The Science of Improving Motivation at Work

All motivation comes from within, whether it is triggered by rewards or endeavors that enhance our self-image or intrinsically motivating activities that we engage in for no reward other than the enjoyment these activities bring us.

All motivation comes from within, whether it is triggered by rewards or endeavors that enhance our self-image or intrinsically motivating activities that we engage in for no reward other than the enjoyment these activities bring us.

The topic of employee motivation can be quite daunting for managers, leaders, and human resources professionals.

Organizations that provide their members with meaningful, engaging work not only contribute to the growth of their bottom line, but also create a sense of vitality and fulfillment that echoes across their organizational cultures and their employees’ personal lives.

“An organization’s ability to learn, and translate that learning into action rapidly, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

Jack Welch

In the context of work, an understanding of motivation can be applied to improve employee productivity and satisfaction; help set individual and organizational goals; put stress in perspective; and structure jobs so that they offer optimal levels of challenge, control, variety, and collaboration.

This article demystifies motivation in the workplace and presents recent findings in organizational behavior that have been found to contribute positively to practices of improving motivation and work life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Motivation in the Workplace

Motivation in the workplace has been traditionally understood in terms of extrinsic rewards in the form of compensation, benefits, perks, awards, or career progression.

With today’s rapidly evolving knowledge economy, motivation requires more than a stick-and-carrot approach. Research shows that innovation and creativity, crucial to generating new ideas and greater productivity, are often stifled when extrinsic rewards are introduced.

Daniel Pink (2011) explains the tricky aspect of external rewards and argues that they are like drugs, where more frequent doses are needed more often. Rewards can often signal that an activity is undesirable.

Interesting and challenging activities are often rewarding in themselves. Rewards tend to focus and narrow attention and work well only if they enhance the ability to do something intrinsically valuable. Extrinsic motivation is best when used to motivate employees to perform routine and repetitive activities but can be detrimental for creative endeavors.

Anticipating rewards can also impair judgment and cause risk-seeking behavior because it activates dopamine. We don’t notice peripheral and long-term solutions when immediate rewards are offered. Studies have shown that people will often choose the low road when chasing after rewards because addictive behavior is short-term focused, and some may opt for a quick win.

Pink (2011) warns that greatness and nearsightedness are incompatible, and seven deadly flaws of rewards are soon to follow. He found that anticipating rewards often has undesirable consequences and tends to:

- Extinguish intrinsic motivation

- Decrease performance

- Encourage cheating

- Decrease creativity

- Crowd out good behavior

- Become addictive

- Foster short-term thinking

Pink (2011) suggests that we should reward only routine tasks to boost motivation and provide rationale, acknowledge that some activities are boring, and allow people to complete the task their way. When we increase variety and mastery opportunities at work, we increase motivation.

Rewards should be given only after the task is completed, preferably as a surprise, varied in frequency, and alternated between tangible rewards and praise. Providing information and meaningful, specific feedback about the effort (not the person) has also been found to be more effective than material rewards for increasing motivation (Pink, 2011).

Motivation Theories in Organizational Behavior

Of the dozens of theories of motivation, some were developed with workplace productivity in mind.

Of the dozens of theories of motivation, some were developed with workplace productivity in mind.

They have shaped the landscape of our understanding of organizational behavior and our approaches to employee motivation. We discuss a few of the most frequently applied theories of motivation in organizational behavior.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation, also known as dual-factor theory or motivation-hygiene theory, was a result of a study that analyzed responses of 200 accountants and engineers who were asked about their positive and negative feelings about their work. Herzberg (1959) concluded that two major factors influence employee motivation and satisfaction with their jobs:

- Motivator factors, which can motivate employees to work harder and lead to on-the-job satisfaction, including experiences of greater engagement in and enjoyment of the work, feelings of recognition, and a sense of career progression

- Hygiene factors, which can potentially lead to dissatisfaction and a lack of motivation if they are absent, such as adequate compensation, effective company policies, comprehensive benefits, or good relationships with managers and coworkers

Herzberg (1959) maintained that while motivator and hygiene factors both influence motivation, they appeared to work entirely independently of each other. He found that motivator factors increased employee satisfaction and motivation, but the absence of these factors didn’t necessarily cause dissatisfaction.

