4 Fascinating Classical Conditioning & Behaviorism Studies

Can you think back to when you were in school and the bell rang for lunch?

Can you think back to when you were in school and the bell rang for lunch?

Did you experience a rumble in your stomach, even before you entered the dining hall and saw any food?

If so, your unconscious behavior was actually a real-life example of classical conditioning.

This article provides historical background and theory into classical conditioning and behaviorism. You will also learn how these theories are applied in today’s society and still hold considerable importance when learning about human behavior.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Classical Conditioning in Psychology History

To understand classical conditioning theory, you first need to understand learning. Learning is the process by which new knowledge, ideas, behaviors, and attitudes are acquired (Rehman, Mahabadi, Sanvictores, & Rehman, 2020). Learning can occur consciously or unconsciously (Rehman et al., 2020).

Classical conditioning is the process by which an automatic, conditioned response and stimuli are paired (McSweeney & Murphy, 2014). There are references in the classical conditioning literature to this being stimulus and response behavior (McSweeney & Murphy, 2014).

A famous work on classical conditioning is that by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, born in 1849. His influence on the study of classical conditioning has been tremendous. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this piece of research (The Nobel Prize, n.d.). Classical conditioning was discovered accidentally and was referred to as ‘Pavlovian conditioning’ (Pavlov, 1927).

In this related article you will find practical classroom examples of Classical Conditioning.

Technical terms

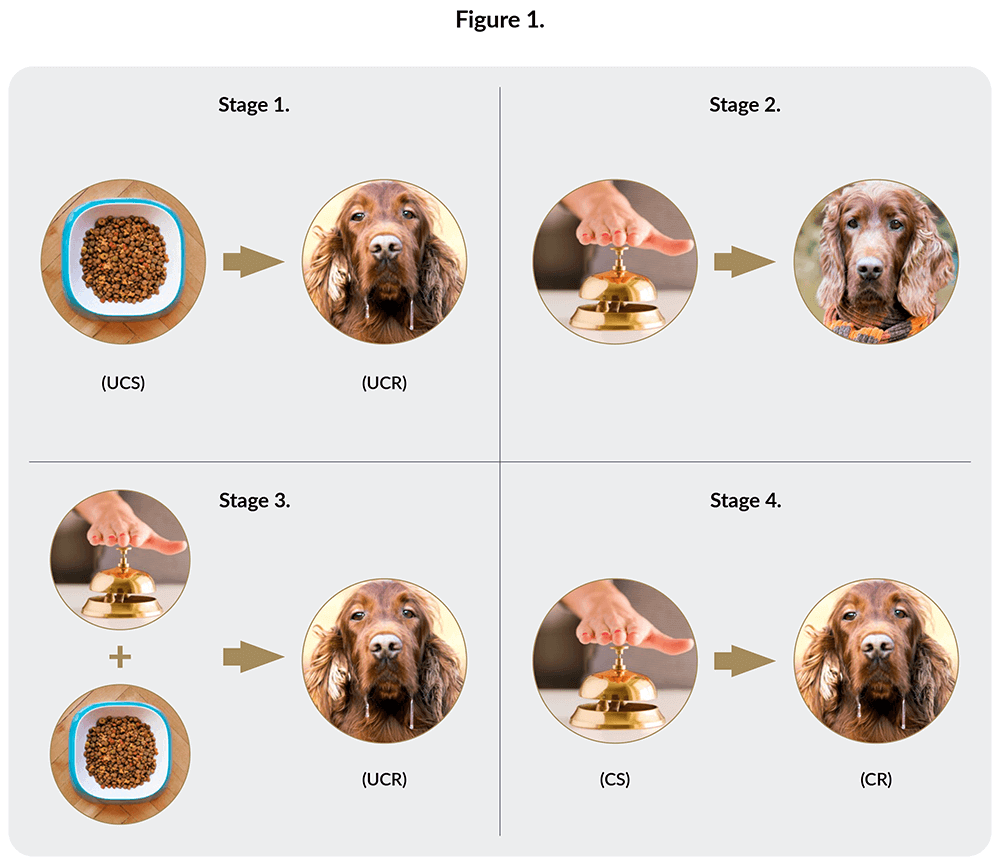

Pavlov (1927) developed the following technical terms to explain the process of classical conditioning and how it works.

- The unconditioned stimulus (UCS) occurs naturally and automatically, and unconditionally triggers a response.

