What is Locke’s Goal Setting Theory of Motivation?

Do you often find yourself struggling to change your habits, regardless of how willing you are to set objectives? If your goals rarely reach fruition, you are not alone.

Do you often find yourself struggling to change your habits, regardless of how willing you are to set objectives? If your goals rarely reach fruition, you are not alone.

For many, there is the ‘you’ who you would like to be, and then (more consistently) the ‘you’ that you are.

These two versions of yourself are not always aligned. If they were, we would all be superheroes.

Disillusionment may follow about the number of things you “could” have done if only you had been persistent in your endeavors.

Research in psychology is here to orientate ourselves in a complex world, and even help us live our lives in more fulfilling and productive ways.

Locke’s goal-setting theory of motivation, which has been tested and supported by hundreds of studies involving thousands of participants, consistently delivers positive changes in the lives of individuals worldwide (Locke and Latham, 2019).

This article will address Locke’s ideas and give you insight into how to benefit from them.

They may play a big role in helping you live your best life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

- What is Goal-Setting Theory? A Look at Edwin Locke’s Theory

- Goal-Setting Research: Findings and Statistics

- Theoretical Definition(s) of Goal-Setting

- Examples of the Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation in Practice

- Key Studies Related to Goal-Setting Theory

- Self-Efficacy and Goal-Setting

- The Goal-Setting Framework

- How is Goal-Setting Related to Behavioral Change?

- Can Goal-Setting Help Decision Making?

- Goal-Setting vs. Expectancy Theory

- 9 Excellent Journal Articles for Further Reading

- A Nuanced Perspective

- 4 PowerPoints about Goal-Setting Theory (PPTs)

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Goal-Setting Theory? A Look at Edwin Locke’s Theory

Does this quote sound familiar? It is vital to modern goal-setting theory, even though it is over 2,500 years old.

When it is obvious that the goals cannot be reached, don’t adjust the goals, adjust the action steps.

Confucius 551-479 B.C.

If you are new to this quote, it may be time to write it down and memorize it.

Most goals are possible to achieve, but people are unsuccessful at goal-setting when they omit to consider the most essential ingredients to any given goal.

Perhaps you made a resolution over a glass of wine on New Year’s Eve, or while you were sitting on the subway coming back from work, determined to maximize your company’s outputs.

You were taken by the belief, then, that you would train for a couple of months before running that summer marathon; that your team-building exercises would strengthen the bonds between your employees and in turn, positively impact their performance at work; that you would write 500 words a day and complete your first novel.

Without a doubt, you have already been exposed to countless inspirational quotes.

As one example, J. K. Rowling has a great inspirational quote. After all, she drafted Harry Potter on the back of a napkin in a cafe in Edinburgh. She believes that:

“everything is possible if you’ve got enough nerve.”

If this quote inspires you, that is fabulous. It is not always enough, however, to read a quote like this and change your goal-driven actions. Even with someone as inspiring as

In 90% of the cases, reading a motivational quote and promising yourself to work harder, change this or that habit, or improve an aspect of your life guarantees failure. Why is this? If setting goals and succeeding is part of what makes ‘human,’ then how do we address this fail-prone tendency?

It matters, to achieve your goals, as working towards meaningful goals provides us with a sense of direction, purpose, and meaning in life.

The more goals we set—within healthy boundaries—the more likely we are to build self-confidence, autonomy, and happiness.

It is time to explore the science behind goal-setting. Let’s flip that 90% failure rate on its head.

Goal-Setting Research: Findings and Statistics

Many studies on goal-setting reveal that the habit of making goals is strong, cross-culturally; however, the rate of attaining those goals via small, manageable changes is weak.

Many studies on goal-setting reveal that the habit of making goals is strong, cross-culturally; however, the rate of attaining those goals via small, manageable changes is weak.

The following findings summarize the last 90 years of goal-setting:

- Cecil Alec Mace conducted the first study on goal-setting in 1935;

- People who write their goals are more likely to achieve their goal than those who don’t by 50%;

- Motivation experts agree that goals should be written down, and carried with oneself, if possible;

- 92% of New Year resolutions fail by the 15th of January;

- Carefully outlined goals, which can be measured and set within specific timeframes, are more effective;

- Explaining your goals to someone you are close to, or making the commitment public, substantially increases your chances of reaching your goal;

- By contrast, goals that are kept to oneself are more likely to be mixed up with the 1,500 thoughts that the average person experiences by the minute;

- Often, achieving a goal means sacrificing something or putting aside certain habits, or beliefs about yourself–it may even result in an emotional or physical toll;

- Harvard research documents that 83% of the population of the United States do not have goals.

- Goal-setting typically yields a success rate of 90%;

- Goals have an energizing function. The higher the goal, the greater the effort invested (Locke & Latham, 2002).