Likewise, the presence of hygiene factors didn’t appear to increase satisfaction and motivation, but their absence caused an increase in dissatisfaction. It is debatable whether his theory would hold true today outside of blue-collar industries, particularly among younger generations, who may be looking for meaningful work and growth.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory proposed that employees become motivated along a continuum of needs from basic physiological needs to higher level psychological needs for growth and self-actualization. The hierarchy was originally conceptualized into five levels:

- Physiological needs that must be met for a person to survive, such as food, water, and shelter

- Safety needs that include personal and financial security, health, and wellbeing

- Belonging needs for friendships, relationships, and family

- Esteem needs that include feelings of confidence in the self and respect from others

- Self-actualization needs that define the desire to achieve everything we possibly can and realize our full potential

According to the hierarchy of needs, we must be in good health, safe, and secure with meaningful relationships and confidence before we can reach for the realization of our full potential.

For a full discussion of other theories of psychological needs and the importance of need satisfaction, see our article on How to Motivate.

Hawthorne effect

The Hawthorne effect, named after a series of social experiments on the influence of physical conditions on productivity at Western Electric’s factory in Hawthorne, Chicago, in the 1920s and 30s, was first described by Henry Landsberger in 1958 after he noticed some people tended to work harder and perform better when researchers were observing them.

Although the researchers changed many physical conditions throughout the experiments, including lighting, working hours, and breaks, increases in employee productivity were more significant in response to the attention being paid to them, rather than the physical changes themselves.

Today the Hawthorne effect is best understood as a justification for the value of providing employees with specific and meaningful feedback and recognition. It is contradicted by the existence of results-only workplace environments that allow complete autonomy and are focused on performance and deliverables rather than managing employees.

Expectancy theory

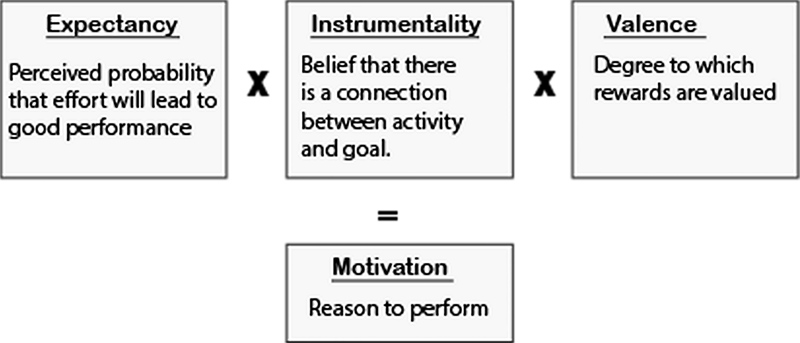

Expectancy theory proposes that we are motivated by our expectations of the outcomes as a result of our behavior and make a decision based on the likelihood of being rewarded for that behavior in a way that we perceive as valuable.

For example, an employee may be more likely to work harder if they have been promised a raise than if they only assumed they might get one.

Expectancy theory posits that three elements affect our behavioral choices:

- Expectancy is the belief that our effort will result in our desired goal and is based on our past experience and influenced by our self-confidence and anticipation of how difficult the goal is to achieve.

- Instrumentality is the belief that we will receive a reward if we meet performance expectations.

- Valence is the value we place on the reward.

Expectancy theory tells us that we are most motivated when we believe that we will receive the desired reward if we hit an achievable and valued target, and least motivated if we do not care for the reward or do not believe that our efforts will result in the reward.

