The 5 Founding Fathers and A History of Positive Psychology

The shift toward the investigation of optimal human functioning was built on the foundations of humanistic psychology to counter the then dominance of psychopathology and establish a science of human flourishing.

This article explains the history of positive psychology in the context of different waves of modern psychology from the 19th century to the present. The work of the five founding fathers of positive psychology is discussed, and other key influencers of positive psychology are introduced.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

The History of Positive Psychology

The roots of positive psychology stretch back to the ancient Greeks and Aristotle’s concern with eudaimonia (often translated from Greek as happiness), intellectual and moral virtues, and the good life. Also, some of the core elements of positive psychology such as mindfulness, have roots in ancient Eastern spiritual practices.

However, this article will focus on the origins of positive psychology in modern psychology, which emerged as a science during the late nineteenth century from roots in the philosophy of mind.

Originally, psychology developed from the investigation of the functions of the brain, neurological system, cognition, and behavior and their role in the causation and mitigation of psychopathology and mental illness. This is often referred to as the disease model.

Many of the twentieth-century psychological treatments for mental health problems had roots in the treatment of traumatic psychological injury of military personnel following the First and Second World Wars (Pols & Oak, 2007). Yet some psychologists became concerned about these treatment modalities, which required the therapist to act as an aloof expert, rather than conveying empathy and compassion for their patient.

During the 1950s and 60s humanistic psychology developed in response to what the pioneers saw as the reductionist, positivist view of the mind as a complex mechanism likened to a machine- a stimulus-response mechanism in behaviorism or an economy of sexual and aggressive drives in psychoanalysis (Mahoney, 1984).

Humanistic psychology championed the holistic study of persons as bio-psycho-social beings. Abraham Maslow first coined the term “positive psychology” in his 1954 book “Motivation and Personality.” He proposed that psychology’s preoccupation with disorder and dysfunction lacked an accurate understanding of human potential (Maslow, 1954).

The branch of psychology termed positive psychology was championed by Martin Seligman in 1998 when he served as President of the American Psychological Society. The explicit goal was to further investigate human potential to counter the dominance of psychopathology and establish a science of human flourishing (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

The Waves of Psychology

Rather like real ocean waves, some of these waves in psychology emerged almost simultaneously, and merged to form larger, broader trends that have led to what is called positive psychology today.

Introspection

Psychology first emerged as a distinct discipline involved with the science of mind and behavior when Wilhelm Wundt established the first experimental psychology laboratory in Germany in 1879 (Kim, 2016). Meanwhile, William James had established a psychology lab at Harvard in the United States a few years earlier, but he used it for teaching rather than scientific research (Goodman, 2022).

Wundt is associated with structuralism as the earliest school of psychological thought, while James is associated with functionalism. Structuralism was concerned with investigating the functions of the mind through introspection on the tiniest elements of perception. However, James emphasized the significance of the environment in shaping behavior, and preferred a more holistic perspective (Goodman, 2022).

Psychoanalysis

A decade or so later, in the 1890s, Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud established psychoanalysis while treating female patients presenting with the psychosomatic symptoms of ‘hysteria’ (Breuer & Freud, 1895/2004).

A series of experimental interventions led him to develop the techniques of free association and interpreting dreams he described as the royal road to the unconscious (Freud, 1900/1997).

Freud explained how the unconscious functioned as a repository of repressed sexual and aggressive impulses which he later termed “drives”. The aim of psychoanalysis was to sublimate these drives successfully and transform hysterical misery into ordinary unhappiness (Breuer & Freud, 1895/2004).

Psychoanalysis and its unique account of human development and psychopathology was embraced and developed further by a range of students, including Carl Jung, Albert Adler, Melanie Klein, and Donald Winnicott who went on to establish their own schools of psychoanalytic thought (Fine, 1977).

Behaviorism

Meanwhile, a near parallel development occurred that focused on human behavior to the exclusion of the inner world. In the early 1900s, John Watson (Watson, 1913) proposed that we could understand the human mind as a conditioned stimulus response mechanism, and that there was no need to study internal mental states.