Theoretical Definition(s) of Goal-Setting

To provide context, here are a few definitions of goal-setting defined by experts in the field:

Broadly defined, goal-setting is the process of establishing clear and usable targets, or objectives, for learning.

(Moeller, Theiler, & Wu, 2012)

Goal-setting theory is summarized regarding the effectiveness of specific, difficult goals; the relationship of goals to affect; the mediators of goal effects; the relation of goals to self-efficacy; the moderators of goal effects; and the generality of goal effects across people, tasks, countries, time spans, experimental designs, goal sources (i.e., self-set, set jointly with others, or assigned), and dependent variables.

(Locke & Latham, 2006)

Edwin Locke’s goal-setting theory argues that for goal-setting to be successful with desired outcomes, they must contain the following specific points (Lunenberg & Samaras, 2011):

- Clarity: goals need to be specific;

- Challenging: goals must be difficult yet attainable;

- Goals must be accepted;

- Feedback must be provided on goal attainment;

- Goals are more effective when they are used to evaluate the performance;

- Deadlines improve the effectiveness of goals;

- A learning goal orientation leads to higher performance than a performance goal orientation;

- Group goal-setting is as important as individual goal-setting.

The following video offers a concise explanation that summarizes the actions and steps to achieve specific goals. It’s less than 3 minutes and informative.

This video clarifies—with the help of Chef Alfredo and Boss Romero—what implementing goals with employees looks like, practically speaking. The role of precision is key for employees to fulfill any task.

To make the memorization of these points easier, the acronym SMART may help you recall what the most important attributes of effective goal-setting are:

- Specific;

- Measurable;

- Assignable;

- Realistic;

- Time-based.

How do these work out in practice? In short, the answer relates to specificity, which we will address next.

Examples of the Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation in Practice

Put aside the irresistible need to make your goal as vague and romantic as possible and stick with the raw stuff. What action items do you need to do, to achieve this goal?

The anagram “SMART” is here to assist you in this process.

Getting SMART

The first point of the anagram says that goals should be ‘specific.’ All you need to do is make sure you are clear about what your goal is concretely going to deal with.

For example, instead of saying, “I must become more social” (if say, you are a lonesome cat lady who receives visits once a month), first define what you mean by being social, what your expectations are of social life and the ways in which you feel a greater social presence in your life would enhance it.

Then, sketch out a plan to put into action immediately, tackling instances of daily life you can work on (in the workplace, in already existing relationships, during daily encounters) and the extra incentives you can take to get out of your way to meet new people and enjoy new experiences and activities.

Write down what you are aiming to achieve and what you can do that may positively impact your socializing efforts (e.g. becoming more hospitable, relaxed, caring, kind, compassionate, empathetic).

Alternatively, specificity can also refer to setting specific dates, times, locations at which you will commit to spending time dedicating yourself to your goal.

Next, we need to consider what measurable goals mean.

‘Measurable’ is that you should be able to measure in one way or another whether you have completed your goal or not, or still in the process of doing so.

How your goal should be measured is up to you. Still, you should have a clear idea and expectation as to how your goal, once completed, would look like.

If your goal was to become more social, that could mean to build strong friendships with two new people and to commit to attending one social event every week for an entire year.

Keeping track through ‘measurement’ helps to give you a sense of where you currently find yourself in relation to your goal and where you are heading next.

Goals ought to be ‘acceptable’ to you. That means that you must not only identify with them but also, feel like they are in line with your value system and that they won’t lead you to transgress your sense of integrity in any way.

If the goal is to be more social, the ‘acceptability’ part comes into play at the level of what you feel an adequate friendship would look like.

Whether its sharing fun activities, emotional and intimate conversations, cooking or playing sports together, it’s important to be self-aware, to know what you are after and how your beliefs and feelings are entangled with the goal you are about to set for yourself.

Your goal must be realistic. In other words, you have to work with what you have while pushing yourself slightly beyond in order to change your current reality.

Going back to the instance of the lonesome cat lady (nothing wrong about that), a realistic goal would be to make efforts to develop at least two new friendships over the next six months, and not, say, to become a popular member of the community, as achieving this may take considerably more time.

We have just briefly mentioned the time framework, but nonetheless, it’s totally worth re-emphasizing as much as necessary. The timeframe is all about setting a fixed deadline by which you should have completed your goal.

Regardless of what you have decided to do, make sure you interconnect your goal with your calendar, and that you make the necessary adjustments in your daily life so that working on your goal happens smoothly and gradually.

Key Studies Related to Goal-Setting Theory

Regardless of the tasks involved, the goal source, the setting, or the time frame, it is the tenets of Locke’s goal-setting theory that remain solid.

Regardless of the tasks involved, the goal source, the setting, or the time frame, it is the tenets of Locke’s goal-setting theory that remain solid.

