What Is Appreciative Inquiry? (Definition, Examples & Model)

In an unpredictable global business environment, it’s tempting to approach strategy with specific goals already in mind.

In an unpredictable global business environment, it’s tempting to approach strategy with specific goals already in mind.

More often than not, these are problem-focused and aimed at mitigating threats.

Businesses commonly focus on what’s not working and adopt ‘root cause’ mindsets, only to find themselves facing a set of different, but related questions down the line.

Questions like “How can we fix our lack of engagement?” “What do we do about low motivation?” “Or, why are people just not on board?”

The Appreciative Inquiry Model is one of the key positive organizational approaches to development and collective learning. Here, we look at how it has blossomed into one of the most influential movements for positive organizational development in recent decades.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Strengths Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help your clients realize their unique potential and create a life that feels energizing and authentic.

This Article Contains:

- What is Appreciative Inquiry?

- A Brief History

- A Look at David Cooperrider

- The Model and Theory

- Examples of the Approach

- Criticisms of the Method: Pros and Cons of the Framework

- What is SOAR?

- The Appreciative Inquiry Summit

- 75 PowerPoints on Appreciative Inquiry (PPT)

- 6 TED Talk and YouTube Videos

- 9 Quotes

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Appreciative Inquiry?

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a collaborative, strengths-based approach to change in organizations and other human systems. The term ‘Appreciative Inquiry’ is thus used to refer to both:

- The AI paradigm – in itself, this relates to the principles and theory behind a strengths-based change approach; and

- AI methodology and initiatives – which are the specific techniques and operational steps that are used to bring about positive change in a system (Davidcooperrider.com, 2019).

Or take our own definition:

Key Concepts in AI

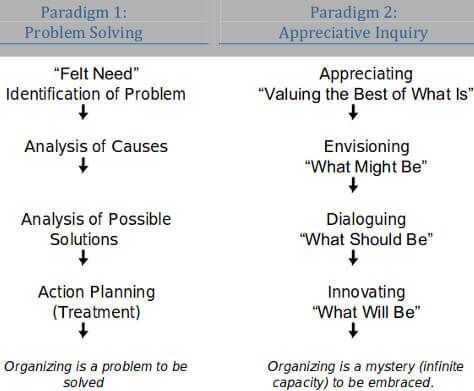

The fundamental idea behind AI is that over time, it has become increasingly common for organizations to approach change and growth from a problem-solving perspective. As firms aim to improve efficiency, survive, perform better, and boost competitiveness, AI proponents argue that there has come to be an unhealthy over-emphasis on “fixing what’s wrong”—a deficit-based approach.

AI arose as a challenge to these ingrained assumptions and proposed that organizations can benefit instead from what is called a strengths-based or affirmative approach (Hammond, 2013). This affirmative approach, in turn, assumes that each human system has a positive core of strengths.

This positive core is not vastly different from the way we view organizational strengths in conventional management literature. In essence (and loosely paraphrased from the authors), they can be seen to encompass (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005):

- The values, beliefs, and capabilities of our organization when it’s ‘at its best’; and

- Collective understandings around what makes up the best of us.

As a concept in positive organizational psychology, AI is probably best understood by looking at its evolution over time.

A Brief History

It helps to know a bit about scientific management and ‘Taylorism’ to see how and why AI came to be.

Scientific Management

Most organizational leaders and managers will already know about scientific management, but for those who aren’t familiar, this was a school of thought that rose to prominence in the late 19th Century. The goal of Scientific Management was boosting the efficiency of workflows by looking at them analytically and eliminating waste.

At that time, Frederick Taylor, an American engineer, was inspired to apply rigorous scientific techniques to break down and improve how people worked. Broadly, this was through timing, simplifying and standardizing tasks.

The resulting approaches have been criticized heavily for promoting the view of firms as machines, rather than entities of people. Another nice parallel is that it placed emphasis quite squarely on the resources, rather than the human part of human resources. A direct quote from the man himself gives an example:

“In our scheme, we do not ask the initiative of our men. We do not want any initiative. All we want of them is to obey the orders we give them, do what we say, and do it quick.”