He proposed that behavior was learned and could be unlearned. Behaviorism was established by John Watson (Watson, 1924) and taken up by B. F. Skinner (Skinner, 1953) before evolving into the range of behavioral interventions that remain today.

Although psychoanalysis and behaviorism were diametrically opposed in many respects, both focused almost exclusively on the causes of psychopathology and the therapeutic treatment of various psychological disorders (Mahoney, 1984).

Both positioned the psychologist or psychotherapist as an aloof expert on the patient’s problems, which aroused criticism from the pioneers of humanistic psychology.

Humanistic Psychology

Using the metaphor of multiple waves merging into a bigger wave as they roll to the shore (as described above), the next big wave in psychology evolved from three key developments rooted in objections to the reductionist investigation of the human mind and behavior embraced by behaviorism and psychoanalysis.

– Holism

In the 1930s, Germany Max Wertheimer’s Gestalt psychology proposed a macroscopic holistic understanding of human psychology (Wertheimer, 1938). His work was a primary influence on Abraham Maslow from the 1950s onwards whose work is explored below.

– Person-Centeredness

Together with Gestalt therapist Fritz Perls, Maslow founded the Esalen Institute for the study of human potential to conduct investigations outside of the confines of the conventional university setting. The Esalen Institute helped lay the ground for a new person-centered approach to psychology, counseling, and psychotherapy (O’Hara, 1991).

– Meaning Making

Meanwhile, the existential psychology of Rollo May and Viktor Frankl was emerging throughout the 1950s and 60s with a focus on meaning-making as the psychological foundation of mental health (Frankl, 1946/1992; May, 1953).

Holistic, person-centered, meaning-making merged into what Maslow termed ‘the third force’ of psychology (after psychoanalysis and behaviorism): humanistic psychology.

Carl Rogers was a well-known pioneer in the field with his person-centered approach to counseling and psychotherapy. Rogers formulated some of the key concepts fundamental to positive psychology, including what he termed the three core conditions (Rogers, 1957) for effective counseling and psychotherapy:

- Congruence (which conveys authenticity)

- Unconditional positive regard (which conveys acceptance)

- Empathy (which conveys emotional attunement).

Humanistic psychology also embraced transpersonal elements to further the holistic understanding of the human mind and behavior. The founder of psychosynthesis Roberto Assagioli (Assagioli, 1965) regarded each person as a unique combination of personal and transpersonal elements in need of integration. Transpersonal elements connect the person to a sense of something greater which can be expressed

“… in terms of the planet, our ecological footprint, community, our contribution to something of meaning or our interconnectedness with all things”

(The Institute of Psychosynthesis, n.d., para. 3).

The rapid development of the human potential movement shifted the focus of psychology away from psychopathology toward a holistic investigation of optimal human functioning. However, the study of human flourishing was finally championed by positive psychology at the end of the twentieth century (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

Positive Psychology

Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi are widely regarded as the co-founders of positive psychology and the scientific study of human flourishing. The next section outlines the conceptual lineage of positive psychology with a brief description of the work of the five founding fathers.

5 Founding Fathers of Positive Psychology

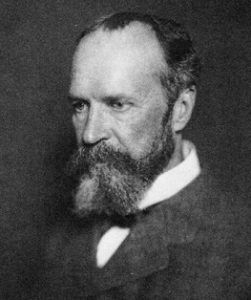

1. William James

He was concerned about why some people seemed able to thrive and overcome adversity, while others developed mental health problems. He argued that understanding subjective experience is key to the investigation of optimal human functioning.

He combined pragmatic and functionalist perspectives to link mind and body and investigate the objective and observable features of inner experience. Many consider James to be America’s first positive psychologist (Froh, 2004) because of his interest in whole person functioning and the full range of subjective experience beyond the confines of psychopathology (Froh, 2004).

You can learn more about James in the video below.

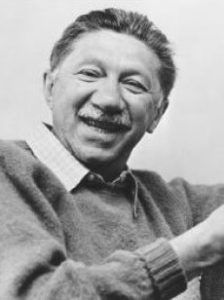

2. Abraham Maslow

In fact, the term “positive psychology” was first coined by Maslow, in his book “Motivation and Personality” (Maslow, 1954). Maslow disliked psychology’s preoccupation with disorder and dysfunction, arguing that it lacked an accurate understanding of human potential.