Over time, the SMART theory has proved effective for increasing performance (Latham & Pinder, 2005; Lee & Earley, 1992; Miner, 1984) in a range of settings.

Here are five case studies exploring various ways of goal-setting and its effects.

5 Interesting Case Studies on Goal-Setting Theory

Performance, if set as a goal, does not lead to the same results without the specific goals of gaining knowledge and skillsets.

In our first study, Dweck et al. (1986, 1988, 1988) found that in the classroom, two recurrent personality traits could be observed. Students mainly divided into two categories: those primarily focused on gaining knowledge and skills, and those primarily concerned with their grade and performance in the class.

It was found that the first cohort performed better on taught subjects than the second.

Goal-setting, however, is not only about the decided object of focus. There are, in fact, many determinants that shape the goal-setting and goal completion process.

A second study conducted by Atkinson (1958) highlights how the difficulty of the given task also acts as a factor that hinders or improves performance. The highest level of effort took place when the task was moderately challenging, and the lowest level when the task was either too easy or too hard.

Furthermore, the social dimension which accompanies goal-setting should be considered too, whenever possible.

For example, a major study carried out at Dominican University, listing 267 participants recruited from the business sector (Matthews, 2015) showed that:

- Informants who sent weekly reports to someone they were close to accomplished more than those who had not written their goals down. Those who had written goals outlined with specific ways they intended to meet those goals were as successful as those who just informed their goal intentions to a friend;

- Informants who informed their friends of their goal were able to achieve much more than those who only wrote down action commitments and those who did not at all;

- Overall, those who wrote down their goals accomplished much more than those who had not.

In short, this study provided empirical evidence to support the claim that accountability, commitment, and writing down goals have a major influence on an individual’s commitment towards reaching self-imposed goals.

Goal-setting enables people to stay focused and find meaning in what matters in their lives.

In fact, Boa et al. (2018) claim that goals also provide many people a sense of purpose, as well as a drive to live as actively as possible until their death; this proves especially true in the context of illness.

The researchers conducted a comparative case study of 10 healthcare professionals in a hospice, to practice patient-centered goal-setting.

The results indicated that instead of centering the approach around patients, participants tended to articulate them in relation to what they perceived to be important (problem-solving, alleviating symptoms).

This study by Boa et al. (2018) stressed the importance of making the goals suitable for the priorities of the individual, so as to maximize their effectivity and enhance people’s quality of life.

Another study carried out by Carr (2018) sought to gauge the effects of an already existing goal-setting strategy in an elementary school serving many students from a disadvantaged socio-economic background.

The conclusions pointed out that goal-setting, when implemented consistently, had a positive effect on student self-efficacy, motivation, and reading proficiency.

This, Car argues, happened when the goals being set were specific, measurable, achievable, reasonable, timely and challenging at the same time.

Essentially, the SMART anagram prevails in many situations, backgrounds, and perspectives.

In Defense of Learning Goals

For many, the notion of performance as an accomplishment intertwines with goal-setting.

Just valuing or wanting the “end-product,” and omitting what it takes to get there, is a common mistake made by many.

That’s why research expresses how goals about learning (rather than performance) have higher success rates of goals being met.

The emphasis on learning has a trickle-down effect that actually benefits performance after all. The five studies listed below highlight the difference between performance and knowledge-based goals:

- Winters and Latham (1996) found that setting a learning goal rather than a performance goal for tasks (for individuals with insufficient knowledge) was most effective;

- Similarly, Drach-Zahavy and Erez (2002) made the case that people with a set learning goal for themselves (mentioned in their work as a “strategy goal”) perform better than those who had set a performance-related goal on a task that involved predicting stock-market fluctuations;

- Seijts, Latham, and Tasa (2004) made the point that informants who were assigned a challenging learning goal reached more market share on an interactive, computer-based simulation of the US cellular telephone industry than participants who were assigned a high-performance goal instead;

- Kozlowski and Bell’s study (2006) concluded that assigning a learning goal improved the self-regulatory affective and cognitive mechanisms, in contrast with a goal emphasizing high-performance;

- Last but not least, Cianci, Klein, and Seijts (2010) reported that people who had a learning goal were less prone to tension. They also performed better even after negative feedback, compared to those only assigned a performance goal.

To implement learning-driven goals, it is important to understand how they differ from performance goals.

A performance goal might be something like, “I want to become fluent in XY language,” whereas a learning goal would be:

“by next December, I want to learn how to speak conversational XY language. So, I will be taking several classes on a weekly basis, download the Duolingo app and work at least an hour every day on memorizing a few words in my chosen language. I will also try to get in touch and meet people who speak this language to improve my exposure to it.”

See the difference?

Self-Efficacy and Goal-Setting

Self-efficacy is a concept coined and developed by Albert Bandura. It is a cornerstone concept in the field of positive psychology.

