How to Set Healthy Therapist-Client Relationship Boundaries

Whether or not we’ve thought about it, each of us carries in our heads an implicit set of boundaries that dictate how we expect to be treated in the professional environment.

Whether or not we’ve thought about it, each of us carries in our heads an implicit set of boundaries that dictate how we expect to be treated in the professional environment.

However, in some professions, bringing these expectations to our conscious awareness is critical.

Therapy is one of these professions.

Indeed, understanding and communicating your boundaries as a therapist is essential not only for your own protection, but to ensure you are meeting your legal and ethical obligations to your client.

In this article, we’ll explore the importance of establishing boundaries with your therapy clients, give you strategies to communicate these boundaries, and point you toward a range of useful resources to help you learn more.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Communication Exercises (PDF) for free. These science-based tools will help you and those you work with build better social skills and better connect with others.

This Article Contains:

- Ethical Practices of Psychologists and Coaches

- 6 Ways to Establish Healthy Boundaries With Your Clients

- Communicating Boundaries With Demanding Clients

- A Note on Boundaries With Social Media and Phone Calls

- 4 Helpful Worksheets and Books on the Topic

- A Look at Boundaries With Challenging Clients

- PositivePsychology.com’s Resources

- A Take-Home Message

- References

Ethical Practices of Psychologists and Coaches

Ethics should be at the forefront of one’s mind at all stages of the coaching or therapeutic relationship.

For instance, when considering whether you have the appropriate expertise to help a prospective client, whether a particular form of treatment is suitable, or whether you should refer a client to someone else for additional support, your ethical obligations as a practitioner should factor into your decision.

When considering how to practice ethically as a psychologist, therapist, or coach, you should look to the governing and regulatory bodies for these distinct lines of work, each of which has its own code of ethics.

Examples of such bodies include the American Psychological Association (APA), American Counseling Association, and International Coaching Federation, each of which has a publicly available code of conduct.

Across these codes, you will notice that the discussion of boundary violations revolves around two key violations: boundaries of competence and multiple relationships.

Boundaries of competence

According to the APA’s (2017) code of ethics, therapists should only provide services with populations and in areas of expertise that are within the boundaries of their competence. This competence can stem from the therapist’s education, training, supervised experience, consultation, study, or professional experience.

Likewise, when a professional understanding of an individual’s demographic factors, such as gender identity, language, sexual orientation, or culture, are deemed necessary to provide effective therapy, and the therapist does not possess this, clients should be referred to a professional with the relevant expertise.

Multiple relationships

The APA ethics code (2017) defines multiple relationships taking place when a psychologist is in a professional role with a person and simultaneously engages in or promises to take part in another role with that person or another person closely associated.

Examples of such roles include sexual, social, familial, and business relationships.

The code warns that multiple relationships might impair a psychologist’s objectivity, competence, or effectiveness in performing their functions and might risk exploitation or harm to a client (APA, 2017).

However, best practice guidelines for therapists and coaches do not explicitly rule out all multiple relationships.

Indeed, Zur (n.d.a) notes that multiple relationships are unavoidable in many small and interdependent communities, such as in the military, marginalized communities (e.g., LGBTQ+ and deaf communities), church groups, rural communities, and university campuses.

For example, in an isolated rural community, a therapist may provide psychological services to the family doctor and also seek medical services from that doctor if there is no reasonable alternative.

It is generally advised that therapists should avoid situations involving multiple relationships. However, when such a situation cannot be avoided, they should contemplate their actions in consultation with colleagues and the relevant code of ethics (Barnett & Hynes, 2015).

6 Ways to Establish Healthy Boundaries With Your Clients

Other boundaries may be more malleable or differ between different therapists who use different therapy styles.

Other types of boundaries to consider include the following (Gutheil & Gabbard, 1993):

- Therapist self-disclosure

- Physical touch

- Exchange of gifts

- Fees and modes of payment

- Communication channels

- Length and location of sessions

- Contact outside the therapy room

Establishing clear boundaries serves the therapist and the client, as it helps to create an unambiguous set of ground rules upon which to build trust and guide the behavior of both the client and therapist (Barnett, 2017).

The thoughtful communication of boundaries can also convey the therapist’s commitment to act in the client’s best interest and assurance that they will not intentionally harm the client (Barnett, 2017).

Let’s consider six strategies to establish and communicate healthy boundaries with your therapy clients.