(Taylor, 1919)

Fixing Broken Machines

Scientific Management in its original form has not been popular for close to a century. However, AI proponents point to lots of evidence that ‘deficit-centered’ thinking has remained heavily embedded in managerial and organizational practice (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987).

Changing organizations, in this sense, was about identifying, establishing, and fixing things that weren’t working—summarized neatly as ‘inquiry into deficit experiences’ by Bushe (2013), an AI expert.

Commonly cited examples include organizational needs analyses, problem definition, root cause analyses, and similar.

Toward a Strengths-Based Approach

In reaction to this perceived overemphasis, AI has emerged as an alternative approach to organizational change and development; an affirmative approach that focuses inquiry on what’s right, what’s working, and how to work toward a desired vision (Davidcooperrider.com, 2019).

The Appreciative Inquiry Model is, as noted, based on the principle that positive organizational futures can be reached through collective involvement and methods that “affirm, compel, and accelerate anticipatory learning” (Cooperrider et al., 2008).

A far cry from dissecting past mistakes and defining a corrective path forward. A little further on, I’ll look closer at the model and theory in more detail.

Relevant: 18 Appreciative Inquiry Workshops, Training, and Courses

A Look at David Cooperrider

David Cooperrider is often considered the pioneer of the Appreciative Inquiry Model. However, the paradigm itself was developed during the ‘80s by both Cooperrider and Suresh Srivastva, his then mentor.

The Power of Questions

Cooperrider describes his “Ah-Ha!” moment as having occurred when he and a colleague were doing action research (see our post on appreciative inquiry research) for an organizational development project (Bushe, 2013). Specifically, the team found themselves in an increasingly hostile and negative atmosphere and decided to change their approach.

Rather than inquiring into what wasn’t working, Cooperrider and his colleague decided to ask about what was working—albeit for a different company (Barrett & Cooperrider, 1990). The brainwave here was that inquiry itself can powerfully shape the way we view and develop human systems. That led to Cooperrider’s Ph.D. on AI in 1986.

From Research to Interviews to Organizational Development

What Cooperrider actually had at this point was a potentially transformative insight into how qualitative social science research could be improved.

The paradigm shift for organizational change, that is, didn’t happen instantly. Bushe (2013), who covers the history of AI in much more detail, describes how the inquiry approach was first taught to employees so that they could interview other staff in turn with the new methods. It was received positively as the benefit for ideas generation quickly became apparent.

David Cooperrider then began working with others to explore how this ‘social constructionism’ might be applied to organizational change, amongst other things. By 1997, the ‘4D model’ he had laid the groundwork for, had become the Appreciative Inquiry Model we know today.

The Model and Theory

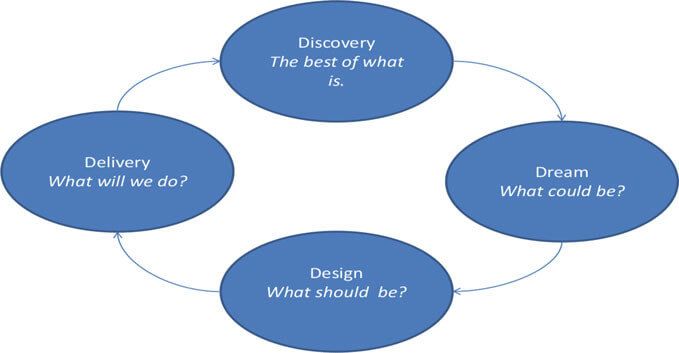

Any organizational development practitioner will know that frameworks abound in the field. The 4D model generally refers to a visual representation of the four steps of an AI initiative:

- Discovery;

- Dream;

- Design;

- and Destiny.

You will, however, commonly see a fifth step added, for Define, this relates simply to what David Cooperrider describes as selecting an affirmative topic. An affirmative topic, in turn, is the focus of your intervention—there may be one or there may be multiple foci. Examples may include greater customer satisfaction, safer work environments, or more efficient value delivery (Kessler, 2013).