Lightsey (1999) writes that:

“it is difficult to do justice to the immense importance of this research for our theories, our practice, and indeed for human welfare.“

This emphasizes how the construct has had a potent effect on several areas ranging from phobias and depression to vocation choice and managerial organization.

Akhtar (2008) defines self-efficacy as:

“the belief we have in our own abilities, specifically our ability to meet the challenges ahead of us and complete a task successfully.”

The idea that “what we think” affects “what we do” is not new. The field of positive psychology has explored the impact of our beliefs and worldviews on our health and how we live our lives.

As Mahatma Gandhi famously said:

“a man is but a product of his thoughts. What he thinks, he becomes.”

It is important to distinguish a person’s capability with how they perceive their own capability.

Often, there is also a discrepancy between the person’s desire and the capacity, which leads us to self-efficacy. Self-efficacity is a form of self-confidence which embraces an ‘I can handle this’ attitude. It has an empowering effect on the actions of the person in question.

Motivation, on the other hand, refers to a person’s willingness to fulfill a given task, or goal.

Locke’s goal-setting theory aims to encompass both, by formulating goals which not only are in line with a person’s capabilities but also provides the necessary resources so that the person is motivated by the goal while stimulating his or her sense of self-efficacy.

While it is not exactly possible to instill a sense of self-efficacy in a person who disbelieves their capacity to perform well and push themselves beyond what they think they can achieve, setting goals within a positive framework can make a substantial difference.

The Goal-Setting Framework

What is the best approach to adopt when implementing goals?

What is the best approach to adopt when implementing goals?

We have seen, step by step, the way in which they should be structured. But not the general framework in which they should ground themselves for maximized effectiveness.

Depending on how they are framed, goals can have specific effects on a given person’s learning process and performance. They can be framed negatively, by emphasizing how a person should prevent losses and failure at all cost.

A negative goal-setting approach could look like this:

- My goal for next year is to stop myself from gaining any weight at all.

- All employees should aim to not lose more than fifty out of the company’s two hundred and fifty current customers.

- Students whose grades fall below the average will be penalized and given extra homework for the second semester.

This approach tends to be ineffective and degrading. Research shows that punitive strategies often result in anxiety, a lower persistence, and performance, especially in comparison with goals that are set with a positive outlook (Roney, Higgins, & Shah, 1995).

Frese et al. (1991) have developed the concept of “error management,” which intends to reframe errors during the process as opportunities for the individual to learn from.

Framing mistakes and negative feedback with statements such as “Errors are a natural part of the learning process!” and “The more errors you make, the more you learn!” (Heslin, Carson and VandeWalle, 2008) are beneficial.

In short, discouraging fear-based environments encourages people to try again, rather than give up on their goals. This ‘forgiving’ aspect also enables individuals to expect, and not apprehend, failure as part of the growth process.

Goal-setting is not a straight-forward path to success, and it is important to feel like one can “fail” and still aim for their goal, maybe with added specificity.

As such, if framed positively, the previously mentioned goals look more like this:

- This year, I will try to adopt a diet that will enable me to lose weight. My goal is to reach 80kg, and given that I currently weigh 85kg, my goal is to lose 5kg in total. The first diet I try might not be the right one, and I may have to try several before I find one that works, that is, one that enables me to lose weight and with a specific regime that I can stick to at the same time. I will monitor my progress as the months pass and sign up for a gym membership.

- The company strongly values its relationship with its customers. We currently have 250 and our goal for the upcoming year is to keep this number constant. Your role, therefore, will be to ensure that customers are satisfied with our services by diversifying what we offer and the way in which we relate to them. The only way to achieve this is with different approaches and strategies that we can monitor and assess the outcomes of.

- Students whose respective grade have increased by two points will be rewarded with less homework in the second semester. If the grade does not increase two points, the individual efforts of each will be taken into consideration in the final decision of who should be rewarded in the classroom.

Such an approach provides clear guidelines and expectations of a given goal and also trigger positive emotions. Workplaces, schools, and environments with positive goal-setting get to experience the energy, creativity, and motivation of inspiring spaces.

People like a challenge, especially when it seems difficult but possible.

“Our goals can only be reached through a vehicle of a plan, in which we must fervently believe, and upon which we must vigorously act. There is no other route to success.”

Pablo Picasso

As human beings, we may be ambitious and progressive in setting our goals and knowing what we want but lack direction on how to get there.

It seems Picasso had a solution to this dilemma decades ago. Accumulating research supports the notion that goal-setting paves the way for achievement (Latham & Locke, 2006).

