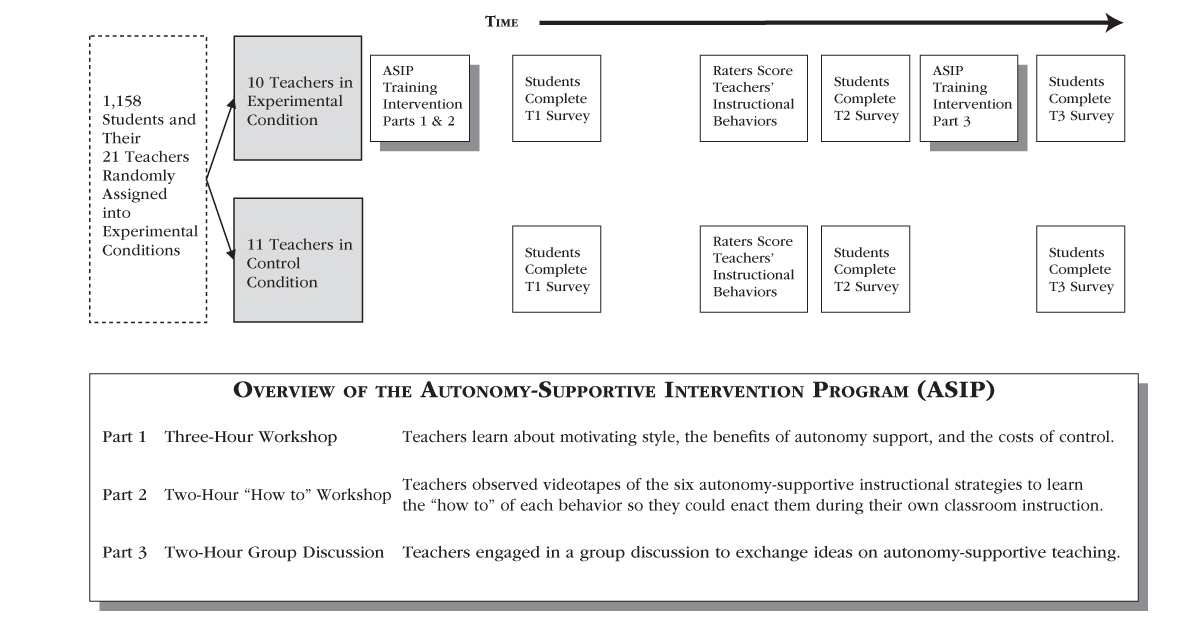

Specifically, they developed, implemented, and tested the merits of an autonomy-supportive intervention program (Cheon, Reeve, & Moon, 2012; Cheon, Reeve, & Song, 2016).

Autonomy-supportive teachers do the following:

- Take their students’ perspective

- Listen empathically to what students say

- Utilize instructional strategies that nurture inner motivational resources

- Teach in students’ preferred way

- Provide explanatory rationale

- Use invitational language

- Display patience

- Acknowledge and accept students’ expressions of negative affect

These are not commonly occurring classroom events, but these instructional strategies can be learned. The step-by-step intervention program was designed to help teachers learn the “how-to” of autonomy-supportive teaching.

The autonomy-supportive intervention program was delivered in three parts.

- Part 1 was a three-hour morning workshop offered before the beginning of the semester. During the workshop, teachers learned about their motivating style, the benefits of autonomy support, and the costs of interpersonal control.

- Part 2 was a three-hour afternoon workshop to learn the “how-to” of autonomy support. Teachers watched videotapes of other teachers (professional actors) modeling the six evidence-based autonomy-supportive instructional behaviors.

- Part 3 was a two-hour group discussion in which teachers shared their actual experiences in trying to implement autonomy-supportive teaching in their classrooms.

To assess the validity and effectiveness of the intervention program, the students completed questionnaires to report their perceptions of their teacher’s motivating style as well as their motivation and classroom functioning throughout the semester.

Also, a group of trained raters visited each teacher’s classroom midway through the semester to rate objectively how frequently teachers used autonomy-supportive instructional behaviors during their instruction.