Below is an example of the AI Model with Define left out.

Steps in the 4D Model

The Define step is an important part of determining how the following steps will flow. Kessler (2013) emphasizes the importance of using inspiring language to frame the focus of your intervention. So, greater customer satisfaction might become what he describes as “inspiring fanatically loyal customers”.

Affirmative topics now established, here are the phases (Ludema et al., 2006):

1. Discover

The focus during this phase is searching for and identifying what gives the organization life. Past successes can be discussed and explored, and in each instance, the goal is to hone in on what has enabled them.

This is all about active inquiry, and internal stakeholders can ask each other questions to discover what Ludema and colleagues call “the best of what is”. While this is focused on uncovering strengths, it’s also a useful way to shift current mindsets and vocabulary away from deficit-focused thinking.

2. Dream

The Dream phase is about imagining potential positive futures for the organization. Because a wide range of participants has ideally been engaged in the AI process, these will represent multiple perspectives, opinions, and understandings.

The unconditional positive questions that have been developed will ideally unlock creative, constructive visions and possibilities. Through positive language and imagery, participants co-create futures and positive outcomes.

3. Design

Co-creation continues through this phase, but the focus shifts to debating and discussing the possibilities already generated.

The goal is to reach a shared vision or value that the team or participants see as having real, positive potential. Individual aspirations thus become shared, in what is ideally an inclusive, safe, and supportive environment where everybody feels heard.

4. Destiny

The goal of this final phase (formerly called Delivery) is to construct futures “through innovation and action” (Ludema et al., 2006: 158). The vision, system, or structures that have been designed are committed to as possible means of achieving them are further refined through individual commitment.

It’s worth mentioning that the Destiny phase of the 4D model is not strictly defined in terms of how it should proceed. Individual practitioners and theorists, Kessler argues, will vary in their encouragement of structure or improvisation around this phase (Kessler, 2013).

Basic Principles of Appreciative Inquiry

As AI has come to be more widely practiced, we’ve also seen many contrasting and conflicting practices that supposedly fall under the AI umbrella. This is something Bushe (2013) attributes to an initial lack of formal methodology—Professor Cooperrider was hesitant at first to publish any. But toward the earlier part of last decade, he and Dr. Diana Whitney from the Taos Institute developed 5 principles for AI practice.

1. The Constructionist Principle

This posits that our subjective beliefs about what is true, determine our actions, thoughts, and behaviors. The language that we use daily is pivotal in how we co-construct our organizations, and this includes the language we use for inquiry.

Inquiry, in itself, is about generating and inspiring new ideas, visions, and stories that can potentially lead to action (Cooperrider & Whitney, 1999).

2. The Simultaneity Principle

This suggests that our inquiries into human systems can cause them to change. The first questions we ask can shape how people think about and discuss things; this, in turn, affects how they learn things and discover.

There is no such thing as a neutral question, in the sense that passionate and persistent inquiries in specific directions will lead to change in those directions (Cooperrider & Whitney, 1999; Whitney & Trosten-Bloom, 2003).

3. The Poetic Principle

The third principle holds that we can choose—or not—to study organizational life to make a difference. Life in human systems, such as organizations and teams, is co-authored and told in stories.

Our choice of vocabulary can trigger feelings, images, concepts, and understandings, and AI is about using inquiry to create positive, optimistic visions of the future to inspire and awaken ‘the best in people’ (Cooperrider & Whitney, 1999; Kessler, 2013).

4. The Anticipatory Principle

The Anticipatory Principle suggests that our current actions and behaviors are shaped by our visions for the future.

Through AI, we can create positive images and visions of our or an organization’s future that will impact what we do in the present (Goleman, 1987; Cooperrider & Whitney, 1999).

5. The Positive Principle

This posits that to encourage momentum, we must ask positive questions which emphasize the positive core of an organization. Lasting change relies on social connections and positive affect among people. Positive emotions such as enthusiasm, togetherness, hope, and happiness encourage creative ideas and openness to innovative ideas (Barrett & Fry, 2005; Stavros & Torres, 2005).