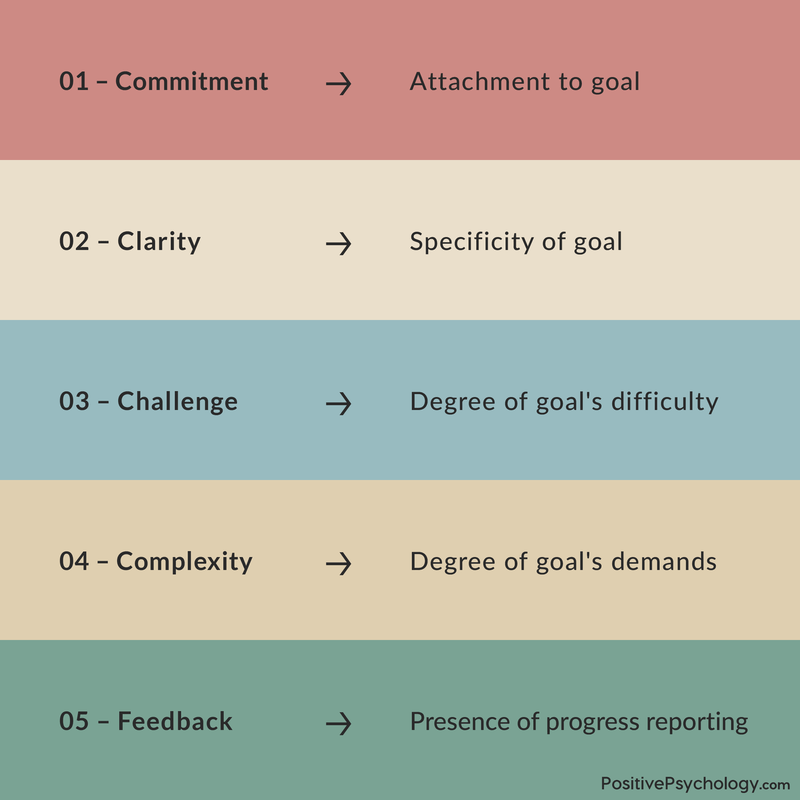

What makes goal-setting successful, though?

- Commitment: Goal performance is strongest when one is committed (Locke & Latham, 1990). The commitment level is, in turn, dependent on our desirability of the goal and our perceived ability to achieve it.

- Clarity: When the goal is clear, precise, unambiguous, and measurable, we know exactly what we want to achieve, increasing our motivation and performance (Avery et al., 1976).

- Challenge: If we know a goal is challenging yet believe it is within our abilities to accomplish it, we are more likely to be motivated to complete a relevant task (Zimmerman et al., 1992).

- Complexity: When tasks for a goal are overly complex, it hinders our morale, productivity, and motivation (Miner, 2005). Keeping the complexity of tasks manageable can increase our chances of success.

- Feedback: Immediate and detailed feedback is important in keeping us on track with our progress towards our goals (Erez, 1977).

So, ensuring that goals are grounded on these principles can pave the way for success. In fact, Latham and Locke (1979) found that effective goal setting can be a more powerful motivator than monetary rewards alone.

How is Goal-Setting Related to Behavioral Change?

So far, we have seen what goals do, but we have omitted to mention what happens to people when they do not set goals in their lives.

Indecision, lack of focus, boredom, and not having something specific to strive for, can lead to a feeling that one is living a dulled, less meaningful version of their life. Symptoms of depression, among other mental health struggles, often appear in these perceived unchanging spaces.

This is because specifically-written goals can provide individuals with a sense of existential structure, purpose, and meaning.

As Locke argues, goals are “immediate regulators of behavior” (Latham, Ganegoda, & Locke, 2011), and they provide the self with a vision for the future and a clear direction to strive towards a specific objective.

More so, goal-directed action coupled with reasoning skills is a fundamental element of what makes us human. Even the “non-human” world thrives with goal-setting parallels.

This is not to say that plants write down their goals in pencil. But let’s have Locke explain how:

“The lowest level of goal-directed action is physiologically controlled (plants). The next level, present in the lower animals, entails conscious self-regulation through sensory-perceptual mechanisms including pleasure and pain. Human beings possess a higher form of consciousness – the capacity to reason. They have the power to conceptualize goals and set long-range purposes”

(Locke, 1969).

The human ability to reflect is a curse and a blessing.

It liberates us from the constraint of the absolute determinism of things but it also means that we are responsible for the choices we make and whether they will contribute to our welfare.

For instance, individuals who start exercising and feeling the numerous health benefits often end up seeing value in making additional lifestyle changes, such as a healthier routine and diet.

Thus, if a goal is perceived by the individual as something that can contribute to their sense of wellbeing or that of the group they are a part of, then it can also serve as a source of inspiration and esteem.

This often leads to a ricochet effect on other behaviors linked to performance and efficacy.

Can Goal-Setting Help Decision-Making?

Goal-setting and decision making are the two voluntary acts that can radically transform a person’s life.

You perhaps have heard the adage, “you cannot save someone who doesn’t want to be saved.”