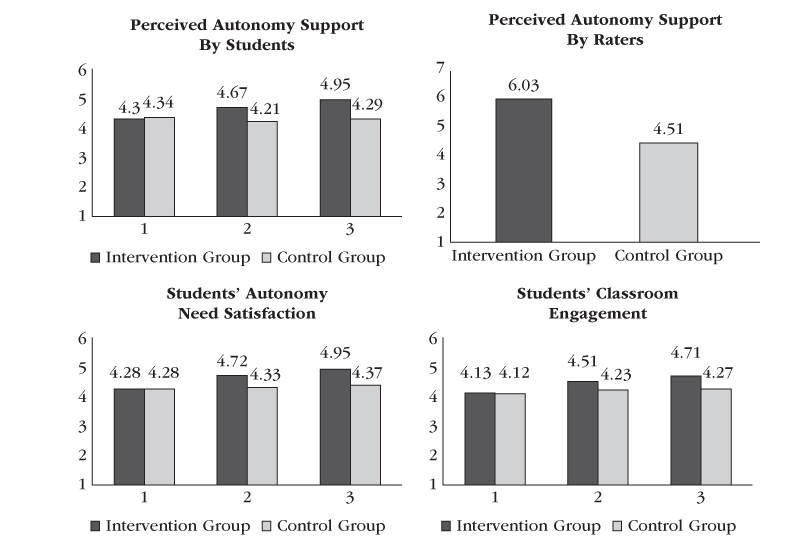

The results below show that the intervention produced its intended effect in helping teachers in the experimental group teach in a more autonomy-supportive way and generated positive benefits.

Overall, this intervention is a success story because it shows that teachers can learn how to support students’ psychological needs satisfaction, and when they do, their students benefit in many important ways, including increased motivation.

The interventions below also translate motivation theory into practical application, although in a somewhat less direct fashion. Nevertheless, they have the potential to improve the social context necessary for motivation to thrive.