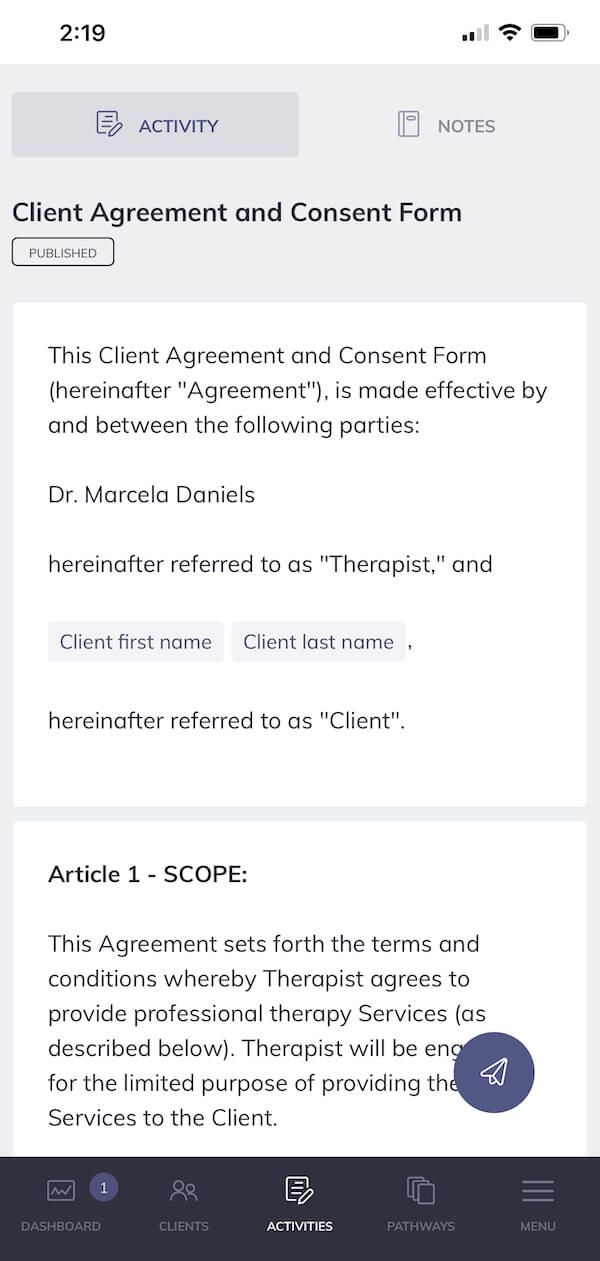

1. Use contracts and informed consent

This initial step in the therapy process can serve as a useful opportunity to outline rules and guidelines for appropriate behavior and communication.

One approach to establishing these expectations is to design and share a standardized set of client intake materials, which can be done digitally using a blended care tool such as Quenza (pictured here).

One of the benefits of providing digital informed consent and agreement documents is that it can facilitate better documentation and record keeping for practitioners.

It also allows clients to absorb important information at their own pace, which is preferable to feeling rushed at the beginning of their first therapy session.

However, therapists should always take care to provide consent forms and contracts such as these in conjunction with a face-to-face discussion and opportunities to ask questions about expectations and boundaries.

2. Keep track of time

Be mindful about deviating from session time limits defined in therapy–client contracts or during the informed consent process. Likewise, explicitly establish expectations about punctuality and the consequences if a client repeatedly arrives late to sessions.

If you find yourself responding to client emails or phone calls during time dedicated to other tasks or violating other agreements put in place, pause and reevaluate.

Consider politely reminding your client of the boundaries you set around your time at the beginning of the therapy relationship and letting them know when it is reasonably acceptable to contact you and expect a response.

Should you regularly exceed your time limit with certain clients during face-to-face sessions, place a clock in a visible but non-intrusive location. Remember that it is acceptable and even helpful to glance at the clock occasionally to keep you and your client on track.

3. Be mindful of self-disclosure

The American Counseling Association notes that when used sparingly, professionally, and appropriately, counselor self-disclosure can cultivate trust and empathy and strengthen the therapeutic alliance. However, when used too liberally or inappropriately, it can remove the focus from the client and derail progress (Bray, 2019).

Before self-disclosing, therapists should take care to explore any possible underlying motives for doing so, such as personal validation, and consider whether the information risks undermining the client’s perception of the therapist’s competence or professionalism (Sadighim, 2014).

4. Remain conscious of personal feelings

If you find yourself excited about spending time with a particular client, explore this feeling in a supervision or consultation session. Discussing social or romantic feelings about a client with your colleague or supervisor may feel anxiety provoking, but this is a perfect use of consultation.

Explore with your colleague or supervisor the emotions you’re experiencing and devise a plan to manage or problem solve them. In the end, this may involve referring the client to another therapist or coach.

5. Consider the implications of physical touch

Therapists’ attitudes toward physical touch may stem somewhat from their training and therapeutic approach. For instance, analytically trained therapists may be less likely to hug their clients, while humanistically trained therapists might be more likely to do so.