Maslow argued that while the former psychological approaches of psychoanalysis and behaviorism revealed much about human shortcomings and mental health problems, they neglected to investigate human virtues and aspirations (Maslow, 1954).

This short video by the Academy of Ideas describes the development of Maslow’s thoughts and his study of self-actualization.

3. Martin Seligman

In 1996, Seligman was elected President of the American Psychological Association when he chose to focus on the central theme of positive psychology.

His core proposal was that mental health consisted of more than just the absence of illness and ushered in a new era that investigated the sources of human happiness and fulfillment (University of Pennsylvania, 2022).

His initial investigation into learned helplessness and pessimistic attitudes garnered his initial interest in learned optimism. This led to his work with Christopher Peterson (mentioned below) which aimed to create a positive alternative to the classification of psychopathology in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

During their research, they examined different cultures throughout history, from the ancient Greeks to the present day, to create a list of virtues that are highly valued. This classification system formed the backbone of their book Character Strengths and Virtues (Seligman & Peterson, 2004) and included the following six categories:

- wisdom/knowledge

- courage

- transcendence

- justice

- humanity

- temperance

Professor Seligman is widely celebrated as the founder of the discipline of positive psychology and became Director of the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania in 2004. To date, he has written over 350 scholarly articles and over 30 books in the field. You can hear him explain the origins of his thought and work in this TED Talk below.

4. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

His father was appointed the Hungarian Ambassador to Rome, but when Hungary became communist in 1949 resigned from his position and opened a restaurant. The regime responded by stripping the family of their Hungarian citizenship, and the young Mihaly dropped out of school to work in the family business (Nuszpl, 2018).

Following these adverse experiences, Csikszentmihalyi developed an interest in psychology after seeing Carl Jung give a talk in Switzerland on the traumatized psyches of European people following the Second World War. His interest led him to migrate to study psychology in the USA. The University of Chicago awarded him his PhD in 1965 where he became a professor in 1969.

Csikszentmihalyi had a love of painting, noting that the act of creating was sometimes more important than the finished work itself. This led to his fascination with what he called the flow state. He made it his life’s work to scientifically investigate the different ways of achieving flow as an expression of optimal human experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Csikszentmihalyi’s studies gained much popular interest and have been applied widely to the study of creativity, productivity, and happiness at both an individual and organizational level.

Martin Seligman collaborated with Csikszentmihalyi as a pioneering researcher in positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) and today Csikszentmihalyi is considered one of the founding fathers. You can hear him explain the origins of his ideas and work in this TED Talk below.

5. Christopher Peterson

He was the co-author of Character Strengths and Virtues with Martin Seligman (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and is noted for his work in the study of strengths, virtues, optimism, hope, character, and wellbeing.

Also seen as one of the founding fathers, you can hear him explain the origins of his work in this video below.

6 Other Influencers

The following psychologists deserve a special mention as key influencers on positive psychology, even though they may not be counted among the five founding fathers.

However, there are so many whose work is shaping the future of positive psychology that they can’t all be mentioned in this article.

1. Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura’s self-efficacy theory originated from his social-cognitive theory. It refers to a person’s perception of their ability to achieve their goals by performing the tasks required (Bandura, 1994).

Understanding self-efficacy has been of great importance to positive psychology.

2. Donald Clifton

Clifton followed a similar path to Seligman when he developed strengths-based psychology (Clifton & Harter, 2019). Clifton studied successful individuals to understand how they achieved optimal performance in the workplace.

His research has provided employees with guidance about how to find a fulfilling career suited to their particular strengths. The American Psychological Association honored him in 2002 with a Presidential Commendation as the father of strengths-based psychology (n.d., Gallup).

3. Deci and Ryan

Self-determination theory was developed by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan during the 1980s (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Deci was a professor in the Department of Clinical and Social Sciences at the University of Rochester, New York, and Ryan was a clinical psychologist and Professor at the Institute for Positive Psychology and Education at the Australian Catholic University in Sydney, Australia.