Three-dimensional theory of attribution

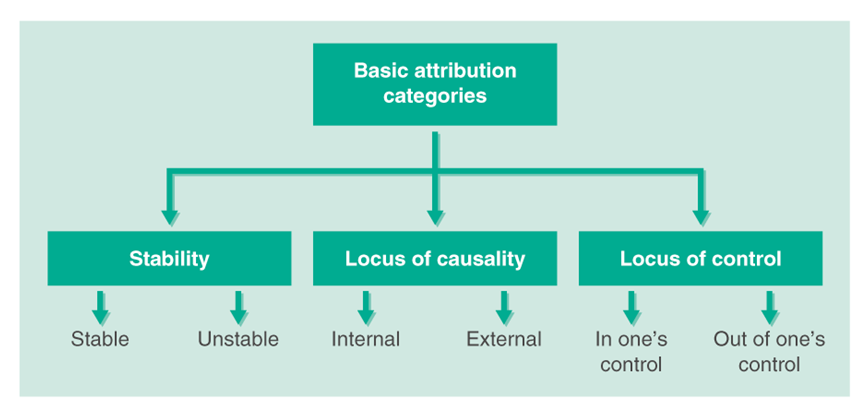

Attribution theory explains how we attach meaning to our own and other people’s behavior and how the characteristics of these attributions can affect future motivation.

Bernard Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution proposes that the nature of the specific attribution, such as bad luck or not working hard enough, is less important than the characteristics of that attribution as perceived and experienced by the individual. According to Weiner, there are three main characteristics of attributions that can influence how we behave in the future:

Stability is related to pervasiveness and permanence; an example of a stable factor is an employee believing that they failed to meet the expectation because of a lack of support or competence. An unstable factor might be not performing well due to illness or a temporary shortage of resources.

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Colin Powell

According to Weiner, stable attributions for successful achievements can be informed by previous positive experiences, such as completing the project on time, and can lead to positive expectations and higher motivation for success in the future. Adverse situations, such as repeated failures to meet the deadline, can lead to stable attributions characterized by a sense of futility and lower expectations in the future.

Locus of control describes a perspective about the event as caused by either an internal or an external factor. For example, if the employee believes it was their fault the project failed, because of an innate quality such as a lack of skills or ability to meet the challenge, they may be less motivated in the future.

If they believe an external factor was to blame, such as an unrealistic deadline or shortage of staff, they may not experience such a drop in motivation.

Controllability defines how controllable or avoidable the situation was. If an employee believes they could have performed better, they may be less motivated to try again in the future than someone who believes that factors outside of their control caused the circumstances surrounding the setback.

Theory X and theory Y

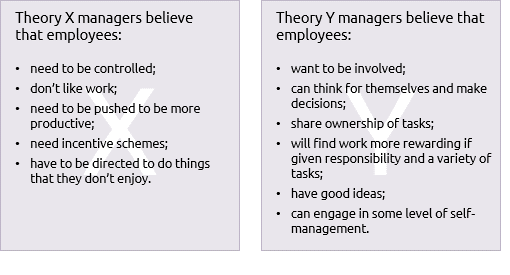

Douglas McGregor proposed two theories to describe managerial views on employee motivation: theory X and theory Y. These views of employee motivation have drastically different implications for management.

He divided leaders into those who believe most employees avoid work and dislike responsibility (theory X managers) and those who say that most employees enjoy work and exert effort when they have control in the workplace (theory Y managers).

To motivate theory X employees, the company needs to push and control their staff through enforcing rules and implementing punishments.

Theory Y employees, on the other hand, are perceived as consciously choosing to be involved in their work. They are self-motivated and can exert self-management, and leaders’ responsibility is to create a supportive environment and develop opportunities for employees to take on responsibility and show creativity.

Theory X is heavily informed by what we know about intrinsic motivation and the role that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays in effective employee motivation.

Theory Z

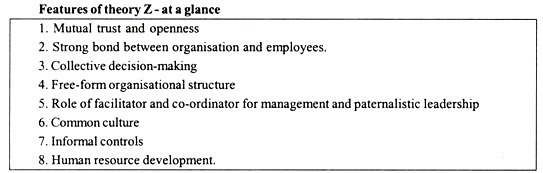

Taking theory X and theory Y as a starting point, theory Z was developed by Dr. William Ouchi. The theory combines American and Japanese management philosophies and focuses on long-term job security, consensual decision making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context.

Its noble goals include increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life, focusing on the employee’s wellbeing, and encouraging group work and social interaction to motivate employees in the workplace.

Employee Motivation Strategies

There are several implications of these numerous theories on ways to motivate employees. They vary with whatever perspectives leadership ascribes to motivation and how that is cascaded down and incorporated into practices, policies, and culture.

The effectiveness of these approaches is further determined by whether individual preferences for motivation are considered. Nevertheless, various motivational theories can guide our focus on aspects of organizational behavior that may require intervening.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory, for example, implies that for the happiest and most productive workforce, companies need to work on improving both motivator and hygiene factors.