While physical, nonsexual touch does not intrinsically violate ethical standards, it is important to consider your boundaries, the client’s boundaries, and the implications of touch. Likewise, it is important to ensure that the client feels in control.

When in doubt, take your cues from the client. For instance, if your client is upset and you’re considering offering consolation as a hug, ask for their consent first.

6. Practice judicious gift giving

Different therapists will have different philosophies on exchanging gifts with clients. Some have been taught that receiving or giving gifts is never acceptable, while others think these practices are acceptable under certain circumstances. Again, this will often depend on a therapist’s training.

Presently, none of the ethics codes for major therapy organizations prohibit gifts (Zur, n.d.b). Still, it is recommended that any exchange of gifts and related conversation is clearly documented in your client notes.

Interestingly, in some cultures, small gifts are a token of respect and gratitude. Therefore, besides considering a gift’s monetary value, therapists should consider the motivations and symbolism underlying the exchange of gifts, taking culture, ethnicity, therapeutic style, client history, and diagnosis into account.

Communicating Boundaries With Demanding Clients

Getting explicit about boundaries, roles, and responsibilities at the beginning of a therapeutic relationship can help prevent problems later down the line. However, even following this initial discussion, therapists may find that some clients continually push boundaries.

Besides reviewing established boundaries periodically throughout the therapeutic relationship, here are a few other steps you might take:

- Provide praise and positive reinforcement when the client adheres to boundaries.

- Try to speak assertively as soon as possible when boundaries are crossed, describing why a particular behavior was inappropriate.

- Consider establishing a boundary management plan by stating what will happen if the boundary is crossed again.

- If you work as part of a team or clinic, consider including a colleague in a difficult boundary-defining conversation.

- If you are uncertain whether a boundary has been crossed, consult your association’s ethics code and trusted colleagues and maintain documentation of the incident.

- Consider referring the client to another coach or therapist if you do not feel comfortable or competent managing a particular client’s difficulty adhering to boundaries.

A Note on Boundaries With Social Media and Phone Calls

A good general rule is to include a formal social networking policy and boundaries around social media as part of the informed consent process (Lannin & Scott, 2013).

For instance, you might specify that you will not connect with clients on social media platforms or, specifically, accept their friend requests on Facebook.

To reinforce this, therapists may find it helpful to keep separate personal and professional profiles and secure their privacy settings on personal profiles (Bratt, 2010; Myers, Endres, Ruddy, & Zelikovsky, 2012).

In addition, draw boundaries around the purpose of text messaging and phone calls in your informed consent process. For example, you might confine texts and phone calls to discussions about administrative issues, such as scheduling appointments.

In determining these boundaries around calls and messaging, consider your therapeutic approach and whether constant availability or responsiveness may foster unhealthy dependency or limit opportunities for clients to learn to problem solve independently.

3 Firm ways to set therapy boundaries – Mark Tyrrell

4 Helpful Worksheets and Books on the Topic

Hopefully, you now understand some useful strategies for establishing healthy boundaries with your therapy clients. For more ideas, look at some of these valuable worksheets and books on the topic.

1. Practitioner’s Guide to Ethical Decision Making – Dr. Holly Forester-Miller and Dr. Thomas E. Davis

This guide, designed to assist members of the American Counseling Association, serves as a step-by-step exercise that counseling professionals can use to arrive at decisions and address ethical dilemmas in their work.

Find the book at Counseling.org.

2. Assertiveness Review

It is helpful for therapists to reflect upon the situations in which they need to set boundaries and consider how they would like to react in the future. This useful worksheet facilitates thinking about when and how being more assertive would be valuable.

3. Preventing Boundary Violations in Clinical Practice – Prof. Thomas Gutheil and Archie Brodsky

This book uses practical case vignettes to explore how therapists can responsibly handle a range of possible boundary violations, including physical touch, gift giving, and more.

Find the book on Amazon.

4. Ethics in Psychology and the Mental Health Professions: Standards and Cases (4th edition) – Dr. Gerald P. Koocher and Prof. Patricia Keith-Spiegel

This book contains over 700 illustrative case studies exploring ethical challenges faced by mental health professionals and addresses topics ranging from social media to cultural considerations.

Find the book on Amazon.

A Look at Boundaries With Challenging Clients

This is because therapy is a profession that inherently involves at least some degree of psychological vulnerability between both the therapist and the client.

Further, several psychological conditions for which clients are often referred to therapists include boundary issues as a characteristic of the condition. Examples of such conditions include borderline and dependent personality disorders (Gutheil, 2005).

When working with clients who repeatedly challenge boundaries, consider some of the following pieces of advice (Gutheil, 2005):

- The therapist should remain cognizant of issues relating to transference and countertransference.