Their ground-breaking work on self-determination updated the hierarchy of needs originally identified by Abraham Maslow. They discovered that human motivation is driven by three components: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2008). This has wide applications in the positive psychology field.

4. Ed Diener

Ed Diener, aka “Dr. Happiness”, is a leading researcher who coined the term subjective wellbeing as a scientifically measurable aspect of human happiness. His research found that there is a strong genetic component to happiness and has led to many studies of the internal and external conditions required to develop it (Diener, 2009).

Diener has also researched the relationship between income and wellbeing, and cultural influences on wellbeing. He has worked with Martin Seligman (Diener & Seligman, 2002) and is a senior scientist for Gallup.

5. Carol Dweck

Carol Dweck conducted research on the notion of the growth versus the fixed mindset. Her research (Dweck, 2017) has been applied to studies of parenting, teamwork, and business leaders. It is a positive psychology tool that is used widely in organizational and educational settings.

6. Barbara Fredrickson

Barbara Fredrickson made her first contribution to positive psychology with her broaden and build theory, which proposes that positive emotions broaden people’s minds and help develop the resources required for resilience during times of adversity (Fredrickson, 2004).

Fredrickson currently acts as the Director of the Positive Emotions and Psychophysiology Laboratory, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

A Take-Home Message

It has taken a lot of organization to write this article in the space available, but we hope that it’s provided you with a useful (if somewhat brief) history of positive psychology since modern psychology became established during the late nineteenth century.

Positive psychology has been built on solid theoretical and evidence-based foundations to establish the strengths-based scientific study of human flourishing that is still growing today.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

Ed: Updated December 2022

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Assagioli, R. (1965). Psychosynthesis: A collection of basic writings. The Viking Press.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In R. J. Corsini (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 3, 368-369). Wiley.

- Breuer, J. & Freud, S. (2004). Studies on hysteria. Penguin. Original work published 1895.

- Clifton, J., & Harter, J. (2019). It’s the manager: Moving from boss to coach. Gallup Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row Publishers.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985) Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior.

Springer. - Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-Determination Theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49, 182-185.

- Diener, E. (2009). Assessing wellbeing. The collected works of Ed Diener. Springer.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84.

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). Mindset. Robinson.

- Fine, R. (1977) The history of psychoanalysis. Jason Aronson.

- Frankl, V. E. (1992). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy (4th ed.) (I. Lasch, Trans.). Beacon Press. Original work published 1946.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1377.

- Freud, S. (1997). Interpretation of dreams. Wordsworth Editions. Original work published 1900.

- Froh, J. J. (2004). The history of positive psychology: Truth be told. NYS Psychologist, 16(3), 18–20.

- Gallup (n.d.) The history of CliftonStrengths. Accessed on Dec 08, 2022 from https://www.gallup.com/cliftonstrengths/en/253754/history-cliftonstrengths.aspx

- Goodman, R. (2022). William James. In Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (Eds.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed on Dec 08, 2022 from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/james/

- Kim, A. (2016) Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt. In Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (Eds.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed on Dec 08, 2022 from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2016/entries/wilhelm-wundt/

- Mahoney, M. J. (1984). Psychoanalysis and behaviorism. In Arkowitz, H., Messer, S.B. (eds) Psychoanalytic therapy and behavior therapy (pp. 303-325). Springer.

- Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper and Row.

- May, R. (1953). Man’s search for himself. W. W. Norton.

- Nuszpl, J. (2018). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi – A life story with his own words. Leadership & Flow. Global Research Program and Network. Accessed on Dec 08, 2022 from https://flowleadership.org/mihaly-csikszentmihalyi-a-life-story-with-his-own-words/

- O’Hara, M. (1991) What is humanistic psychology? Association of Humanistic Psychology. Accessed on Dec 08, 2022 from https://ahpweb.org/what-is-humanistic-psychology/

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues a handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

- Pols, H. & Oak, S. (2007). War & military mental health: the US psychiatric response in the 20th century. American Journal of Public Health (12), 2132-42.

- Rogers, C. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95-103.

- Seligman, M. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. The American Psychologist (55), 5-14.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. MacMillan.