These 5 AI principles are the most commonly cited and have now become well-established. As Appreciative Inquiry practice becomes increasingly more popular, however, we are seeing emergent principles being proposed. Among these are principles such as wholeness, enactment, awareness, free choice, narrative, and synchronicity (Whitney & Trosten-Bloom, 2003; Stratton-Berkeessel & Myers, 2019).

Examples of the Approach

In this section, we’ll look in-depth at one example of applied AI for organizational change, and you’ll also find some further helpful links to more case studies on the topic.

Global Relief and Development Organization

Global Relief and Development Organization (GRDO), as introduced by Ludema and colleagues in their Handbook of Action Research (2006), is a US and Candian NGO that was involved with over a hundred other organizations worldwide.

The Context:

GRDO approached the authors with what it perceived to be a problem with the current organizational capacity evaluation system for its partners. In describing the situation to their consultants, they mentioned lack of (internal and external) stakeholder engagement with the system; people didn’t support it and they viewed it as a tedious imposition.

Already implicit in their description of the system, was deficit-based vocabulary and suggestions of blaming—both between stakeholder organizations and GRDO itself. Also, the authors note, GRDO was not able to view itself as an equal partner in what was inherently supposed to be a capacity building process and was not being seen as such.

Affirmative Topic:

The first step, as such, was to reframe the perceived problem positively and define an affirmative topic. To this end (or beginning), the consultants asked questions aimed at uncovering GRDO’s ‘deeper yearning’. According to Johnson and colleagues, the first key questions were:

“What do you really want from this process? When you explore your boldest hopes and highest aspirations, what is it that you ultimately want?”

The Define step thus led to several topics; GRDO wanted many positive things, which came down to (Ludema et al., 2006):

- Learning from each other about how they could build vibrant, healthy, strong NGOs; and

- Discovering new ways of collaborating with their partners as equals.

Discovery:

A global team was formed which was made up of stakeholders from GRDO’s different regions across the world, and large-group retreats were organized so that both GRDO and its stakeholders could get familiar with AI. They came up with slightly different versions of the AI Interview Protocol shown below.

|

Appreciative Interview Protocol

|

Source: Ludema et al. (2006)

With their unconditional positive questions to guide the inquiry, the different partner NGOs returned to the country they worked in to carry out ‘listening tours’ (Ludema et al., 2006). These involved participatory inquiry with community members that the NGOs were working with, to include as many voices as possible while discovering the positive core strengths of GRDO and its partners.

Thousands of participants were involved in this stage, which took place over the course of a year.

Dream:

GRDO and its NGO partners met again at large-group retreats to share the strengths and stories from their inquiries. This helped them voice their visions of what a positive organizational future might look like, and start generating ideas for a new strategic approach. Ludema and colleagues describe this stage as the start of the redesign (Ludema et al., 2006: 162):

“A virtual explosion of positive stories were being shared and the way GRDO and its partners talked about themselves, each other, and their joint work was beginning to shift from a conversation of deficit to a conversation of possibility.”

Design:

In collaboration with its partners, GRDO began to systematically explore what social structures might bring these visions to life. This took place on a global scale, with hundreds of meetings conducted. During these, participants created regionally responsive architectures—”provocative propositions”—that could link the discovered strengths with the ideal possible futures, or what ‘might be’.

Through further collaboration, these developed into potential new capacity-building systems that were fundamentally different from the previous approach GRDO and its partners had been using. Broadly, these were more participative and devolved responsibility so local NGOs would create more relevant solutions in different countries.

The authors describe the beginnings of a shift toward more partnership-focused mindsets. The desired equality was, they recall, beginning to show itself as vocabulary changed to become more like that of partners.

Destiny:

The third and final year of GRDO and the NGOs journey saw initiatives shared and energy growing around them. Joint activities were rolled out in different regions after the final round of retreats, such as the launching of new local fundraising projects and organizational redesign to a new, less hierarchical structure.

More detail on this global AI initiative can be found in Johnson and Ludema’s (1997) book, Partnering to build and measure organizational capacity: Lessons from NGOs around the world.