- Therapists should remain wary of how clients with particular disorders may challenge or skew the therapist’s perception or recollection of events or conversations.

- Therapists should exercise self-scrutiny when catching themselves doing things they would not usually do with clients, as these deviations from the norm may signal a developing boundary problem.

- Therapists should pay attention to whether boundary violations occur during particular phases of a session (e.g., upon rising from one’s chair to leave) and consider this as a subject for exploration in a later session.

- Therapists should discuss boundary challenges with peers during consultations and seek support.

Finally, the APA notes that therapists who feel disempowered or threatened during their interactions with clients because of repeated boundary violations may not meet standards of competence explored earlier (Behnke, 2004). The therapist may no longer feel able to offer competent services because of their emotional responses to boundary violation.

In such instances, referring the client to another source of support may be the most appropriate and ethical course of action.

PositivePsychology.com’s Resources

For more resources exploring boundaries, here are some more useful and relevant worksheets and articles:

- Different Ways To Say ‘No’ Politely

This resource facilitates assertive communication, helping the reader formulate polite sentences when setting personal limits. - Using ‘I’ Statements in Conversation

This worksheet gives the reader the confidence to set personal limits and have difficult conversations. - How to Set Healthy Boundaries: 10 Examples + PDF Worksheets

This article explores what healthy boundaries look like and their necessity for effective self-care. It also offers useful examples and worksheets to facilitate an exploration of boundaries with both adults and children.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others communicate better, this collection contains 17 validated positive communication tools for practitioners. Use them to help others improve their communication skills and form deeper and more positive relationships.

A Take-Home Message

We hope we’ve given you some ideas for establishing and communicating better boundaries with your therapy clients. Throughout this process, consider your north stars to be the client’s best interests, your therapeutic approach, and established ethical guidelines.

And when in doubt, remember the three critical steps (Gutheil, 2005):

- Be professional.

- Discuss the situation with the client (and colleagues).

- Maintain clear documentation of any boundary violations.

Following these steps will ensure that you are keeping your client’s best interests at heart while also meeting your own legal and ethical obligations.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Communication Exercises (PDF) for free.

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- Barnett, J. E. (2017). An introduction to boundaries and multiple relationships for psychotherapists: Issues, challenges, and recommendations. In O. Zur (Ed.), Multiple relationships in psychotherapy and counseling: Unavoidable, common, and mandatory dual relations in therapy (pp. 17–29). Routledge.

- Barnett, J. E., & Hynes, K. C. (2015). Boundaries and multiple relationships in psychotherapy: Recommendations for ethical practice. Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. Retrieved from http://www.societyforpsychotherapy.org/boundaries-and-multiple-relationships-in-psychotherapy-recommendations-for-ethical-practice

- Behnke, S. (2004). APA’s new ethics code from a practitioner’s perspective. Monitor on Psychology, 35(4), 54.

- Bratt, W. E. V. (2010). Ethical considerations of social networking for counsellors. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 44(4), 335–345.

- Bray, B. (2019). Counselor self-disclosure: Encouragement or impediment to client growth? Counseling Today. Retrieved from https://ct.counseling.org/2019/01/counselor-self-disclosure-encouragement-or-impediment-to-client-growth/

- Forester-Miller, H., & Davis, T. E. (1995). A practitioner’s guide to ethical decision making. American Counseling Association.

- Gutheil, T. G. (2005). Boundary issues and personality disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 11(2), 88–96.

- Gutheil, T. G., & Brodsky, A. (2011). Preventing boundary violations in clinical practice. Guilford Press.

- Gutheil, T. G., & Gabbard, G. O. (1993). The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: Theoretical and risk-management dimensions. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(2), 188–196.

- Koocher, G. P., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2016). Ethics in psychology and the mental health professions: Standards and cases (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Lannin, D. G., & Scott, N. A. (2013). Social networking ethics: Developing best practices for the new small world. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(3), 135–141.

- Myers, S. B., Endres, M. A., Ruddy, M. E., & Zelikovsky, N. (2012). Psychology graduate training in the era of online social networking. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(1), 28–36.

- Sadighim, S. (2014). The big reveal: Ethical implications of therapist self-disclosure. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 49(4), 22–27.

- Zur, O. (n.d.a). Dual relationships, multiple relationships, boundaries, boundary crossings & boundary violations in psychotherapy, counseling & mental health. Zur Institute. Retrieved from https://www.zurinstitute.com/boundaries-dual-relationships/#

- Zur, O. (n.d.b). Professional organizations’ codes of ethics on gifts in psychotherapy & counseling. Zur Institute. Retrieved from https://www.zurinstitute.com/ethics_of_gifts_in_therapy.html

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Thanks,