- The Institute of Psychosynthesis. (n.d.) What is psychosynthesis? Accessed on Dec 08, 2022 from https://www.psychosynthesis.org/about/what-is-psychosynthesis/.

- University of Pennsylvania. (2022). Martin E.P. Seligman. Positive Psychology Center. Accessed on 08/12/2022 from https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/people/martin-ep-seligman

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20, 158–177.

- Watson, J. B. (1924). Behaviorism. People’s Institute.

- Wertheimer, M. (1938). Gestalt psychology. Source Book of Gestalt Psychology. Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Dear readers,

The article has been updated December 2022. Some of the comments regarding the content of the previous article have been left here, as they led to interesting discussions.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

– Annelé | Publisher

You say that the underlying atheism of Satre’s position of absolute freedom to be “dampening”. What do you mean by that?

Hi Stewart,

I think the writer meant that a downside of Satre’s message (that each of us needs to work out our own identity without the support of a deity) will potentially narrow the scope of people who can find relief in this approach to psychological wellness. In other words, a lot of people (particularly those who face existential anxiety) will find they can realize greater well-being by being able to connect their actions to an overarching purpose they believe is chosen for them by God or a higher power.

Indeed, many people realize great transformation in themselves and their psychology once having connected to such a purpose, so sometimes an approach to psychological wellness that connects people to the spiritual domain of life can be valuable.

Hope this answers your question!

– Nicole | Community Manager

If that’s what was meant it’s not very clearly communicated, though I agree that is a potential way to look at it since a very large percentage of the world’s population does identify as religious or spiritual so in that limited sense, maybe lack of belief could be seen as excluding a large swath of the population. On the other hand, if we work on the assumption that religion does, indeed, give people a higher chance of being happy then atheism shouldn’t dampen those religious people since they, by definition as religiously identifying individuals, shouldn’t be affected at all in terms of their happiness since atheism is not a necessary pre-requisite for identification as a humanist or existentialist even. Kiekegaard is one of the original inventors of existentialism and he was a deeply religious man. I will however concede that many atheists do in fact also identify as existentialists.

I also found this remark in an otherwise interesting and thought provoking article a bit suspect. Some might say that although an atheistic worldview could be “dampening ” to some so can the idea of focusing on a future after death for the ultimate source of happiness because that could (not necessarily though) imply not focusing on this present life as an opportunity that must be savoured, enjoyed, and made into meaning since you are waiting for a (most likely mythological in the minds of many and most likely supported by embracing the scientific which the article suggests positive psychology does) a paradise after you die. Notice I don’t claim that belief in the supernatural automatically leads to a dampening outlook, but it can. Some people experience deep deep-seated feelings of crippling religious guilt or are convinced the end of the world is imminent, or are subject to extreme privations due to fanatical religious sects, and some researchers note that “religion has been found to be associated with anxiety (eg., Pressman, Lyons, Larson, & Gartner, 1992, as cited in Lewis & Cruise, 2006), fear of death Pressman et al., as cited in Lewis & Cruise, 2006), and guilt (eg., Hood. 1992, as cited in Lewis & Cruise, 2006) [as well as] those whose religious beliefs are at odds with those around them, such as may not in not wishing to accept an arranged marriage, religion may lead to tension and unhappiness. Indeed, there are examples of some sect members being subected to tyranical disipline. Thus, for some individuals, religion maybe associated with happiness, and for others, unhappiness ” (Lewis & Cruise, 2006)

I find this particular comment as to the “underlying . . . dampening” association with atheism more a reflection of the general misunderstanding of atheism and atheists by people that don’t hold that worldview and perhaps watch too much T.V. and mistake if for real life. Honestly it’s insulting, stereotypical, and not actually supported by empirical findings and research but rather than a boogeyman perspective in many cases. Just as it was wrong for people to paint Jews as monsters that would eat babies during the heights of antisemitism during the height of Nazism in Europe and other continents that took up that sad chapter in human existence so too it is wrong to paint non-believers as incapable of experiencing a profound joy life. (Edgell et al., 2006). We atheists can also exult in being alive, in experiencing life through a lens of wonder, of genuine concern for the well-being of all human beings inclusive of believers, non-believers, and agnostics and the spiritual but not religious people in the middle.