The theory suggests that to help motivate employees, the organization must ensure that everyone feels appreciated and supported, is given plenty of specific and meaningful feedback, and has an understanding of and confidence in how they can grow and progress professionally.

To prevent job dissatisfaction, companies must make sure to address hygiene factors by offering employees the best possible working conditions, fair pay, and supportive relationships.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, on the other hand, can be used to transform a business where managers struggle with the abstract concept of self-actualization and tend to focus too much on lower level needs. Chip Conley, the founder of the Joie de Vivre hotel chain and head of hospitality at Airbnb, found one way to address this dilemma by helping his employees understand the meaning of their roles during a staff retreat.

In one exercise, he asked groups of housekeepers to describe themselves and their job responsibilities by giving their group a name that reflects the nature and the purpose of what they were doing. They came up with names such as “The Serenity Sisters,” “The Clutter Busters,” and “The Peace of Mind Police.”

These designations provided a meaningful rationale and gave them a sense that they were doing more than just cleaning, instead “creating a space for a traveler who was far away from home to feel safe and protected” (Pattison, 2010). By showing them the value of their roles, Conley enabled his employees to feel respected and motivated to work harder.

The Hawthorne effect studies and Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution have implications for providing and soliciting regular feedback and praise. Recognizing employees’ efforts and providing specific and constructive feedback in the areas where they can improve can help prevent them from attributing their failures to an innate lack of skills.

Praising employees for improvement or using the correct methodology, even if the ultimate results were not achieved, can encourage them to reframe setbacks as learning opportunities. This can foster an environment of psychological safety that can further contribute to the view that success is controllable by using different strategies and setting achievable goals.

Theories X, Y, and Z show that one of the most impactful ways to build a thriving organization is to craft organizational practices that build autonomy, competence, and belonging. These practices include providing decision-making discretion, sharing information broadly, minimizing incidents of incivility, and offering performance feedback.

Being told what to do is not an effective way to negotiate. Having a sense of autonomy at work fuels vitality and growth and creates environments where employees are more likely to thrive when empowered to make decisions that affect their work.

Feedback satisfies the psychological need for competence. When others value our work, we tend to appreciate it more and work harder. Particularly two-way, open, frequent, and guided feedback creates opportunities for learning.

Frequent and specific feedback helps people know where they stand in terms of their skills, competencies, and performance, and builds feelings of competence and thriving. Immediate, specific, and public praise focusing on effort and behavior and not traits is most effective. Positive feedback energizes employees to seek their full potential.

Lack of appreciation is psychologically exhausting, and studies show that recognition improves health because people experience less stress. In addition to being acknowledged by their manager, peer-to-peer recognition was shown to have a positive impact on the employee experience (Anderson, 2018). Rewarding the team around the person who did well and giving more responsibility to top performers rather than time off also had a positive impact.

Stop trying to motivate your employees – Kerry Goyette

Other approaches to motivation at work include those that focus on meaning and those that stress the importance of creating positive work environments.

Meaningful work is increasingly considered to be a cornerstone of motivation. In some cases, burnout is not caused by too much work, but by too little meaning. For many years, researchers have recognized the motivating potential of task significance and doing work that affects the wellbeing of others.

All too often, employees do work that makes a difference but never have the chance to see or to meet the people affected. Research by Adam Grant (2013) speaks to the power of long-term goals that benefit others and shows how the use of meaning to motivate those who are not likely to climb the ladder can make the job meaningful by broadening perspectives.

