The Vital Importance and Benefits of Motivation

Being passive is not our default mode as human beings.

Being passive is not our default mode as human beings.

Otherwise, we would have been born as a sloth or a panda bear (no offense to these lovely creatures).

It is in our nature to strive, to want, and to move in a direction of something we desire and deem valuable.

Action may not always bring happiness, but there is no happiness without action.

William James

This article explains the reasons why understanding human motivation is important and well worth the time spent on learning to increase it. It lists many benefits of healthy motivation and distinguishes the types of motivation that are more effective in dealing with our complex and rapidly changing environment.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Why is Motivation Important?

Why is it important to understand motivation? Why do we care about what people want and why they want it? How about because it can improve our lives.

Understanding motivation gives us many valuable insights into human nature. It explains why we set goals, strive for achievement and power, why we have desires for psychological intimacy and biological sex, why we experience emotions like fear, anger, and compassion.

Learning about motivation is valuable because it helps us understand where motivation comes from, why it changes, what increases and decreases it, what aspects of it can and cannot be changed, and helps us answer the question of why some types of motivation are more beneficial than others.

Motivation reflects something unique about each one of us and allows us to gain valued outcomes like improved performance, enhanced wellbeing, personal growth, or a sense of purpose. Motivation is a pathway to change our way of thinking, feeling, and behaving.

Benefits of Motivation

Finding ways to increase motivation is crucial because it allows us to change behavior, develop competencies, be creative, set goals, grow interests, make plans, develop talents, and boost engagement. Applying motivational science to everyday life helps us to motivate employees, coach athletes, raise children, counsel clients, and engage students.

The benefits of motivation are visible in how we live our lives. As we are constantly responding to changes in our environment, we need motivation to take corrective action in the face of fluctuating circumstances. Motivation is a vital resource that allows us to adapt, function productively, and maintain wellbeing in the face of a constantly changing stream of opportunities and threats.

I have learned from my mistakes, and I am sure I can repeat them exactly.

Peter Cook

There are many health benefits of increased motivation. Motivation as a psychological state is linked to our physiology. When our motivation is depleted, our functioning and wellbeing suffer.

Some studies show that when we feel helpless in exerting control for example, we tend to give up quickly when challenged (Peterson, Maier, & Seligman, 1993). Others have proven than when we find ourselves coerced, we lose access to our inner motivational resources (Deci, 1995).

High-quality motivation allows us to thrive, while its deficit causes us to flounder. Societal benefits of increased motivation are visible in greater student engagement, better job satisfaction in employees, flourishing relationships, and institutions.

But unhealthy fluctuations in motivation also explain addiction, gambling, risk-taking, and excessive internet usage. The motivation that underlies addictive behaviors shares the neurological underpinning associated with dopamine centric rewards system and tricky inner working of the pleasure cycle.

This makes it challenging and often difficult to change behavior in situations involving addiction. See our article on Motivational Interviewing to learn more about the stages of change and motivational interviewing techniques practitioners use to motivate clients to change unwanted behaviors.

The distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation goes back to Deci and Ryan’s (2008) Self-Determination Theory of motivation.

Extrinsic motivation involves engaging in an activity because it leads to a tangible reward or avoids punishment.

Intrinsic motivation involves doing something because it is both interesting and deeply satisfying. We perform such activities for the positive feelings they create. Studies have consistently shown that intrinsic motivation leads to increased persistence, greater psychological wellbeing, and enhanced performance.

Deci and Ryan (2008) assume that humans are naturally self-motivated, curious, and interested, but the right conditions must be in place to be intrinsically motivated.