- The unconditioned response (UCR) is the unlearned response. It occurs naturally as a response to the UCS.

- The conditioned stimulus (CS) is a previously neutral stimulus that after being associated with the UCS, results in the triggering of a conditioned response.

- The conditioned response (CR) is a response to the CS being associated with the UCS. The CR is a response that is made to the CS alone and without the UCS being required.

Pavlov’s Dog Experiment Explained

One interesting observation Pavlov made was that just before being given food, the dogs began to salivate. Sometimes this was just from the sight of the lab coats of the technicians feeding them. This made Pavlov wonder why the dogs salivated when there was no food in sight.

Pavlov decided to undertake a series of experiments with the dogs to investigate these observations. Pavlov rang a bell each time, just before feeding the dogs. At first there was no response. Then when the food came out, the dogs realized the sound of the bell meant food, and they salivated. After that, the sound of the bell on its own caused the dogs to salivate. They associated the bell with the arrival of food.

The following diagram (Figure 1) shows the different stages in the classical conditioning process in Pavlov’s (1897) dog experiments.

A Look at the Birth of Behaviorism

Classical conditioning has its roots in behaviorism. Behaviorism measures observable behaviors and events (Watson, 1913; Watson 1924).

John B. Watson, like Pavlov, investigated conditioned neutral stimuli eliciting reflexes in respondent conditioning (Watson & Rayner, 1920). Behaviorism views the environment as the primary influence upon human behavior, not genetic factors (Thorndike, 1905).

Behaviorism derived from the earlier research of Edward Thorndike (1905) and the Law of Effect in the later 19th century. This looked at consequences that strengthen and weaken behavior.

It attempted to replace depth psychology (Vladislav & Didier, 2018), considered having roots in the theories of Sigmund Freud, Carl Gustav, and Alfred Adler (Lewis, 1958). Depth psychology had difficulty testing predictions experimentally (Vladislav & Didier, 2018).

B. F. Skinner, an American psychologist, developed his own stance on the behaviorist approach, known as radical behaviorism (Schneider & Edward, 1987). He suggested that cognitions and emotions have the same variables of control as observed behavior (Mecca, 1974).

His technique was known as operant conditioning. This deals with reinforcement and punishment to increase or decrease the performance of behavior (Skinner, 1953).

Watson’s Little Albert Research

Watson showed that humans can also be conditioned similarly to animals (Beck, Levinson, & Irons, 2009).

Watson used a small infant in his experiments referred to as Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920). The child was exposed to different stimuli, including a rabbit, dog, wool, mask, monkey, and burning newspapers to see his reactions.

Little Albert showed no fear of the objects. It was not until the objects were paired with a loud noise (banging a metal bar with a hammer) that he began to cry after being shown a white rat. The child then expected to hear a frightening noise when he saw the white rat (neutral stimulus) on its own.

The white rat became the conditioned stimulus, and the emotional response of crying became the conditioned response. This is similar to the distress (unconditioned response) he initially displayed to the noise. Further studies showed Little Albert becoming distressed with furry objects and even a Santa Claus mask (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

This very early study in classical conditioning is a perfect example of how phobias may develop (Davey, 1992).

Skinner’s Conditioning Studies

B. F. Skinner (1948) conducted various experiments on rats in a box known as the ‘Skinner Box.’ At first, he put a hungry rat in the box that wandered around and discovered a lever. The rat eventually realized that after it pressed the lever, food was released into the box.

The rat then pressed the lever again each time it was hungry. It then pressed the lever immediately each time it was placed in the box, which showed that it was conditioned. Pressing the lever is the operant response, and the food is the reward (Skinner, 1948).

This type of experiment is also known as instrumental conditioning learning (Ainslie, 1992). The response is instrumental in receiving food. This experiment highlighted positive reinforcement (Skinner, 1948).

Skinner then undertook another experiment with rats. He put the rat in a similar box, and this time an electric current was used. As the rat became distressed and ran around the box, it accidentally knocked the lever. This automatically stopped the electric current.

The rat then learned to head first to the lever to prevent the discomfort of the electric current. Pressing the lever is the operant response, and stopping the electric current is its reward. This experiment highlighted negative reinforcement (Skinner, 1951).

4 Contemporary Findings and Case Studies

Let’s take a look.

1. Classical conditioning and phobias

The classical and operant conditioning models developed by Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner are very relevant in contemporary society today. They can help explain the etiology and treatment of phobias in humans (Davey, 1992).