Creating an upbeat, positive work environment can also play an essential role in increasing employee motivation and can be accomplished through the following:

- Encouraging teamwork and sharing ideas

- Providing tools and knowledge to perform well

- Eliminating conflict as it arises

- Giving employees the freedom to work independently when appropriate

- Helping employees establish professional goals and objectives and aligning these goals with the individual’s self-esteem

- Making the cause and effect relationship clear by establishing a goal and its reward

- Offering encouragement when workers hit notable milestones

- Celebrating employee achievements and team accomplishments while avoiding comparing one worker’s achievements to those of others

- Offering the incentive of a profit-sharing program and collective goal setting and teamwork

- Soliciting employee input through regular surveys of employee satisfaction

- Providing professional enrichment through providing tuition reimbursement and encouraging employees to pursue additional education and participate in industry organizations, skills workshops, and seminars

- Motivating through curiosity and creating an environment that stimulates employee interest to learn more

- Using cooperation and competition as a form of motivation based on individual preferences

Sometimes, inexperienced leaders will assume that the same factors that motivate one employee, or the leaders themselves, will motivate others too. Some will make the mistake of introducing de-motivating factors into the workplace, such as punishment for mistakes or frequent criticism, but negative reinforcement rarely works and often backfires.

It’s important to keep in mind that motivation is individual, and the degree of success achieved through one single strategy will not be the most effective way to motivate all employees.

Motivation and Job Performance

There are several positive psychology interventions that can be used in the workplace to improve important outcomes, such as reduced job stress and increased motivation, work engagement, and job performance. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted in recent years to verify the effects of these interventions.

Psychological capital interventions

Psychological capital interventions are associated with a variety of work outcomes that include improved job performance, engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Avey, 2014; Luthans & Youssef-Morgan 2017). Psychological capital refers to a psychological state that is malleable and open to development and consists of four major components:

- Self-efficacy and confidence in our ability to succeed at challenging work tasks

- Optimism and positive attributions about the future of our career or company

- Hope and redirecting paths to work goals in the face of obstacles

- Resilience in the workplace and bouncing back from adverse situations (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017)