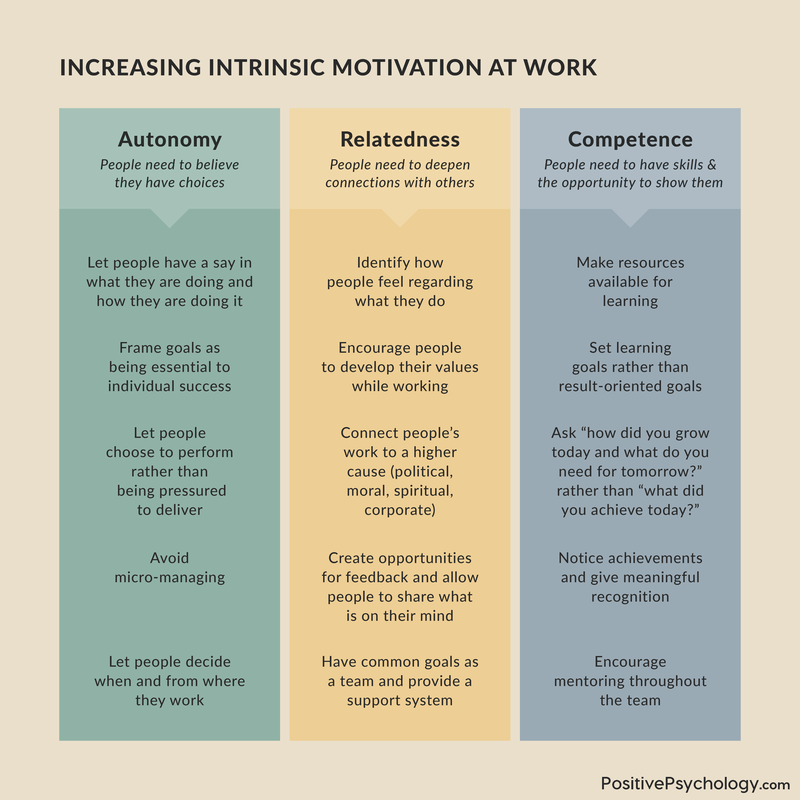

The three basic and universal psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence are foundational for human flourishing and optimal motivation, according to Susan Fowler (2019).

Satisfying the need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence leads to engaged, passionate individuals doing high-quality work in any domain. Therefore, we share tips and ideas for building the ideal working environment to promote intrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic Motivation

Is any source of motivation more potent or more effective in motivating people than the other? Are people primarily motivated by internal motives or by external rewards, or are people driven equally by internal and external triggers?

Human motives are complex, and as social creatures, we are embedded into our environment, and social groups are often an important source of influence through the presence of rewards and considerations of potential consequences of our choices on those around us.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) explains how external events like rewards or praise sometimes produce positive effects on motivation, but at other times can be quite detrimental (Ryan & Deci, 2008). The hidden cost of certain types of rewards is that they undermine intrinsic motivation by decreasing the sense of autonomy and competence.

There is a tradeoff between satisfying and undermining the need for competence when we offer rewards (Reeve, 2018). This form of extrinsic motivation also can undermine our sense of autonomy since rewards are used for both purposes: to control behavior and to affirm someone of their level of competence. We want to reward in a way that encourages competence without threatening the sense of autonomy.

My grandfather once told me that there were two kinds of people: those who do the work and those who take the credit. He told me to try to be in the first group; there was much less competition.

Indira Gandhi

Rewards should be reserved for activities that are not interesting and should be given when not expected. Praise is preferable to monetary rewards, for example, as it supports psychological needs and is of more lasting value (Reeve, 2018).

Similarly to rewards, imposed goals were found to narrow focus and impair creativity. Studies show that imposed goal setting increases unethical behavior and risk-taking, narrows focus, and decreases cooperation, intrinsic motivation, and creativity. This is an excellent example of goals gone wild (Pink, 2009).

Much of contemporary research shows that intrinsic motivation is more effective more often and of more enduring value. In some circumstances, however, extrinsic motivation may be more appropriate, as in the case of uninteresting activities.

It is also possible to make use of incentives more effective by encouraging people to identify with it and integrate it into their sense of self (Reeve, 2018). To give an example of identifying and integrating extrinsic motives respectively would be like describing the difference between saying: “I do this because it’s the right thing to do” versus “I do this because I am a good person.”

Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation is inherent in the activities we perform for pure enjoyment or satisfaction. We engage in intrinsically motivated behavior because we want to experience the activity for its own sake. Unlike extrinsically motivated behavior, it is freely chosen (Deci, & Ryan, 1985).