Intervention 2: Increasing a growth mindset

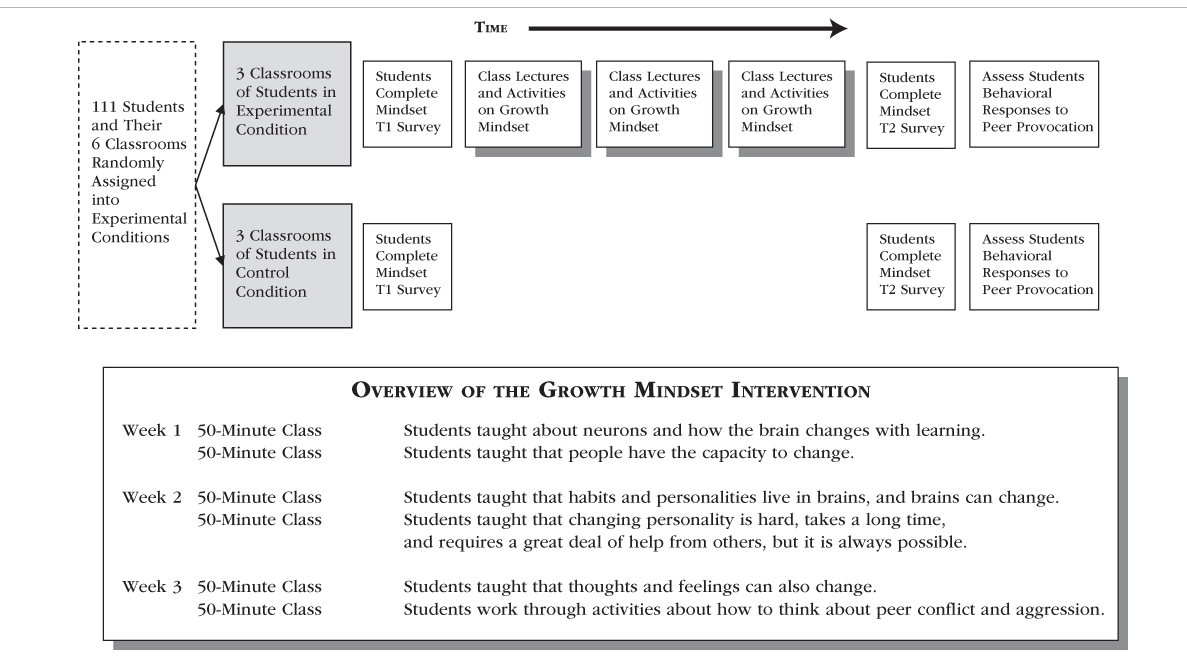

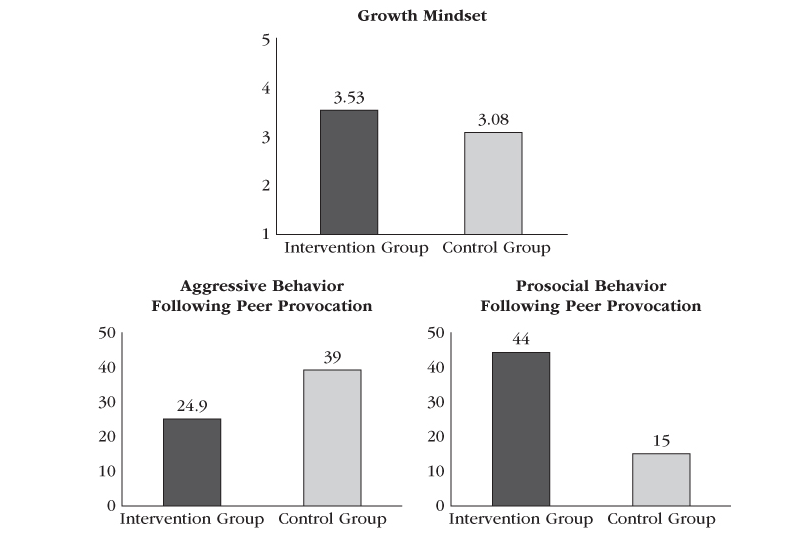

Another state-of-the-art intervention is a cognition-based intervention intended to help a growth mindset in kids in thinking about people’s personalities and was developed by a group of researchers to address adolescent aggression. Specifically, the researchers developed, implemented, and tested the merits of a growth mindset workshop (Yeager, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2013).

Some adolescent aggression is unprovoked, but most occurs as retaliation to peer conflict, social exclusion, and victimization. In a conflict, adolescents generally make a personality-like evaluation of the other person’s character and, as a victim, see the other as an aggressor who cannot change.

This belief often leads to aggressive retaliation; harming the aggressor seems deserved. But when a victim sees the aggressor as someone who can change, then this belief tends to reduce aggressive retaliation and open up the possibility for a prosocial response.

A study designed to test an intervention to increase a growth mindset showed that adolescents who embrace a fixed mindset, a belief that people cannot change their personalities, would be more likely to be aggressive than adolescents who adopt a growth mindset.

Over three weeks, 111 ninth- and tenth-grade students in several different high schools in the San Francisco area attended lectures and engaged in activities to teach them the science of a growth mindset.

They learned about how the brain changes with learning, that personalities can also change because they live in the brain, and that thoughts and feelings can change as well. The students also all engaged in activities to help them think about peer conflict and aggression.

Students also completed a questionnaire assessing the growth mindset two weeks before the start of the intervention and again two weeks after the intervention ended, and played a “cyber ball” activity in which they suffered an experience of peer exclusion.

After the peer exclusion experience, participants were allowed to behave aggressively and retaliate or in a prosocial way and write a friendly note.

Results from the three-week intervention report the evidence that the intervention produced its intended effect:

- Adolescents in the experimental group endorsed the growth mindset significantly more than adolescents in the control group.

- When provoked, adolescents in the experimental group showed more prosocial behavior than adolescents in the control group.

- Teachers rated adolescents in the experimental group as significantly less aggressive than adolescents in the control group.

Overall, the study showed that a school-based intervention that taught adolescents the science of the growth mindset was able to take the anger- and aggression-based edge out of peer conflict so that aggressive retaliation became less likely while prosocial behavior response became more likely.

Intervention 3: Promoting emotion knowledge

The third intervention speaks to the role emotions play in motivational states. Students with unsophisticated emotion knowledge are at risk of developing maladaptive behavior problems such as interpersonal conflict, classroom disruptive behavior, aggressive behavior, and the absence of social competence.