A phobia is a persistent and irrational fear to a specific situation, object, or activity (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

As an example, consider aerophobia, which is the fear of flying. People who have this phobia have an intense fear and anxiety around flying, sometimes at the mere thought of an airplane.

People with this phobia may avoid flying as much as possible to limit their distress. A closer look at the reason why people develop a fear of flying shows that a bad experience of taking off, terrible weather when flying, or turbulence may have been a crucial factor in the past (Clark & Rock, 2016).

We can think back to Pavlov’s dog experiments to understand more. It seems that the sight or thought of a plane has become the conditioned stimulus, and the fear of flying is the conditioned response.

Effective treatments for a phobia of flying often use the same principles of classical conditioning and learning (Rothbaum, Hodges, Lee, & Price, 2000). Therapists might activate the fear structure by exposing the person to the feared stimuli. This will elicit a fearful response (Rothbaum et al., 2000).

Once the exposure has been undertaken several times, in a process known as habituation (Bouton, 2007), the phobia is no longer reinforced (known as extinction) and eventually disappears (Miltenberger, 2012). In this way, a phobia can be reversed with the same principles of classical conditioning.

2. Classical conditioning and social anxiety

Social anxiety disorder is an anxiety disorder that has characteristics of extreme and persistent social anxiety that causes distress and prevents someone from participating in social activities (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Social anxiety disorder may be triggered by some kind of stressful event early in a child’s life, such as being bullied, family abuse, or some type of public embarrassment (Erwin, Heimberg, Marx, & Franklin, 2006).

The dominant psychological treatment for anxiety disorders also involves repeated exposure, similar to the treatment of phobias described above.

Systematic desensitization is a gradual exposure to the phobic stimulus, perhaps including a gradual exposure to social situations.

Flooding is an alternative approach and not gradual. It is an immediate exposure to the most frightening aspect of the situation (American Psychological Association, n.d.), such as attending a large gathering.

Systematic desensitization and flooding can be undertaken in vitro (imagining exposure to the phobic stimulus) or in vivo (actually exposure to the phobic stimulus). Menzies and Clarke (1993) found that in vivo techniques are much more successful. In vitro can be used if it is more practical.

This is yet another example of how acquired fears can be removed by the principles of classical conditioning.

3. Operant conditioning and gambling

Gambling works based on operant conditioning, as gambling behavior is reinforced, increasing the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated. Gambling can become an addiction and is defined as such in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Griffiths (2009) suggests that some types of gambling, such as slot machines, are addictive because financial rewards can be gained from pulling the lever. He also describes many other rewards, such as physiological rewards (adrenaline rush of winning), psychological rewards (excitement), and social rewards (praise from peers).

Aasved (2003) found that gamblers continued to gamble and repeat these experiences. Gambling is not prone to extinction, as it is reinforced partially (not every time), which makes the gambler repeat the behavior.

Gambling involves only partial reinforcement, as only a portion of responses are reinforced. The lack of predictability keeps people gambling. Does this remind you of Skinner’s study with rats and the rewards of food they gained from pressing the lever?

There are many treatments for gambling addiction. Treatment that combines the principles of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and in vivo strategies of imagining the consequences of gambling behaviors can be effective for problem gamblers (Bowden-George & Jones, 2015).

4. Operant conditioning and substance misuse

Some individuals use alcohol and drugs because of the pleasant positive feelings they gain from the experience. If they compulsively repeat the experience over time to achieve the same rewarding stimuli, the adverse consequence can be addiction (Angres & Bettinardi-Angres, 2008).

Aversion therapy (American Psychological Association, n.d.) is one way of eliminating addictions, through association with noxious and unpleasant experiences (Brewer, Streel, & Skinner, 2017; Platt, 2000). It is based on operant conditioning principles.

Aversion therapy involves pairing the unwanted and addictive behavior with an unpleasant experience. As an example, someone could be administered a medication that causes them to feel nauseous and vomit if they consume alcohol.

After aversion therapy, alcohol may be associated with the feeling of nausea, and so the person does not want to repeat this behavior (Brewer, Meyers, & Johnson, 2000).

Once again, this resembles the technique used by Skinner, when the rats were exposed to an electric shock and learned to press a level to avoid the experience.

What every person can learn from dog training – Noa Szefler

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

Throughout our blog, you’ll find many resources to help your clients address negative habits unconsciously acquired through repeated conditioning.

The tools below can help your clients become more aware of these habits and behaviors and help them gain control over their lives.