More Appreciative Inquiry Examples

If you’re looking for more examples of AI in practice, try these:

- 4 Appreciative Inquiry Tools, Exercises and Activities

- How to Apply the Appreciative Inquiry Process (Incl. 5 Tips)

- 119+ Appreciative Inquiry Interview Questions and Examples

- Many more write-ups and case studies from teams and organizations, courtesy of Davidcooperrider.com.

Criticisms of the Method: Pros and Cons of the Framework

So, what are the advantages and disadvantages of the Appreciative Inquiry Model as a whole? Luckily, others before us have reviewed the literature, so we can draw our own conclusions (Drew & Wallis, 2014). Let’s look at the pro’s first.

Potential Pros of AI:

- First, AI focuses on strengths, which arguably provides organizations with energy for positive change and innovation (Ludema et al., 2006; Bright, 2009);

- Utilizing strengths also allows employees to enhance their proficiency (Linley et al., 2010);

- It encourages a learning culture through collective inquiry and equips people with the skills to discover for themselves (Conklin & Hartman, 2014);

- As such it encourages creative thinking, ideation, and potentially fosters innovative approaches (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987; Cooperrider et al., 2008);

- These, in turn, facilitate organizational adaptability – a critical competitive advantage in dynamic business environments (Basadur, 2004);

- A learning culture also encourages sustainable change (Boyce, 2003);

- By design, it aims to encourage stakeholder participation (Drew & Wallis, 2014);

- Through participation, it seeks to foster commitment rather than resistance (Lines, 2004; Drew & Wallis, 2014); and

- The 4D framework, through its structure, allows people to gain insight into actions (Bright, 2009).

There is a consistent theme through the vast majority of these potential advantages; this is that Appreciative Inquiry addresses change at a cultural level, rather than presenting an analytical approach to ‘fixing’ specific problems. Indeed, AI encourages a holistic systems approach, its fundamental premise being neither ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ (Davidcooperrider.com, 2019).

In that vein, let’s look at the potential disadvantages of Appreciative Inquiry.

Potential Cons of AI:

- AI takes considerable time—it’s not a quick fix by any stretch of the imagination (Drew & Wallis, 2014);

- Large-scale organizational change through AI can be resource-intensive, especially if participants are geographically dispersed, as with the case study above;

- It relies heavily on the extent to which a positive, supportive, and open environment for sharing can be created (Cooperrider & Whitney, 1999; Ludema et al., 2003);

- Not all stakeholders can always realistically be involved (Schooley, 2012); and

- If all stakeholders can’t be involved, this raises questions around the ethical morality of strategizing with what is not, essentially, a democratic consensus (Schooley, 2012).

To sum up the weaknesses, therefore, Drew and Wallis (2014) argue that careful planning becomes important when we consider using AI in specific contexts. Schooley (2012) would emphasize that governmental and public sector applications of AI may be particularly problematic.

What is SOAR?

In short, SOAR is a strategic framework based on AI principles. The simplest parallel with a more commonly known model would be SWOT. Both link internal firm factors with potential externalities and futures to allow an analytical approach to strategy.

A SOAR Framework

SOAR stands for (Stavros et al., 2003):

- Strengths – Similar to SWOT strengths, these relate to the existing internal factors. They can be internal resources, dynamics, or even facets of organizational structure that can be strategically leveraged for competitive advantage;

- Opportunities – These are external factors existing in the firm’s macroeconomic, industry, or market environment;

- Aspirations – Aspirations are positive potential futures for the firm, including how a company can create value. These could ideally be strongly related to a firm’s strategic vision, and ideally, collective commitment can be encouraged around this vision; and

- Results – These can be seen as deliverables, and allow for implementation and evaluation of a company’s progress as it moves toward its goals.