Emotion knowledge involves a capacity to recognize emotional expressions in others, produce a correct label for those emotional expressions, and articulate the causes of basic emotions.

If children could develop their emotion knowledge and learn how to utilize their positive emotions (e.g., interest, joy) better, then they would be better positioned to regulate their negative emotions (e.g., fear, anger) and maladaptive behavior problems.

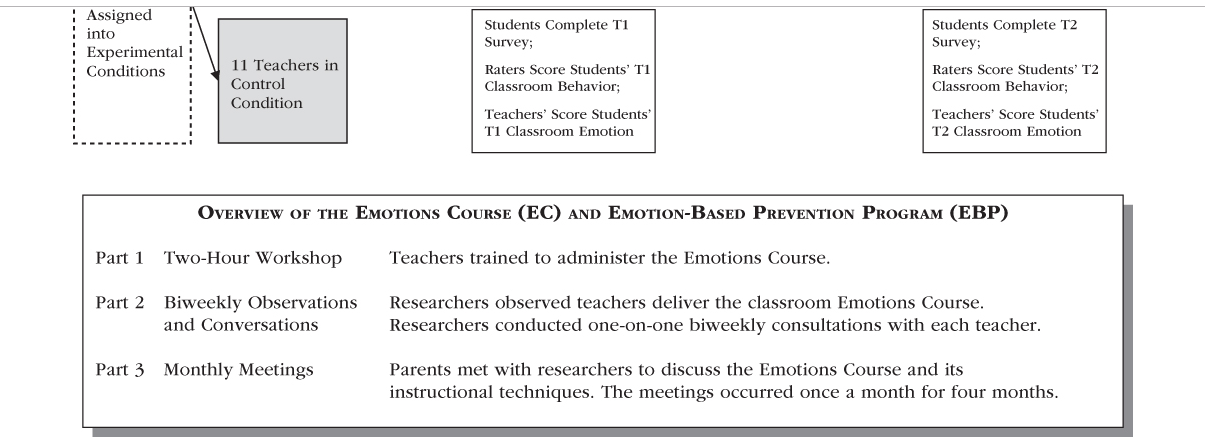

Izard, Trentacosta, King, and Mostow (2004) developed an emotion-based intervention in the form of a preschool program to deliver an “Emotions Course” and an “Emotion-Based Prevention Program” to promote children’s emotion knowledge.

In the Emotions Course, children engaged in activities like puppet shows that provided opportunities to label basic emotions. Children also drew faces of emotional expressions to depict different emotions and their intensity levels.

The point of the Emotions Course was to increase children’s skill in decoding and recognizing others’ emotional expressions.

In the Emotion-Based Prevention Program, children engaged in activities that created mild emotions like reading books about characters who have emotional episodes as teachers helped them articulate their feelings, understand the causes of these emotions, and take appropriate action to regulate them.

To regulate anger, for instance, children were taught to hug a pillow to reduce anger-generated arousal, take three deep breaths, and then use words to negotiate.

The study to test the effectiveness of the intervention to promote emotion knowledge recruited 177 preschool students and 26 teachers who were involved in a low-income preschool Head Start program in the rural mid-Atlantic states. The Emotions Course and Emotion-Based Prevention Program were delivered in three parts:

- A two-hour workshop before the semester began to help teachers learn how to teach the Emotions Course in their classroom

- Biweekly observation of the teacher’s classroom by a member from the research team to provide a post-class consultation to refine and improve the teacher’s delivery of the Emotions Course and Emotion-Based Prevention Program

- Monthly meetings between parents and researchers to discuss the Emotions Course content and its instructional strategies. In these meetings, parents discussed teachers’ instructional techniques to help children understand, regulate, and utilize basic emotions.

The validity and effectiveness of the intervention program were assessed in three ways, and all the measures were scored the week before the intervention began and again at the end of the intervention.

- The children took an emotion knowledge test where they viewed a photograph of a facial expression and identified the emotion.

- Teachers rated the children on both emotion knowledge and frequency of expressing positive emotions like interest and joy during class.

- Trained raters objectively scored the frequency with which each child displayed negative emotional episodes during class.