Job crafting interventions

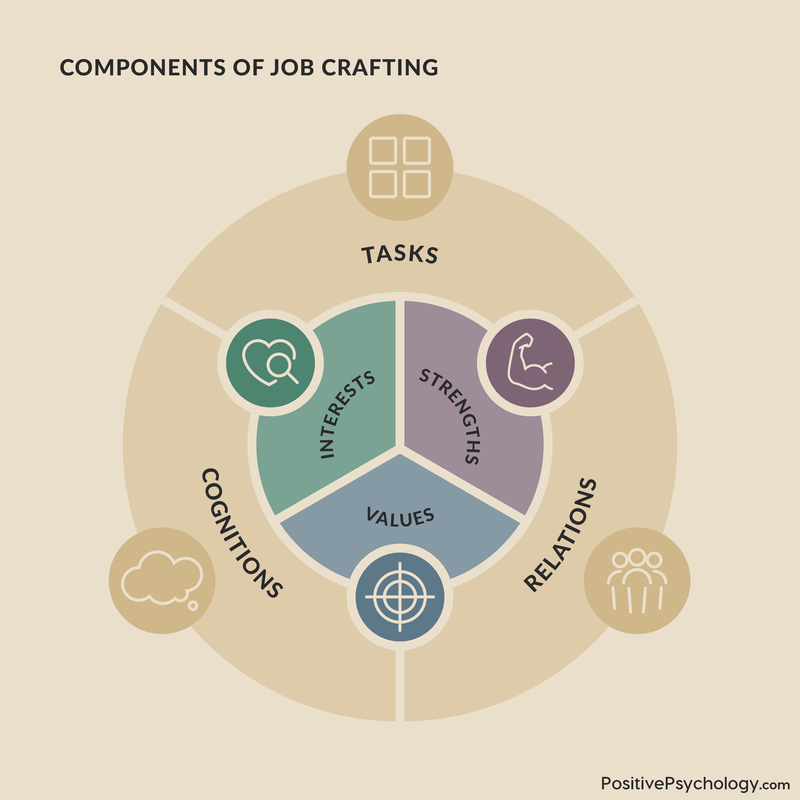

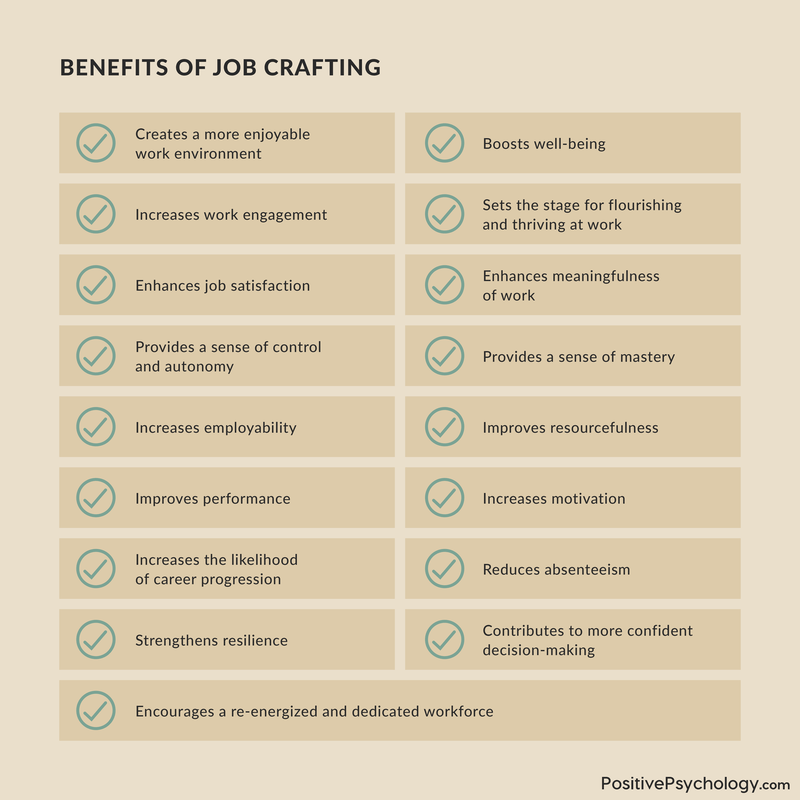

Job crafting interventions – where employees design and have control over the characteristics of their work to create an optimal fit between work demands and their personal strengths – can lead to improved performance and greater work engagement (Bakker, Tims, & Derks, 2012; van Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, 2016).

The concept of job crafting is rooted in the jobs demands–resources theory and suggests that employee motivation, engagement, and performance can be influenced by practices such as (Bakker et al., 2012):

- Attempts to alter social job resources, such as feedback and coaching

- Structural job resources, such as opportunities to develop at work

- Challenging job demands, such as reducing workload and creating new projects

Job crafting is a self-initiated, proactive process by which employees change elements of their jobs to optimize the fit between their job demands and personal needs, abilities, and strengths (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

Leadership and Motivation

Leaders of all sorts can go a long way in increasing employee motivation and engagement at work.

Leaders of all sorts can go a long way in increasing employee motivation and engagement at work.

Today’s motivation research shows that participation is likely to lead to several positive behaviors as long as managers encourage greater engagement, motivation, and productivity while recognizing the importance of rest and work recovery.

One key factor for increasing work engagement is psychological safety (Kahn, 1990). Psychological safety allows an employee or team member to engage in interpersonal risk taking and refers to being able to bring our authentic self to work without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (Edmondson, 1999).

When employees perceive psychological safety, they are less likely to be distracted by negative emotions such as fear, which stems from worrying about controlling perceptions of managers and colleagues.

Dealing with fear also requires intense emotional regulation (Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003), which takes away from the ability to fully immerse ourselves in our work tasks. The presence of psychological safety in the workplace decreases such distractions and allows employees to expend their energy toward being absorbed and attentive to work tasks.

Effective structural features, such as coaching leadership and context support, are some ways managers can initiate psychological safety in the workplace (Hackman, 1987). Leaders’ behavior can significantly influence how employees behave and lead to greater trust (Tyler & Lind, 1992).

Supportive, coaching-oriented, and non-defensive responses to employee concerns and questions can lead to heightened feelings of safety and ensure the presence of vital psychological capital.

Another essential factor for increasing work engagement and motivation is the balance between employees’ job demands and resources.

Job demands can stem from time pressures, physical demands, high priority, and shift work and are not necessarily detrimental. High job demands and high resources can both increase engagement, but it is important that employees perceive that they are in balance, with sufficient resources to deal with their work demands (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010).

Challenging demands can be very motivating, energizing employees to achieve their goals and stimulating their personal growth. Still, they also require that employees be more attentive and absorbed and direct more energy toward their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

Unfortunately, when employees perceive that they do not have enough control to tackle these challenging demands, the same high demands will be experienced as very depleting (Karasek, 1979).