Below is an adapted version of Stavros et al.’s (2003) example application of SOAR. Here, it’s possible to see how Internal Factors and External Factors (from SWOT) are replaced as strategic planning categories by Strategic Inquiry and Appreciative Intent in SOAR.

| Strategic Inquiry |

Strengths What are our greatest assets? |

Opportunities What are the best possible market opportunities? |

| Appreciative Intent | Aspirations What is our preferred future? |

Results What are the measurable results? |

Source: Adapted from Stavros et al. (2003: 11; 12)

SOAR vs. SWOT

As we’d expect from an AI framework, the SOAR model begins with inquiry. This is the first of four stages that participants can go through as a group (Stavros et al., 2003):

1. Inquiry: Positive questions are asked to uncover the organization’s strengths and aspirations, and it’s a good chance for open, positive discussion about shared (or not) understandings of values and visions (Stavros et al., 2003). Where do we want to be? What strengths have helped us reach where we are now? How, and why?

2. Imagination: Participants come up with potential futures. Vision, values, and mission are co-created, and iteration can be a useful means of clarifying or re-affirming the firm’s strategic direction. The focus of the imagination phase is long-term goals for a preferred future, rather than proactive risk management with threats or weaknesses in mind.

3. Innovation: Long-term strategic goals are broken down into short-term objectives and methods for achieving them. For a specific project, this might involve developing deliverables and timeframes; in a more general sense, it is about putting systems in place to facilitate implementation.

4. Inspire: Stavros and colleagues introduce Inspire as a replacement for what is traditionally seen as control systems (i.e. in the cultural web, or in Total Quality Management). In conventional strategizing, these may refer to KPIs and incentives; in SOAR, inspire encompasses systems that encourage authentic recognition and reward.

Applying SOAR

Of course, understanding a framework isn’t the same as putting it into action. To that end, Stavros and Hinrichs (2009) outline several steps for applying the SOAR framework in their Thin Book of Soar. Their 9 steps are as follows:

- Identify stakeholders – Establish who will be taking part in the exercise and decide on how you will be meeting. In line with the holistic, collaborative aim of AI, participants should be internal stakeholders that represent different areas of the company.

- Design your AI interview – Plan out questions that you intend to use; these will, of course, be aimed at developing better insight into the organization’s positive core. Understanding its strengths, successes, and aspirations is the key motivation, so your questions should reflect these aims.

- Engage stakeholders – These will always involve internal stakeholders, and may also include external stakeholders such as partners, customers, or suppliers if it’s deemed appropriate. Use your questions to uncover positive potential futures and possibilities.

- Reframe problems – Problems will invariably arise for discussion; SOAR inquiry is about a positive focus, so reshape conversations to look at desired outcomes rather than avoiding or mitigating threats.

- Summarize – This is about clarifying and affirming the organization’s strengths—its positive core.

- Establish aspirations and identify results – This is a key part of defining or redefining the organization’s future vision, which will ideally leverage the strengths you have collectively identified. How will these look? What will they be like?

- Assess opportunities – Look at the opportunities that have been generated. Which are the most desirable? Which are new, innovative, and full of potential?

- Craft goals – Goals should stem from the opportunities identified in the previous phase. These can be linked with results so progress can be monitored and evaluated. Use goal statements for more clarity.

- Create action plans – How will we work towards these goals? Action plans should enable implementation and there may be a specific plan for each goal.

Implemented properly with an engaged group of stakeholders, the SOAR framework ideally aims to encourage collective commitment to the shared vision that emerges (Stavros & Hinrichs, 2009).

The Appreciative Inquiry Summit

You’ll have noticed from the Appreciative Inquiry example above that large-scale meetings (or retreats, or similar) were mentioned pretty frequently. The described ‘large-scale retreats’ were Appreciative Inquiry Summits (AI Summits), which typically last a few days and bring together all relevant participants for the 4D initiative. In other words:

“a large group planning, designing, or implementation meeting that brings a whole system of internal and external stakeholder together in a concentrated way to work on a task of strategic, and especially creative, value.”

(Cooperrider, 2019)

Ludema and Mohr’s (2003) book of the same name covers the methodology in greater detail; the five parts look respectively at:

- Understanding the methodology, essential conditions, and what to expect from beginning to end;

- Sponsoring, planning, and creating an AI Summit;

- The 4-Ds during the Summit, and information for facilitators;

- Follow-up and a look at appreciative organizations; and

- An appendix with notes and a sample workbook.