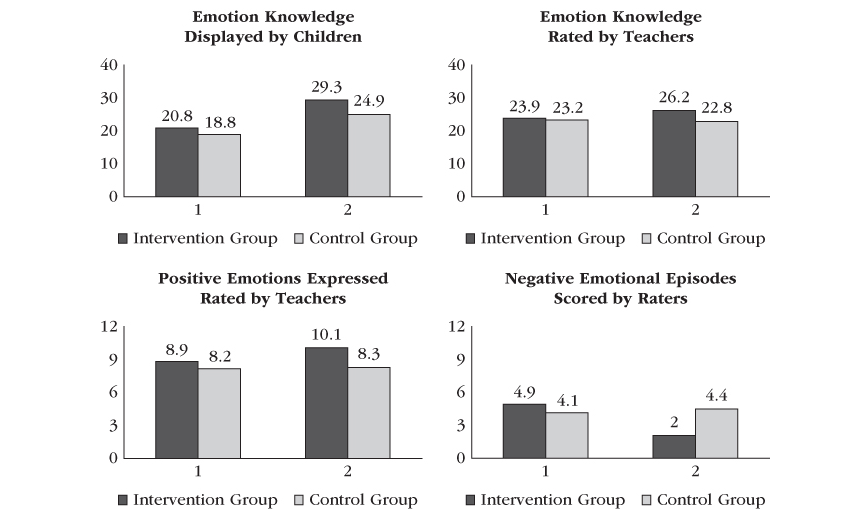

Results from the 20-week Emotions Course and Emotion-Based Prevention Program showed that the intervention produced its intended effect and produced positive benefits.

- Teachers rated that the children in the experimental group expressed positive emotions significantly more frequently after 20 weeks.

- Raters scored the children in the same group as displaying a considerably lower number of negative emotional episodes over the same period.

- Teachers rated children in their class as displaying fewer post-intervention negative emotions and more post-intervention social competence.

- Parents rated the children in the experimental group as displaying less post-intervention aggressive behavior and less post-intervention depressive behavior at home than parents of children in the control group.

Overall, this intervention was a success story because it showed that children could increase their emotion knowledge, and, when they do, they increase their capacity for effective emotion regulation.

A Take-Home Message

One reason why the study of motivation matters is because researchers have been able to design and implement successful interventions to improve lives, for students as well as their teachers and parents.

Many of the studies discussed in this article showed that students who sensed more teacher support for autonomy felt more competent and less anxious, reported more interest and enjoyment in their work, and produced higher quality work.

By providing lessons that offer choice, are connected to students’ goals, and provide both challenges and opportunities for success that are appropriate to students’ level of skill, teachers were able to foster a positive learning environment and positive teacher–student relationships.

I am still learning.

Michelangelo

Tell us about your favorite way to motivate students or share a story of what motivates you if you’re still learning.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview.

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

- Bauer, K. N., Orvis, K. A., Ely, K., & Surface, E. A. (2016). Re-examination of motivation in learning contexts: Meta-analytically investigating the role type of motivation plays in the prediction of key training outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(1), 33–50.

- Bryant, J., & Zillmann, D. (Eds.). (2002). Media effects: Advances in theory and research (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Moon, I. S. (2012). Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 34(3), 365–396.

- Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Song, Y. G. (2016). A teacher-focused intervention to decrease PE students’ amotivation by increasing need satisfaction and decreasing need frustration. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 38(3), 217–235.

- de Bono, E. (1967). The use of lateral thinking. Penguin Books.

- de Bono, E. (1995). Teach yourself to think. Penguin Books.

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048.

- Ellwood, R., & Abrams, E. (2018). Student’s social interaction in inquiry-based science education: How experiences of flow can increase motivation and achievement. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 13, 395–427.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2014). The history of self-determination theory in psychology and management. In M. Gagné (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory (pp. 1–9). Oxford University Press.

- HemaMalini, P. H., & Washington, A. (2014). Employees’ motivation and valued rewards as a key to effective QWL from the perspective of expectancy theory. TSM Business Review, 2(2), 45–54.