This sense of perceived control can be increased with sufficient resources like managerial and peer support and, like the effects of psychological safety, can ensure that employees are not hindered by distraction that can limit their attention, absorption, and energy.

The job demands–resources occupational stress model suggests that job demands that force employees to be attentive and absorbed can be depleting if not coupled with adequate resources, and shows how sufficient resources allow employees to sustain a positive level of engagement that does not eventually lead to discouragement or burnout (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

And last but not least, another set of factors that are critical for increasing work engagement involves core self-evaluations and self-concept (Judge & Bono, 2001). Efficacy, self-esteem, locus of control, identity, and perceived social impact may be critical drivers of an individual’s psychological availability, as evident in the attention, absorption, and energy directed toward their work.

Self-esteem and efficacy are enhanced by increasing employees’ general confidence in their abilities, which in turn assists in making them feel secure about themselves and, therefore, more motivated and engaged in their work (Crawford et al., 2010).

Social impact, in particular, has become increasingly important in the growing tendency for employees to seek out meaningful work. One such example is the MBA Oath created by 25 graduating Harvard business students pledging to lead professional careers marked with integrity and ethics:

The MBA oath

“As a business leader, I recognize my role in society.

My purpose is to lead people and manage resources to create value that no single individual can create alone.

My decisions affect the well-being of individuals inside and outside my enterprise, today and tomorrow. Therefore, I promise that:

- I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society.

- I will understand and uphold, in letter and spirit, the laws and contracts governing my conduct and that of my enterprise.

- I will refrain from corruption, unfair competition, or business practices harmful to society.

- I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise, and I will oppose discrimination and exploitation.

- I will protect the right of future generations to advance their standard of living and enjoy a healthy planet.

- I will report the performance and risks of my enterprise accurately and honestly.

- I will invest in developing myself and others, helping the management profession continue to advance and create sustainable and inclusive prosperity.

In exercising my professional duties according to these principles, I recognize that my behavior must set an example of integrity, eliciting trust, and esteem from those I serve. I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards. This oath, I make freely, and upon my honor.”

Job crafting is the process of personalizing work to better align with one’s strengths, values, and interests (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Any job, at any level can be ‘crafted,’ and a well-crafted job offers more autonomy, deeper engagement and improved overall wellbeing.

There are three types of job crafting:

- Task crafting involves adding or removing tasks, spending more or less time on certain tasks, or redesigning tasks so that they better align with your core strengths (Berg et al., 2013).

- Relational crafting includes building, reframing, and adapting relationships to foster meaningfulness (Berg et al., 2013).

- Cognitive crafting defines how we think about our jobs, including how we perceive tasks and the meaning behind them.

If you would like to guide others through their own unique job crafting journey, our set of Job Crafting Manuals (PDF) offer a ready-made 7-session coaching trajectory.

Motivation and Good Business

Under the right circumstances, positive institutions can enable positive traits, which in turn can enable positive subjective experiences for their employees.

Under the right circumstances, positive institutions can enable positive traits, which in turn can enable positive subjective experiences for their employees.

Prosocial motivation is an important driver behind many individual and collective accomplishments at work.

It is a strong predictor of persistence, performance, and productivity when accompanied by intrinsic motivation. Prosocial motivation was also indicative of more affiliative citizenship behaviors when it was accompanied by motivation toward impression management motivation and was a stronger predictor of job performance when managers were perceived as trustworthy (Ciulla, 2000).

On a day-to-day basis most jobs can’t fill the tall order of making the world better, but particular incidents at work have meaning because you make a valuable contribution or you are able to genuinely help someone in need.

J. B. Ciulla

Prosocial motivation was shown to enhance the creativity of intrinsically motivated employees, the performance of employees with high core self-evaluations, and the performance evaluations of proactive employees. The psychological mechanisms that enable this are the importance placed on task significance, encouraging perspective taking, and fostering social emotions of anticipated guilt and gratitude (Ciulla, 2000).

Some argue that organizations whose products and services contribute to positive human growth are examples of what constitutes good business (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004). Businesses with a soul are those enterprises where employees experience deep engagement and develop greater complexity.