Are there negative, nihilistic, and sad atheists? Absolutely! Are there atheists who have committed atrocities? Absolutely. Does this existence by any definition of reason and actual thorough contemplation of evidence based data support this view as a necessary endgame of adopting (or rather being born with and unable to logical find enough evidence for a that although potentially comforting) an atheistic worldview (White, A., 2006)

Could anyone accuse Carl Sagan of never having experience flow, wonder, and a deep appreciation of having been alive? Did Stephan Hawking live a life wallowing in self pity and negativity and lack the ability to look and life and the universe with a sense of wonder? Have you ever seen a video of Neil Degrasse Tyson where he isn’t smiling and super friendly? The popularly accepted view by many is I think more a result of confirmation bias, not always from a stance of active hostility or motivated attempt to spread anti-atheist sentiment, but more from a much too hasty acceptance of harmful and bigoted stereotypes not to mention a homogenous group of clones. I know several atheists that I personally don’t find particularly pleasant people but many who are joyous, compassionate and full of laughter.

The stereotype of “pessimistic atheist” is no more deserved of respect that of “angry black woman” when used if a black woman justifiably points out that someone is judging her based on her gender and color of skin. It doesn’t make her a person with a natural pessimistic and angry disposition if she is reacting to an instance of gender and racial stereotyping and bias. That is a natural reaction to someone treating her unjustly.

I’m not claiming that religion cannot or does not make many people happy. It clearly does for many, including many dear friends and family members that I know and personally respect. But to stereotype atheists as not being equally capable of happiness is neither fair, objective, or necessarily based on solid research methods (Lewis & Cruise, 2006). There is much more research to be done, with more consistent controls, and a very careful need to not equate correlation with cause. After all research that looks at the world map and compares levels of happiness tend to show that the least religious and most atheistic countries actually correlate with the highest levels of happiness in the world (White, 2006), but I would be committing a huge disservice to wonderful people I know who have found much happiness in religion to assume that it is fully due to lack of religion as there may be several other factors at play, such as economic factors, access to health care and social services, and so on.

I hope you don’t read this as an attack on yourself or on Positive Psychology. I enjoyed your article but would hope you would consider a careful reflection on what seems like a possibly flippant assumption about the logical and necessary consequences of atheism. I also noticed reading many of the comments than in many instances where commenters made suggestions of someone you had overlooked as one of the founding fathers (no founding mothers by any chance?) that you considered their advice and decided to update the article so you seem like a quite reasonable person.

Barber, N. (2012). Are religious people happier? Psychology Today.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-human-beast/201211/are-religious-people-happier

Edgell, P., Gerteis, J., & Hartmann, D. (2006). Atheists As “Other”: Moral boundaries and

cultural membership in American society. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 211-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100203

Lewis, C. A. & Cruise, S. M. (2006). Religion and happiness: Consensus, contradictions, comments and concerns. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 9(3), 213-225. https://eds-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.uwa.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=45&sid=5eb59c36-c97b-4dc6-bb70-7506018a0076%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=20531478&db=sih

White, A. (2006). University of Leicester produces the first-ever ‘world map of happiness’.,

EurekAlert!., https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/918323

Great article and overview of the history. Regarding Frankl, to follow up other comments and your request for some information:

Frankl discovered during his ordeal living through the death camps of World War II that the prisoners who survived were not necessarily the strongest or the biggest or the smartest. He found that the survivors shared in common a sense of meaning in their lives, through four characteristics: positive use of their memory, creative use of their imagination, an orientation to the divine, and an ability to behold beauty in art and nature. He developed Logotherapy, or “therapy based on meaning,” to help patients discover the meaning in their lives. Much of his approach resonates with later positive psychologists (Csik., et al.). Interestingly, as empirical evidence in support of Frankl, Harvard’s ongoing Human Flourishing Project has found that among five domains that could influence happiness (health, financial stability, close social relationships, character/ virtue, and meaning/purpose), the domain that correlates most strongly with happiness is in fact meaning and purpose.

Boom 🙂

Great Article- I was holding my waiting for you to mention some women thought. What about Karen Horney, Mary Main, and other works on attachment?