You can get The Appreciative Inquiry Summit: A Practitioner’s Guide at Amazon.

75 PowerPoints on Appreciative Inquiry (PPT)

Here are some downloadable resources that could be useful if you are hoping to introduce the Appreciative Inquiry Model in your company.

- Appreciative Inquiry – Here is an Appreciative Inquiry PPT from the David L. Cooperrider Center for Appreciative Inquiry. It explains the evolutionary history of the approach and gives helpful comparisons with traditional problem-solving practices, then outlines the theoretical principles and some case studies.

- Building Our Most Desired Future: Appreciative Inquiry in the Workplace – This presentation comes from the University of Wisconsin and explains both AI theory and its practical applications, along with an overview of the 4D cycle of AI.

- World Appreciative Inquiry Conference 2012 Powerpoints – This is an entire collection of 72 presentations from WAIC 2012, and it is full of case studies about AI, how its practice can be promoted, and more.

6 TEDTalk and YouTube Videos

If you’re after a summary or discussion in video format, try one of these.

1. Introduction to Appreciative Inquiry and the Cooperrider Center at Champlain College SD

A quick background and discussion of the ‘why’ of AI, its benefits, and how it differs from conventional problem-focused approaches, by the Center’s Academic director Dr. Lindsay Godwin.

2. How to Do An Appreciative Inquiry Interview

Another video by Dr. Godwin that looks at how to start AI conversations.

3. Playful inquiry – Try this anywhere: Robyn Stratton-Berkessel at TEDxNavesink

Consultant and speaker Robyn Stratton-Berkessel talks about the creativity and engagement benefits of AI.

4. Appreciative Inquiry

If you prefer a good explainer video, this one gives a concise overview of ‘why we start with what’s already working’.

5. David Cooperrider Speaking on Appreciative Inquiry

David Cooperrider gives a little background on how AI started as he recounts his conversation with the late Peter Drucker.

6. Appreciative Inquiry – John Hayes

Management Professor John Hayes talks about the background of AI and gives examples of how it impacts engagement and motivation.

9 Quotes

We live in worlds our questions create.

David Cooperrider

The marvelous thing about a good question is that it shapes our identity as much by the asking as it does by the answering.

David Whyte

Appreciative Inquiry is based on a deceptively simple premise: organizations grow in the direction of what they repeatedly ask questions about and focus their attention on.

Gervase Bushe

Our worlds are formed by the questions we ask.

David Cooperrider

Problem talk creates problems – solution talk creates solutions.

Steve De Shazer

Studies of organizational excellence have shown that the art and science of asking powerful positive questions is much more important than looking for the gaps, weaknesses, and limitations in a system.

Anne Radford

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

Albert Einstein

You can tell whether a man is clever by his answers. You can tell whether a man is wise by his questions.

Naguib Mahfouz

No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.

Albert Einstein

A Take-Home Message

Appreciative Inquiry can pretty much be seen as a nexus of positive psychology and OD—both super-stimulating and rewarding areas for practitioners in either. If you find yourself nodding sagely along every time you hear “culture eats strategy for breakfast”, you’ll probably love the promise of AI.

In that case, I hope the resources in this article are helpful. I would love to hear your experiences of AI in practice, so please do share any of your thoughts with me in the comments.

If you’re interested to read more, be sure to check our other articles on Appreciative Inquiry or the following books on appreciative inquiry.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Strengths Exercises for free.

- Barrett, F. & Fry, R. (2005). Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Approach to Cooperative Capacity Building. Chagrin Falls, OH: Taos Institute Publishing.

- Basadur, M. (2004). Leading others to think innovatively together: Creative leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 103-121.

- Boyce, M. E. (2003). Organizational learning is essential to achieving and sustaining change in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 28(2), 119-136.

- Bright, D. S. (2009). Appreciative Inquiry and Positive Organizational Scholarship: A Philosophy of Practice for Turbulent Times. OD Practitioner, 41(3), 2-7.