Intrinsic motivation can be driven by curiosity, which is linked to a desire to know and motivates us to learn and explore our environment for answers (Loewenstein, 1994). Intrinsic motivation can also come from the need to actively interact and control our environment. The effectance motivation theory explains how intrinsic motivation drives us to develop competence (White, 1959).

Finally, Allport’s concept of the functional autonomy of motives explains how behavior originally performed for extrinsic reasons can become something to perform for its own sake (1937).

Destiny is not a matter of chance; it is a matter of choice. It is not a thing to be waited for, it is a thing to be achieved.

William Jennings Bryan

When it comes to intrinsic motivation, it is important to distinguish between activities that are intrinsically motivating and the development of what Csikszentmihalyi calls autotelic self (1975, 1988). The term autotelic is derived from the Greek word auto, which means self and telos meaning goal.

Intrinsic activities are self-contained because performing them is a reward in itself. The autotelic experience produced by an intrinsic activity makes us pay attention to what we are engaged in for its own sake and away from consequences. When the experience is intrinsically rewarding, life is justified in the present and not tied to some hypothetical future gain.

The most important characteristic of the autotelic experience is its intrinsically motivated nature. Professor Csíkszentmihályi, who coined the terms flow, defined this optimal experience as a pursuit of enjoyable, interesting activities for the sake of the experience itself, where the satisfaction derived from the action itself is the motivational factor (1990).

An autotelic self actively seeks out intrinsically motivating activities. A person who is said to have an autotelic personality values opportunities where she or he can experience complete absorption in the tasks at hand. They transform the self by making it more complex. A complex self has these five characteristics:

- Clarity of goals

- Self as the center of control

- Choice and knowing that life is not happening to you

- Commitment and care for what you are doing

- Challenge and increased craving for novelty (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, 1988).

Autotelic self, according to Csikszentmihalyi, tends to create order out of chaos because it sees a tragedy as an opportunity to rise to the occasion and tends to focus all the psychic energy on overcoming the challenge created by the defeat (1990). Cultivating autotelic personality is, therefore, a worthwhile endeavor as it breeds resilience.

Falko and Engeser, in their recent study on motivation and flow, used the term activity related motivation as a substitute for intrinsic motivation to speak more specifically to the “Extended Cognitive Model of Motivation” (2018).

They measured various activity-related incentives in qualitative and quantitative ways and found the experience of flow to represent one of the most intensely studied. Positive incentives stemming from learning goal orientation, experience of competence, interest, and involvement lead to us engaging in activities purely for the enjoyment of it (Falko & Engeser, 2018).

Our plans miscarry because they have no aim. When a man does not know what harbor he is making for, no wind is the right wind.

Seneca, 4 B.C.–A.D. 65

Professor Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi, who developed the theory of flow, argues that happiness depends on inner harmony, not on the control we can exert over our environment or circumstances, and therefore describes flow as an optimal state of being that brings order to consciousness.

He discovered, in his years of research into creativity and productivity and interviews with people who were deemed successful in a wide range of professions and many of whom were Nobel Prize winners, that the secret to their optimal performance was their ability to enter the flow state frequently and deliberately.

They would describe feeling a sense of competence and control, a loss of self-consciousness, and such intense absorption in the task at hand that they would lose track of time.

Many of the most accomplished and creative people are at their peak when they experience “a unified flowing from one moment to the next, in which we feel in control of our actions, and in which there is little distinction between self and environment; between stimulus and response; or between past, present, and future” (Csíkszentmihályi, 1997, p. 37).

The contemporary research on motivation shows that intrinsic motivation that originates from internal motives is often experienced as more immediate and potent than extrinsic motivation.

Today we know that intrinsic motivation affects the quality of behavior more, such as school work, while extrinsic motivation influences the quantity of behavior more (Deckers, 2014).

It has also been shown that intrinsically motivated goal pursuit has greater long-term outcomes because it satisfies our psychological needs for autonomy and competence, and in turn, creates more positive states which reinforce the positive feedback loop and increase the likelihood of repetition (Reeve, 2018).