When it comes to helping others, it is not possible to do so unless they want the help, and also feel enough motivation to take the appropriate steps forward—regardless of how tiring this may prove.

Setting goals empower decision making, and the opposite is true as well. It enables people to filter through what is significant, worth pursuing and what is not.

Goal-Setting vs. Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory was developed by Victor Vroom (1964) and looks at the mental processes which underlie motivation and choice-making.

Expectancy theory was developed by Victor Vroom (1964) and looks at the mental processes which underlie motivation and choice-making.

Vroom outlines three main factors which structure how humans decide to go about their lives and the steps needed to achieve a given result: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

He argues that ‘motivational force’ can be calculated by means of multiplying expectancy with instrumentality and valence.

The actual formula looks like this:

Motivational force = Expectancy x Instrumentality x Valence

Put in a literary way, Vroom’s point is that motivation emerges from a person’s belief that an invested effort will enable them to achieve a certain desired performance, and that the way this performance is played out, will lead to the fulfillment of a specific goal.

In turn, the extent to which the individual perceived this final goal as desirable (valence) will also shape the degree of motivation for the individual to pursue a given goal.

In other words, confidence, assessment of what is required, and the value perceived on the specific outcome equal the energy an individual may feel towards a specific goal.

Expectancy theory adds an interesting dimension to Locke’s goal-setting theory. Locke provides insight into which goals are implemented in effective ways. Vroom, on the other hand, sheds light on how self-esteem, individual perception and the value system of individuals come into play.

The theories coined by Locke and Vroom do intersect in how they emphasize the importance of setting goals that are tailored to subjective needs and capacities.

To spark the necessary ‘motivational force’ for any given challenge, there must be momentum. With this momentum come success, especially when failure is encouraged as part of the learning process.

9 Excellent Journal Articles for Further Reading

One of the great aspects of goal-setting is that it is applicable in most domains of life.

For more detail regarding the different studies mentioned, you can find the original sources in the bibliography. It is possible to find information related to goal-setting on practically every subject.

For example, if you have specific goals to becoming a published writer, there are plenty of step-by-step guides offered on the internet.

There is also a wealth of literature documenting the benefits of goal-setting in the context of workplaces, especially since the theory began as an attempt to enhance employee motivation in the workplace.

For your convenience, we compiled a list of recently published journal articles relating to goal-setting, applied to a range of contexts.

If you don’t have access to academic material and would like to consult on any of the following articles, don’t hesitate to drop us a message.

Goal-setting in the Professional World:

- Exercise Self-Efficacy as a Mediator between Goal-Setting and Physical Activity: Developing the Workplace as a Setting for Promoting Physical Activity by Iwasaki et al. (2017)

- Achievement Goal Orientation and its Implications for Workplace Goal-Setting Programs, Supervisory/Subordinate Relationships and Training by Rysavy (Dissertation, 2015)

- Experiential Exercises on Goal-Setting, Leadership/Followership, and Workplace Readiness (Ritter, 2015)

Goal-setting with Students/Adolescents:

- What is the effect of peer-monitored Fitnessgram testing and personal goal-setting on performance scores with Hispanic middle school students? (Coleman, 2017)

- Effect of Student SMART Goal-Setting in a Low-Performing Middle School (Thomas, 2015)

- Does Participation in Organized Sports Influence School Performance, Mental Health, and/or Long-Term Goal-Setting in Adolescents? (Samarasinghe, Khan, Mccabe, Lee, 2017)

Goal-setting in Healthcare/ with Patients:

- Goal-setting in neurorehabilitation: development of a patient-centered tool with theoretical underpinnings (Aleksandrowicz, 2016)

- Rehabilitation goal-setting: theory, practice, and evidence (Siegert & Levack, 2015)

- Evaluating the Structure of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Survey from the Patient’s Perspective (Fan et al., 2015)

A Nuanced Perspective

Goals, goals, goals.

Staying informed with how to improve oneself and others is important; however, too much absorption with the topic may overlook the very value of existence.

It’s not enough to be busy, so are the ants. The question is, what are we busy about?

Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau’s excellent words invite us to reflect on the broader picture. Do our goals push us to pursue really matters? If so, then continue. If not, perhaps it is time to pause.

Even though goal-setting can indeed strengthen a person’s sense of purpose, self-confidence, and autonomy, the habit of setting goals can lead us astray from our core values.

The current trend, unfortunately, is following this “busy route” where burnout is ingrained with modern corporate culture (Petersen, 2019). It is especially affecting the millennial generation.

As Petersen’s (ibid) article shows, it can be hard enough to perform the most basic tasks, such as answering emails, doing household chores, registering to vote, calling people on their birthdays, etc.

Burnout, Petersen argues, is part of the over-involvement of baby-boomer parents in their children’s lives, as well as the shifting of modern labor relations and social media technologies.

In many ways, this has blurred the line that used to exist between professional and private life, that is largely nonexistent now.