In these unique environments, employees are provided opportunities to do what they do best. In return, their organizations reap the benefits of higher productivity and lower turnover, as well as greater profit, customer satisfaction, and workplace safety. Most importantly, however, the level of engagement, involvement, or degree to which employees are positively stretched contributes to the experience of wellbeing at work (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004).

A Take-Home Message

Daniel Pink (2011) argues that when it comes to motivation, management is the problem, not the solution, as it represents antiquated notions of what motivates people. He claims that even the most sophisticated forms of empowering employees and providing flexibility are no more than civilized forms of control.

He gives an example of companies that fall under the umbrella of what is known as results-only work environments (ROWEs), which allow all their employees to work whenever and wherever they want as long their work gets done.

Valuing results rather than face time can change the cultural definition of a successful worker by challenging the notion that long hours and constant availability signal commitment (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011).

Studies show that ROWEs can increase employees’ control over their work schedule; improve work–life fit; positively affect employees’ sleep duration, energy levels, self-reported health, and exercise; and decrease tobacco and alcohol use (Moen, Kelly, & Lam, 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011).

Perhaps this type of solution sounds overly ambitious, and many traditional working environments are not ready for such drastic changes. Nevertheless, it is hard to ignore the quickly amassing evidence that work environments that offer autonomy, opportunities for growth, and pursuit of meaning are good for our health, our souls, and our society.

Leave us your thoughts on this topic.

Related reading: Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- Anderson, D. (2018, February 22). 11 Surprising statistics about employee recognition [infographic]. Best Practice in Human Resources. Retrieved from https://www.bestpracticeinhr.com/11-surprising-statistics-about-employee-recognition-infographic/

- Avey, J. B. (2014). The left side of psychological capital: New evidence on the antecedents of PsyCap. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(2), 141–149.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (vol. 3). John Wiley and Sons.

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359–1378

- Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 3–52). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104). American Psychological Association.

- Ciulla, J. B. (2000). The working life: The promise and betrayal of modern work. Three Rivers Press.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin Books.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 863), 499–512.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin.

- Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 315–342). Prentice-Hall.

- Herzberg, F. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits – self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308.

- Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 265–290.

- Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited: Management and the worker, its critics, and developments in human relations in industry. Cornell University.

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 339-366.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., & Lam, J. (2013). Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? Journal of occupational health psychology, 18(2), 157.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E., Tranby, E., & Huang, Q. (2011). Changing work, changing health: Can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(4), 404–429.

- Pattison, K. (2010, August 26). Chip Conley took the Maslow pyramid, made it an employee pyramid and saved his company. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/1685009/chip-conley-took-maslow-pyramid-made-it-employee-pyramid-and-saved-his-company

- Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Penguin.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1-9.

- Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 25) (pp. 115–191). Academic Press.

- von Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands–resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(3), 686–701.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Good and helpful study thank you. It will help achieving goals for my clients. Thank you for this information

A lot of data is really given. Validation is correct. The next step is the exchange of knowledge in order to create an optimal model of motivation.

A good article, thank you for sharing. The views and work by the likes of Daniel Pink, Dan Ariely, Barry Schwartz etc have really got me questioning and reflecting on my own views on workplace motivation. There are far too many organisations and leaders who continue to rely on hedonic principles for motivation (until recently, myself included!!). An excellent book which shares these modern views is ‘Primed to Perform’ by Doshi and McGregor (2015). Based on the earlier work of Deci and Ryan’s self determination theory the book explores the principle of ‘why people work, determines how well they work’. A easy to read and enjoyable book that offers a very practical way of applying in the workplace.

Hi David,

Thanks for mentioning that. Sounds like a good read.

All the best,

Annelé

Motivation – a piece of art every manager should obtain and remember by heart and continue to embrace.

Exceptionally good write-up on the subject applicable for personal and professional betterment. Simplified theorem appeals to think and learn at least one thing that means an inspiration to the reader. I appreciate your efforts through this contributive work.

Excelente artículo sobre motivación. Me inspira. Gracias

Very helpful for everyone studying motivation right now! It’s brilliant the way it’s witten and also brought to the reader. Thank you.

Such a brilliant piece! A super coverage of existing theories clearly written. It serves as an excellent overview (or reminder for those of us who once knew the older stuff by heart!) Thank you!