Self-motivation

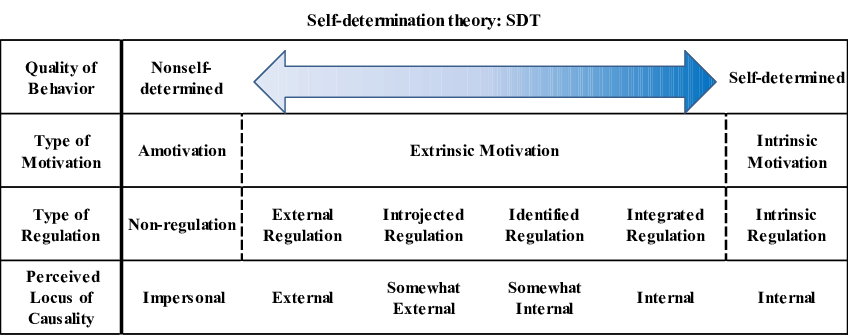

No one knows more about self-motivation that the authors of self-determination theory. Based on the assumption that we have an innate tendency for personal growth toward psychological integration, the self-determination theory of Ryan and Deci proposed that all behavior can be understood as lying along a continuum of external regulation, or heteronomy and true self-regulation, or autonomy (2008).

Ryan and Deci distinguish varying degrees of external motivation based on the level of autonomy present while engaging in the desired behavior. On one end, there is the external regulation of behavior where rewards are used purely to control behavior, and compliance occurs to avoid consequences and is defined as one where there is no autonomy present.

They explain that while external regulation, as in the form of rewards, can control behavior, it does not constitute motivation per se.

In all human affairs there is always an end in view—of pleasure, or honor, or advantage.

Polybius, 125 B.C

We can also be motivated by the avoidance of guilt and by the need to build self-esteem. This form of self-regulation of behavior is characterized by low autonomy and a language of “I should” and “I have to.”

When we are motivated by the contingencies related to our self-esteem and impose pressures on ourselves for fear of shame or failure, we are said to have introjected regulation. This form of regulation, while more effective than external motivation, remains ambivalent and unstable because it is accompanied by inner conflict, tension, and negative emotions (Ryan & Deci, 2008).

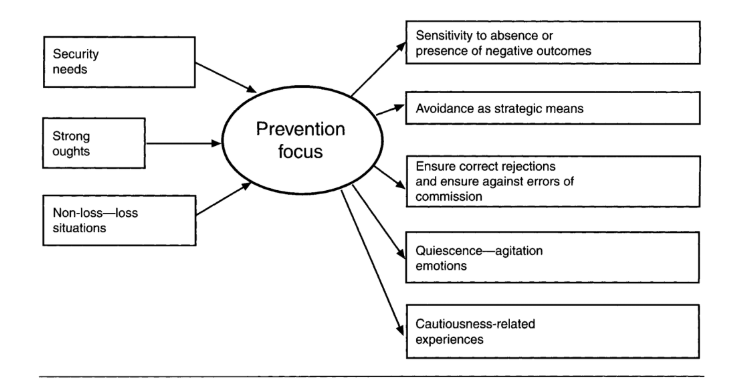

These are closely related to what is known in wellbeing research as prevention focus orientation, where emotional regulation is driven by security needs and avoidance (Kahneman, Diner, & Schwartz, 1999).

When we consciously accept behavior as important, and when we truly value the outcome, this provides strong incentives and leads to identification. This more self-determined form of regulation is particularly important when it comes to the maintenance of behaviors that involve activities that are not inherently interesting or enjoyable.

When we identify with the regulation AND coordinate with other core values and believes, we are said to have the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation – integrated regulation. This form of regulation occurs when those values become a part of the self and become congruent with one’s sense of identity.

That leads to the most positive and enduring outcomes of external motivation because a person has archived full autonomy (Reeve, 2018).

This form of regulation is very much like intrinsic motivation because we engage in the behavior willingly. It is entirely self-determined, but unlike intrinsic motivation, it does not have to involve activities that are enjoyable or interesting. This is particularly important to behavioral change in clinical settings where the level of internalization and integration for non-intrinsically motivated behavior is required.