Many people feel pressure to always brand or market who they are or what they do so that they can feel connected and compete for social status, even when not in the professional world. For many, this shows as the internalization of a feeling that one should be working ‘all the time.’

This pushes people to compare their lives or ‘impact’ with others and make goals out of social comparison and insecurity, rather than goals centered from a genuine desire to change something.

A culture of self-care has arisen, as a possible response to burnout and overwhelming times.

Self-care, however, is not a complete solution given that:

“the problem with holistic, all-consuming burnout is that there’s no solution to it. You can’t optimize it to make it end faster. You can’t see it coming like a cold and start taking the burnout-prevention version of Airborne. The best way to treat it is to first acknowledge it for what it is — not a passing ailment, but a chronic disease — and to understand its roots and its parameters.”

Peterson also recalls the words of the social psychologist Devon Price, who, writing on the topic of homelessness, argued that:

“Laziness, at least in the way most of us generally conceive of it, simply does not exist. If a person’s behavior does not make sense to you, it is because you are missing a part of their context. It’s that simple.”

Hence, this comes as a cautionary message against excessive goal-setting and the madness of constant self-development and improvement.

Modern society encourages us to feel that we are never “good enough.” How do we balance the self-compassion that we are enough, with the desire to be better and set goals?

Perhaps one answer is to avoid goals that do not align with your core values, as well as goals that do more harm than good.

On the same note, Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky, and Bazerman (2009) warn about what happens when ‘goals go wild:’ when goals are too narrow, too challenging, too numerous and enacted within an unrealistic timeframe, they can lead to disastrous consequences.

These consequences range from unethical behavior to psychological pitfalls linked with experiencing failure. For example, if a company boss aims to increase profits by over-working and underpaying staff, this is not a sustainable or ethical goal for anyone involved.

The authors, basing on management studies, also reveal how goal-setting may come at the expense of learning. Again, how do we avoid feeding a competitive culture, and instead, promote cultures of growth and intrinsic motivation?

To avoid this, Steve Kerr from General Electric advises managers to refrain from setting goals that are likely to increase their employees’ stress levels or contain punishing failure; instead, Kerr wants to equip staff with the necessary tools to meet the challenging goals.

This approach, Ordonez et al. argue, will encourage managers to consider whether the goal-setting culture benefits the company’s outputs and the wellbeing of their employees.

Locke & Latham (2002) also warned about the potential pitfalls of combining goals with financial rewards in the workplace; this usually brings employers to set rather easy goals as opposed to more challenging ones instead.

Before rushing to set personal or business goals, it is important to consider your motivation.

2 PowerPoints about Goal-Setting Theory (PPTs)

Hopefully, your mind is now buzzing about the ways you could share the value of this content with others. Perhaps this article could inspire your workplace, your classroom, or simply, your lazy and somewhat unmotivated friend.

Reading long articles on the internet is not accessible to everyone since not everyone has the time or interest to invest the effort.

Our role at PositivePsychology.com is to translate and synthesize academic ideas and research into easily accessible writing. Our readers play an essential role in terms of communicating these resources and ideas to the broader public.

Powerpoints can be particularly impactful tools, that can transmit crucial information concisely.

They are therefore the most effective way of getting the message across to a wider audience.

For inspiration, you may want to have a look at these powerpoints that address the topic of goal-setting theory in a range of contexts.

If you are to directly download and make use of any of these, make sure you contact their authors so that they can grant you permission for using their content.

- By Aatmiki Singh

- By John Varghese

A Take-Home Message

We hope to have provided you with an in-depth view of Locke’s goal-setting theory.

Hopefully, after having read this article, you will never go about setting goals in the same way.

Chances are you will be 90% more likely to succeed at them if you put into practice the different points that we have gone through such as specific goals with attainable action items.

Make it about the process of learning, not the end performance.

And remember, stay “SMART.”

What do you think about the balance of goal-setting and also, “being enough?” It is a fine balance. If you have any comments, please add to our comments section below.

We’d love to keep this conversation around goal-setting open to your ideas.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- Akhtar, M. (2008). What is self-efficacy? Bandura’s 4 sources of efficacy beliefs. Positive Psychology UK.

- Atkinson, J. W. (1958). Motives in fantasy, action, and society: A method of assessment and study.

- Avery, C. C., Chase, M. A., Johanson, U. R., & Phillips, L. W. (1976). The Bell System Practices: Linking reward and job design. Personnel Journal, 55(8), 415-420.

- Beal, M. A. (2017). How Does Goal-Setting Impact Intrinsic Motivation And Does It Help Lead To Enhanced Learning At The Kindergarten Level?.

- Boa, S., Duncan, E., Haraldsdottir, E., & Wyke, S. (2018). Patient-centered goal setting in a hospice: a comparative case study of how health practitioners understand and use goal setting in practice. International journal of palliative nursing, 24(3), 115-122.