- Bushe, G. (2013). Foundations of Appreciative Inquiry: History, Criticism, and Potential. AI Practitioner, 14(1), 8-20.

- Conklin, T. A., & Hartman, N. S.(2014). Appreciative Inquiry and Autonomy-Supportive Classes in Business Education: A Semilongitudinal Study of AI in the Classroom. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(3), 285-309.

- Cooperrider, D., & Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life. In Research in Organizational Change and Development (pp. 81-142). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (1999). A positive revolution in change: Appreciative Inquiry. In Holman, P., Devane, T. (Editors). Appreciative Inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Barrett-Koehler Communications, Inc.

- Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D. D., Stavros, J. M., & Stavros, J. (2008). The appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Davidcooperrider.com. (2011). Beyond Problem Solving to AI. Retrieved from http://www.davidcooperrider.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/BeyondProblemSolving-x.pdf

- Davidcooperrider.com. (2019). What is Appreciative Inquiry? Retrieved from http://www.davidcooperrider.com/ai-process/

- Drew, S. A., & Wallis, J. L. (2014). The use of Appreciative Inquiry in the Practices of Large-Scale Organisational Change a Review and Critique: A review and critique. Journal of General Management, 39(4), 3-26.

- Goleman, D. (1987). Research Affirms Power Of Positive Thinking. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/03/science/research-affirms-power-of-positive-thinking.html

- Grant, S., & Humphries, M. (2006). Critical evaluation of appreciative inquiry: Bridging an apparent paradox. Action Research, 4(4), 401-418.

- Hammond, S. A. (2013). The Thin Book of Appreciative Inquiry. Thin Book Publishing.

- Johnson, G., & Leavitt, W. (2001). Building on Success: Transforming Organizations through an Appreciative Inquiry. Public Personnel Management, 30(1), 129–136.

- Kessler, E. H. (Ed.). (2013). Encyclopedia of Management Theory. Sage Publications.

- Lines, R. (2004). Influence of participation in strategic change: resistance, organizational commitment and change goal achievement. Journal of Change Management, 4(3), 193-215.

- Linley, P. A., Nielsen, K. M., Wood, A. M., Gillett, R., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). Using signature strengths in pursuit of goals: Effects on goal progress, need satisfaction, and well-being, and implications for coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 5(1), 6-15.

- Ludema, J., & Mohr, B. (2003). The appreciative inquiry summit: A practitioner’s guide for leading large-group change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Ludema, J. D., Cooperrider, D. L., & Barrett, F. J. (2006). Appreciative inquiry: The power of the unconditional positive question. Handbook of Action Research, 155-165.

- Page, S., Burgess, J., Davies-Abbott, I., Roberts, D., & Molderson, J. (2016). Transgender, mental health, and older people: an appreciative approach towards working together. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(12), 903-911.

- Schooley, S. E. (2008). Appreciative democracy: the feasibility of using appreciative inquiry at the local government level by public administrators to increase citizen participation. Public Administration Quarterly, 243-281.

- Stavros, J., Cooperrider, D., & Kelley, D. L. (2003). Strategic inquiry appreciative intent: inspiration to SOAR, a new framework for strategic planning. AI Practitioner, 1(4), 10-17.

- Stavros, J., & Hinrichs, G. (2009). Thin Book of SOAR: Building Strengths-Based Strategy. Thin Book Publishing Co.

- Stavros, J. & Torres, C. (2005). Dynamic Relationships: Unleashing the Power of Appreciative Inquiry in Daily Living. Chagrin Falls, OH: Taos Institute Publishing.

- Stratton-Berkeessel, R. & Myers, T. (2019). Synchronicity: An Exciting Emergent Principle in Appreciative Inquiry. Retrieved from https://appreciativeinquiry.champlain.edu/educational-material/synchronicity-exciting-emergent-principle-appreciative-inquiry/

- Taylor, F. W. (1919). The Principles of Scientific Management. New York & London: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

- Whitney, D. & Trosten-Bloom, A. (2003). The Power of Appreciative Inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Very succinct discussion on the topic Catherine! Thumb up for you!