It is never too late to be what you might have been.

George Eliot

When it comes to self-motivation in behavioral change, the autonomy versus control orientation can also play a role in maintaining behavioral change over time. Autonomy-oriented individuals generally succeed in maintaining their long-term changes in behavior (e.g., weight loss, smoking cessation), whereas control-oriented individuals generally fail to maintain such behavior change over time.

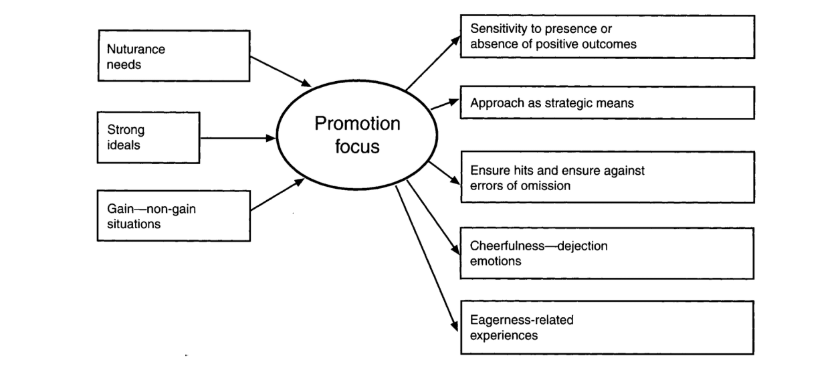

Autonomy causality orientation is closely linked to prevention focus orientation, where emotional regulation is driven by the possibility of positive outcomes and approach motivation (Kahneman, Diner, & Schwartz, 1999).

Autonomy-oriented individuals see everything in their environment and their responses to it as a matter of their own choice, and this perspective can be empowering and a great source of intrinsic motivation.

They tend to scan their environment for opportunities, they take initiative, set their own goals, and they take an equal interest in their environment as well as their own inner experience. They have an internal locus of control and behave with a strong sense of volition. They understand that their focus determines their reality, and they have a sense of shaping their destiny (Reeve, 2018).

Autonomy causality orientation characterizes individuals with a specific mindset where they rely on internal guides to regulate behavior in contrast to those who are control-oriented and attend to external guides like social queues and environmental incentives — this locus of control effects motivation and perseverance.

When we feel our behavior is something we initiate and regulate, we can make and sustain changes. This is in contrast to those, who at the other end of the spectrum, take on the victim of circumstances mentality (Reeve, 2018).

See our blog post 19 Best Books on Self-Discipline and Self-Control.

A Motivational Quote

Everybody Knows:

You can’t be all things to all people.

You can’t do all things at once.

You can’t do all things equally well.

You can’t do all things better than everyone else.

Your humanity is showing just like everyone else’s.

So:

You have to find out who you are, and be that.

You have to decide what comes first, and do that.

You have to discover your strengths, and use them.

You have to learn not to compete with others,

Because no one else is in the contest of *being you*.

Then:

You will have learned to accept your own uniqueness.

You will have learned to set priorities and make decisions.

You will have learned to live with your limitations.

You will have learned to give yourself the respect that is due.

And you’ll be a most vital mortal.

Dare To Believe:

That you are a wonderful, unique person.

That you are a once-in-all-history event.

That it’s more than a right, it’s your duty, to be who you are.

That life is not a problem to solve, but a gift to cherish.

And you’ll be able to stay one up on what used to get you down.

11 Top Motivational Videos

There are dozens of motivational videos and channels on YouTube, but unfortunately we could not list them all. Instead, we picked a few we see as top motivational videos.

1. Dream

In order to achieve great things, you must first believe in yourself and then have a dream big enough to motivate you.

2. The Last Lecture

Even if faced with terminal cancer, it’s possible to find and celebrate the joy in your life.

3. Remember Me

When all is said and done, being human, exactly who you are, is more amazing than all the technology in the world.

4. Look Up

Don’t let yourself be hypnotized by technology. Be in the moment and experience the wonder of direct connections.