- Carr, M. (2018). Goal Setting Theory in Action (Doctoral dissertation, Mercer University, Macon, Georgia). Retrieved from https://libraries.mercer.edu/ursa/handle/10898/5130

- Cianci, A. M., Klein, H. J., & Seijts, G. H. (2010). The effect of negative feedback on tension and subsequent performance: The main and interactive effects of goal content and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 618.

- Drach-Zahavy, A., & Erez, M. (2002). Challenge versus threat effects on the goal–performance relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(2), 667-682.

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256.

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040.

- Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of personality and social psychology, 54(1), 5.

- Erez, M. (1977). Feedback: A necessary condition for the goal-setting-performance relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(5), 624-627.

- Frese, M., Brodbeck, F., Heinbokel, T., Mooser, C., Schleiffenbaum, E., & Thiemann, P. (1991). Errors in training computer skills: On the positive function of errors. Human-Computer Interaction, 6(1), 77-93.

- Heslin, P. A., Carson, J. B., & VandeWalle, D. (2008). Practical applications of goal-setting theory to performance management. Performance Management: Putting Research Into Practice, JW Smiter, ed., San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Kozlowski, S. W., & Bell, B. S. (2006). Disentangling achievement orientation and goal-setting: effects on self-regulatory processes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 900.

- Latham, G. P., Ganegoda, D. B., & Locke, E. A. (2011). Goal‐Setting: A State Theory, but Related to Traits. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences, 577-587.

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (1979). Goal setting: A motivational technique that works! Organizational Dynamics, 8(2), 68-80.

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the benefits and overcoming the pitfalls of goal setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332-340.

- Latham, G. P., & Pinder, C. C. (2005). Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 56, 485-516.

- Lee, C., & Earley, P. C. (1992). Comparative peer evaluations of organizational behavior theories. Organization Development Journal.

- Lightsey, R. (1999). Albert Bandura and the exercise of self-efficacy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13(2), 158.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Prentice-Hall.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal-setting theory: A half-century retrospective. Motivation Science.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current directions in psychological science, 15(5), 265-268.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal-setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705.

- Locke, E. A. (1969). What is job satisfaction?. Organizational behavior and human performance, 4(4), 309-336.

- Lunenberg, M., & Samaras, A. P. (2011). Developing a pedagogy for teaching self-study research: Lessons learned across the Atlantic. Teaching and teacher education, 27(5), 841-850.

- Matthews, G. (2015). The study focuses on strategies for achieving goals, resolutions.

- Miner, J. B. (1984). The validity and usefulness of theories in emerging organizational science. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 296-306.

- Miner, J. B. (2005). Organizational behavior 1: Essential theories of motivation and leadership. M. E. Sharpe.

- Moeller, A. J., Theiler, J. M., & Wu, C. (2012). Goal-setting and student achievement: A longitudinal study. The Modern Language Journal, 96(2), 153-169.

- Petersen, A. (2019). How Millennials Became The Burnout Generation. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/annehelenpetersen/millennials-burnout-generation-debt-work

- Ordóñez, L. D., Schweitzer, M. E., Galinsky, A. D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2009). Goals gone wild: The systematic side effects of overprescribing goal-setting. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(1), 6-16.

- Roney, C. J., Higgins, E. T., & Shah, J. (1995). Goals and framing: How the outcome focus influences motivation and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(11), 1151-1160.

- Seijts, G. H., Latham, G. P., Tasa, K., & Latham, B. W. (2004). Goal-setting and goal orientation: An integration of two different yet related literatures. Academy of management journal, 47(2), 227-239.

- Shearer, B. A., Carr, D. A., & Vogt, M. (2018). Reading specialists and literacy coaches in the real world. Waveland Press.

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation (Vol. 54). New York: Wiley.

- Winters, D., & Latham, G. P. (1996). The effect of learning versus outcome goals on a simple versus a complex task. Group & Organization Management, 21(2), 236-250.

- Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663-676.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

BTW the A in SMART is Assignable… Not achievable.

Achievable and Realistic are the same.

Hi,

This was wonderful. Reading this article was enjoyable with full understanding. I didn’t know what to do but I have got a full concept on goal-setting of which i am ready to write about it . Thank you so much.

Great article – I’ve just read it as I am composing my own article on goal setting. There is a lot of really useful information on here and you have managed to condense a lot of information into key messages. The nuanced point really resonated, I am writing about exactly that topic. I have a site which is to help people with self-development and overall well-being and I myself have to work out how to get the balance right between self-development and savouring life/living in the present so it’s good to see it also mentioned here. I will link to this article on my site and bring through some of the key messages to reinforce some of my own.

Great article! So much detail, knowledge, and inspiration in this article. Enjoyed reading it!