- Ikeda, K., Castel, A. D., & Murayama, K. (2015). Mastery-approach goals eliminate retrieval-induced forgetting: The role of achievement goals in memory inhibition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41, 687–695.

- Izard, C. E., Trentacosta, C. J., King, K. A., & Mostow, A. J. (2004). An emotion-based prevention program for Head Start children. Early Education and Development, 15(4), 407–422.

- Keller, J. M. (1987). Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development, 10(3), 2–10.

- Keller, J. M. (2008). First principles of motivation to learn and e3‐learning. Distance Education, 29(2), 175–185.

- Legault, L., Green-Demers, I., & Pelletier, L. (2006). Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic motivation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 567–582.

- Li, T., & Lynch, R. (2016). The relationship between motivation for learning and academic achievement among basic and advanced level students studying Chinese as a foreign language in years 3 to 6 at Ascot International School in Bangkok, Thailand. Human Sciences Scholar, 8(1).

- Malone, T. W., & Lepper, M. R. (1987). Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. In R. E. Snow & M. J. Farr (Eds.), Aptitude, learning, and instruction volume 3: Cognitive and affective process analyses (pp. 223–253). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- MindSteps. (2011). Motivation checklist. Retrieved from https://mindstepsinc.com/motivation/

- MindSteps. (2011). Reflections on motivation. Retrieved from https://mindstepsinc.com/motivation/

- Murayama, K., & Elliot, A. J. (2011). Achievement motivation and memory: Achievement goals differentially influence immediate and delayed remember-know recognition memory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10), 1339–1348.

- Murayama, K., Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., & vom Hofe, R. (2013). Predicting long-term growth in students’ mathematics achievement: The unique contributions of motivation and cognitive strategies. Child Development, 84(4), 1475–1490.

- Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328–346.

- Pérez-López, D., & M. Contero (2013). Delivering educational multimedia contents through an augmented reality application: A case study on its impact on knowledge acquisition and retention. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(4), 19–28.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67

- Shernoff, D. J., Csíkszentmihályi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 158–176.

- Skinner, E., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effect of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571–581.

- Suttie, J. (2012, April 16). Can schools help students find flow? Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/can_schools_help_students_find_flow

- Tohidi, H., & Jabbari, M. M. (2012). The effects of motivation in education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 820–824.

- Ulstad, S. O., Halvari, H., Sorebo, O., & Deci, E. L. (2016). Motivation, learning strategies, and performance in physical education at secondary school. Advances in Physical Education, 6(1), 27–41.

- Yeager, D. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2013). An implicit theories of personality intervention reduces adolescent aggression in response to victimization and exclusion. Child Development, 84(3), 970–988.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Please, can you help me with the citation of this article. How can I cite it in references and where was it publish?

Hi Alexander,

Thanks for your question.

Please use the reference below when citing this article, thanks 🙂

Souders, B. (2020). Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids. PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved from https://positivepsychology.com/motivation-education/

Kind regards,

-Caroline | Community Manager

This is great! Thank you so much! Could you please share the names of the researchers who did the first intervention? Thanks much in advance!

Hi Gulnora,

Glad you enjoyed the post! These researchers are Sung Hyeon Cheon, Johnmarshall Reeve, Yong-Gwan Song and Ik Soo Moon across the following two papers:

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Song, Y. G. (2016). A teacher-focused intervention to decrease PE students’ amotivation by increasing need satisfaction and decreasing need frustration. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 38(3), 217-235.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Moon, I. S. (2012). Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 34(3), 365-396.

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

wonderful

thank you so much

Excellent!

Thanks,

Carlos

Intrinsic and and extrinsic quotation of Tohidi and Jabbari date are a little odd…I know it is from 2012, but you make a typo there and come as 2021.

I am reading this article today and it is still not being corrected. Make me laugh. 🙂

However, THANKS for the article, it is well covered.

Hi Lucy and Rosario,

Whoops! Thank you for the prompt — this has now been corrected. 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager

One more little typo: When the ARCS model is explained, the reference is “(Keller, 1983)” instead of 1987. It’s correct in the references though. Thanks for the article!

Thanks, LS! I’ve also corrected this.

– Nicole | Community Manager

Excellent concept

It’s nice peace of information for the motivation of our kids