5. Why We Do What We Do

If you understand why you’re motivated and inspired, it’s easier to become motivated and inspired. Tony Robbins explains it all.

6. Amazing Grace

The classic spiritual hymn rendered a cappella by the amazing and always creative Jesse Campbell.

7. Never Quit

Regardless of the obstacles that life throws your way, if you continue to pursue your dreams you will get results.

8. The Surprising Science of Happiness

Dan Gilbert challenges the idea that we’ll be miserable if we don’t get what we want and explains how to feel truly happy even when things don’t go as planned.

9. Unbroken

Dedication to your goals keeps you moving forward, even if you encounter obstacles.

10. How Bad Do You Want It?

Sometimes it’s just a matter of wanting success so badly that you’ll do whatever it takes to win.

11. Excuses

Even if you’ve got an uphill battle to fight, you keep fighting. Because if you just give up, you’ve lost.

A Take-Home Message

Context matters, and it is not a question of which type of motivation is more important, but instead, awareness of where we lack the necessary balance to create the ideal catalyst for goal achievement.

The significant problems of today cannot be solved at the same level of thinking that created them.

Albert Einstein

External events can become prompts for the desired behavior and can help to reinforce it, but to notice those we need to be in positive mental and emotional states, away from the sense of learned helplessness, as defined by Dr. Martin Seligman.

Often our goals must also represent something of value to us and satisfy our psychological needs as defined by Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory, especially to create the energy necessary to persist (Reeve, 2018).

Do you have a story of your ideal catalyst for goal pursuit? Share it with us here.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- Beck, R. C. (2004). Motivation: Theories and principles (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1997). Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: State of the science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 182.

- Deckers, L. (2014). Motivation: Biological, psychological, and environmental (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- DeCatanzaro, D. A. (1999). Motivation and emotion: Evolutionary, physiological, developmental, and social perspectives. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Edwards, D. C. (1999). Motivation and emotion: Evolutionary, physiological, cognitive, and social influences. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Ferguson, E. D. (2000). Motivation: A biosocial and cognitive integration of motivation and emotion. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Fowler, S. (2019). Master your motivation: Three scientific truths for achieving your goals. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Franken, R. E. (2006). Human motivation (6th ed.). Wadsworth Thomson Learning, Belmont, CA.

- Gallwey, W. T., Hanzelik, E., & Horton, J. (2009). The Inner Game of Stress: Outsmart Life’s Challenges and Fulfill Your Potential [Kindle iOS version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com

- Gollwitzer, P. M. & Bargh, J. A. (1996). The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior. Guilford Press, New York/

- Gorman (*). Motivation and emotion

- Heckhausen, J. & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Motivation and self-regulation across the life span. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwartz, N. (1999). Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Nunez, R. & Freeman, W. J. (1999). Reclaiming cognition: The primacy of action, intention, and emotion. Imprint Academic, Thorverton, UK.

- Peterson, C., Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1993). Learned Helplessness: A Theory for the Age of Personal Control. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Petri, H. L., & Govern, J. M. (2013). Motivation: Theory, research, and applications (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Reeve, J. (2015). Understanding motivation and emotion (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Sansone, C. & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Sheldon, K. M. (Ed.) (2010). Current directions in motivation and emotion. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Wagner, H. (1999). The psychobiology of human motivation. Routledge, New York.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

The article is well-thought! I appreciate the content which has nourished me a lot. Good bless that intelligence!

I am in absolute awe – fantastic culmination of fields of study to deliver a hard punching, thought provoking article👌Inspiring!

Good article. Keep it up!

Greetings! Great explanation i learned about the meaning of motivation wonderful words. Regards mentor.

Excellent description or explanation or importance of motivation thanks beata spider love you from Kashmir…

This is great!!! Thanks!!!

Everyone needs motivation, the way you explained the benefits of motivation is great. Nicely written and well explained. Good work.

This collection of videos is immensely valuable! I was glad to be reminded of the power of the autotelic self. As I deliver my lectures from home this week, the topic of resilience in the face of adversity has been a continuous theme in our discussions. How timely to receive this wonderful resource, thank you Beata. 🙂

Good stuff. Keep me posted.