- Graded Exposure Worksheet

This worksheet invites clients to rank their phobias from least to most feared as a first step toward conducting an exposure intervention. - Building New Habits

This worksheet succinctly explains how habits are formed and includes a space for clients to craft a plan to develop a new positive habit. - Action Brainstorming

This exercise helps clients identify, evaluate, and then break or change habits that may be getting in the way of making desired changes or moving closer to goals. - Changing Physical Habits

This worksheet helps clients reflect on their vulnerabilities and habits surrounding aspects of their physical health and consider steps to develop healthier habits. - Reward Replacement Worksheet

This worksheet helps clients identify the negative consequences of behaviors they use to reward themselves and select different reward behaviors with positive consequences to replace them.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

A Take-Home Message

Classical and operant conditioning had great significance on the birth of behaviorism.

Classical conditioning has proven to be most valuable in understanding the acquisition of negative and unwanted behaviors such as phobias, anxiety, and addictions.

It is also valuable in providing people with treatment, as the same principles are used to undo inadvertently developed behaviors. These new treatments include exposure therapy, aversion therapy, systematic desensitization, and flooding.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article and will be able to help your own clients make the changes they need with the recommended resources.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Ainslie, G. (1992). Picoeconomics: The strategic interaction of successive motivational states within the person. Harvard University Press.

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Dictionary of psychology.

- Angres, D. H., & Bettinardi-Angres, K. (2008). The disease of addiction: Origins, treatment, and recovery. Disease-A-Month, 54(10), 696–721.

- Aasved, M. (2003). The sociology of gambling (vol. 2). Charles C Thomas.

- Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert. American Psychologist, 64, 605–614.

- Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and behavior: A contemporary synthesis. MA Sinauer.

- Bowden-George, H., & Jones, S. (2015). A clinician’s guide to working with problem gamblers. Routledge.

- Brewer, C., Meyers, R., & Johnson, J. (2000). Does disulfiram help to prevent relapse in alcohol abuse? CNS Drugs, 14, 329–341.

- Brewer, C., Streel, E., & Skinner, M. (2017). Supervised disulfiram’s superior effectiveness in alcoholism treatment: Ethical, methodological, and psychological aspects. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 52(2), 213–219.

- Clark, G. I., & Rock, A. J. (2016). Processes contributing to the maintenance of flying phobia: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 754.

- Davey, G. C. (1992). Classical conditioning and the acquisition of human fears and phobias: A review and synthesis of the literature. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 14(1), 29–66.

- Erwin, B. A., Heimberg, R. G., Marx, B. P., & Franklin, M. E. (2006). Traumatic and socially stressful life events among persons with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20, 896–914.

- Griffiths, M. D. (2009). The psychology of gambling: A personal overview. Psychology Review, 16(1), 25–27.

- Lewis, J. W. (1958). A survey of Adler’s writing. New Scientist, 4(83), 224–225.

- McSweeney, F. K., & Murphy, E. S. (2014). The Wiley Blackwell handbook of operant and classical conditioning. Malden.

- Mecca, C. (1974). Radical behaviorism: The philosophy and the science. Authors Co-operative.

- Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1993). A comparison of in vivo and vicarious exposure in the treatment of childhood water phobia. Behavior Research and Therapy, 31(1), 9–15.

- Miltenberger, R. (2012). Behavior modification, principles and procedures (5th ed.). Wadsworth.

- The Nobel Prize. (n.d.). Retrieved on June 11, 2021, from

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1904/pavlov/facts/ - Pavlov, I. P. (1897). The work of the digestive glands. Griffin.

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Oxford University Press.

- Rehman, I., Mahabadi, N., Sanvictores, T., & Rehman, C. (2020). Classical conditioning. StatPearls. Retrieved June 2, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470326/

- Rothbaum, B. O., Hodges, L. S., Lee, J. H., & Price, L. (2000). A controlled study of virtual reality exposure therapy for the fear of flying. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 1020–1026.

- Skinner, B. F. (1948). ‘Superstition’ in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 168–172.

- Skinner, B. F. (1951). How to teach animals. Freeman.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. MacMillan

- Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology. A. G. Seiler.

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20, 158–177.

- Watson, J. B. (1924). Behaviorism. People’s Institute.

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1–14.

- Vladislav, S., & Didier, G.J. (2018). Dark religion: Fundamentalism from the perspective of Jungian psychology. Chiron.

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)